Today, of course, is the sixteenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks that killed 2,996 people, injured more than 6,000 others, caused over $10 billion in damage, and fundamentally changed world history.

Some of you may be unaware that, for the tenth anniversary back in 2011, President Thomas S. Monson of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints wrote a reflective piece about the lessons of 9/11 for the Washington Post:

“9/11 destruction allowed us to spiritually rebuild”

***

Many things can and should be said about that terrible day. And I don’t want to minimize in any way the satanic evil of those who perpetrated the attacks, nor to downplay the dysfunctionality in parts of the worldwide Islamic community that seemed, in their eyes, to give them license, endorsement, and support for what they did.

I think it worthwhile, however, to call attention to this website, maintained by Professor Charles Kurzman of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill:

“Islamic Statements Against Terrorism”

Here’s a short column about Professor Kurzman’s important publications:

“Why are there so few Muslim terrorists?”

***

A statement from Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya:

“Islam is a mercy. If you see its opposite, cruelty, then know that is not Islam.”

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad b. Abī Bakr b. Ayyūb al-Zurʿī al-Dimashqī al-Ḥanbalī (1292–1350 AD) is commonly known as “Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya” (“the son of the principal of [the school of] Jawziyyah”) or, for short, as “Ibn al-Qayyim” (“son of the principal”; ابن قيم الجوزية). Sometimes, reverentially, he’s referred to as “Imam Ibn al-Qayyim” in the Sunni Muslim tradition.

He was an important medieval Islamic jurisconsult, theologian, and spiritual writer who belonged to the Hanbali school of orthodox Sunni jurisprudence.

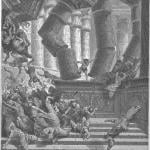

Historically, he’s closely associated with the influential (and controversial) fourteenth-century Sunni reformer Taqī ad-Dīn Ahmad b. Taymiyya (تقي الدين أحمد ابن تيمية). He was a student of Ibn Taymiyya’s and, arguably, his foremost disciple. When Ibn Taymiyya was jailed in the Citadel of Damascus in 1326 for his dissenting opinions, which clashed with and rejected portions of established Islamic tradition, Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya was imprisoned with him.

This is significant, because Ibn Taymiyya was, arguably, a very conservative Muslim thinker. He was a rather marginal figure in his own time and in the centuries that immediately followed, but he has become one of the most influential medieval writers in contemporary Islam. His Qur’anic interpretations and his views on the sunna of Muhammad — the Prophet’s biography seen as a basis for legal, ethical, and theological reflection — coupled with his willingness to reject certain aspects of the classical Islamic tradition, have resonated with today’s fundamentalist Islamic thinkers. Arguably, he has had considerable influence on contemporary “Salafism” and on modern jihadis. It’s pretty clear, for instance, that elements of his teachings had a profound effect on Muhammad b. Abd al-Wahhab, the eighteenth-century founder of the Hanbali reform movement that is followed in Saudi Arabia under the name of “Wahhabism.” Moreover, al-Qa‘ida and other jihadi groups have drawn support for much of their violence from the controversial fatwa written by Ibn Taymiyya that declared jihad against other Muslims legally permissible.

But would Ibn Taymiyya have wanted to claim the so-called “Islamic State” and al-Qa‘ida as his legitimate offspring today? I have genuine doubts on that score.

And his prominent disciple’s statement that “Islam is a mercy” and that mercy’s opposite, cruelty, “is not Islam” suggests that Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya might not have approved of them, either.