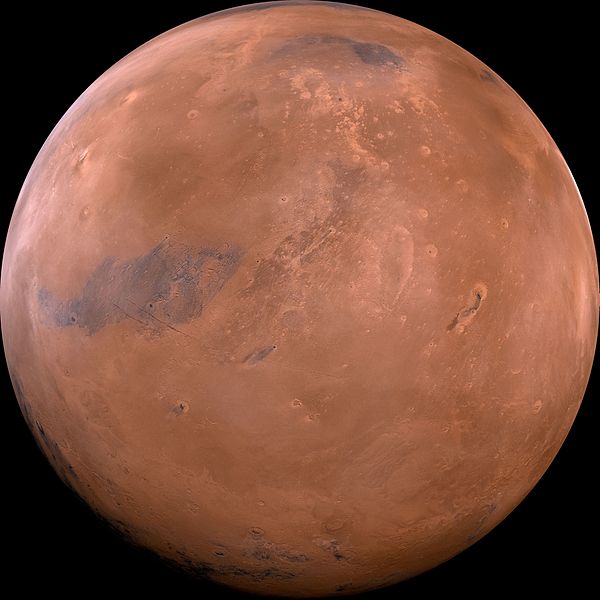

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

But, first, some additional items for your rapidly-growing “Religion Poisons Everything” file:

USA Today: “Faith groups provide the bulk of disaster recovery, in coordination with FEMA”

“Church Offering Relief to Tens of Thousands of Flood-Weary Peruvians” (from way back on 3 April 2017)

“Church Offering Relief, Support in Aftermath of Deadly Quake in Southern Mexico”

“Church work parties pour into flooded Texas neighborhoods”

“President Eyring lifts spirits in Irma-weary Puerto Rico”

From the LDS Newsroom: “Hurricane Irma Updates”

However, if, even after these stories and many more like them, you remain undisgusted by the evils of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, here’s how you can donate to LDS Humanitarian Services:

***

In June 1863, the passenger ship Amazon set sail from London for America with nearly 900 Latter-day Saint emigrants aboard. However, just before she weighed anchor, many Londoners—including both government officials and clergymen—came to take a look at the Mormons, up close and at first hand, as well as at their traveling arrangements. One of these visitors Charles Dickens, the famous author of such works, by that time, as The Pickwick Papers (1837), Oliver Twist (1839), Nicholas Nickleby (1839), The Old Curiosity Shop (1841), Barnaby Rudge (1841), A Christmas Carol (1849), Martin Chuzzlewit (1844), Dombey and Son (1848), David Copperfield (1850), Bleak House (1853), Hard Times (1854), Little Dorrit (1857), A Tale of Two Cities (1859), and Great Expectations (1861). He is generally regarded as the greatest novelist of Victorian England.

Dickens spent several hours on board the Amazon, quietly observing the Saints on the ship and interviewing George Q. Cannon, a member of the Twelve who was serving at the time as the president of the British Mission. (Elder Cannon would go on to serve as a counselor in the First Presidency to Brigham Young, John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and Lorenzo Snow.)

A month or so after his visit to the Amazon, Dickens published an account of it in an essay for the periodical All the Year Round (4 July 1863), titled “The Uncommercial Traveller.” In his essay, he remarked that virtually all of the emigrating Latter-day Saints were tradesmen and craftsmen and their families, people of the working class. He was worried about what these British converts to Mormonism might encounter when they actually arrived in Utah. (He was surely familiar with the horror stories going around England at the time – which would continue for the next several generations — about the theocratic “Mormon kingdom” in the remote North American west.) But he was deeply impressed by what he had actually seen. The emigration was thoroughly well-organized, calm, orderly.

“I went on board their ship,” he wrote, “to bear testimony against them if they deserved it, as I fully believed they would; to my great astonishment they did not deserve it; and my predispositions and tendencies must not affect me as an honest witness. I went over the Amazon’s side feeling it impossible to deny that, so far, some remarkable influence had produced a remarkable result, which better known influences have often missed.” Of the Saints themselves, Dickens confessed that, had he not known they were Mormons, he would have described them as, “in their degree, the pick and flower of England.”