I’d never actually looked for it but, still, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that a personal, autobiographical essay that I published all the way back in 1996, in Susan Easton Black, ed., Expressions of Faith: Testimonies of Latter-day Saint Scholars, is available online:

“Shall We Not Go On in So Great a Cause?”

***

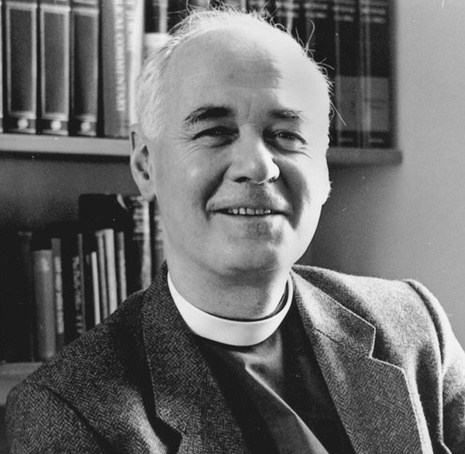

John Charlton Polkinghorne, KBE (Knight of the British Empire), FRS (Fellow of the Royal Society), is an English theoretical physicist, theologian, writer, and Anglican priest. He was a professor of mathematical physics at the University of Cambridge until he resigned his professorial chair to study for the priesthood, becoming an ordained Anglican priest in 1982. He served as the president of Queens’ College, Cambridge, from 1988 until 1996.

Here’s a comment from him that I found noteworthy:

“Science has purchased its very great success by the modesty of its ambition. Science does not seek to ask and answer every sort of question. It restricts itself essentially to asking questions of process, which are ‘how questions’ of how things come to be. It also restricts the kind of experience that it takes into account in framing and finding its answers to those questions.”

(Sir John Polkinghorne, “Belief in God in an Age of Science,” in Eric Metaxas, ed., Life, God, and Other Small Topics [New York: Plume/Penguin, 2011, 9])

Sir John’s point is an extremely important one. It expresses one of the reasons why I’m quite unimpressed with people who like to contrast the successes of science with what they see as the lack of such successes in the world of religion.

Tape measures have a very successful record in measuring table tops, bedsteads, driveways, growing children, and women being fitted for dresses.

Literary criticism and philosophical discussions come nowhere near the record of objective success and clarity achieved by tape measures.

Does that demonstrate, though, that tape measures are more valuable and important than performances of Shakespeare, readings of Molière and Goethe and Dante, or discussions of the good, the true, and the beautiful?

No, it simply means that tape measures have been developed (very well) to deal with a severely restricted and well defined sector of the world. Applying a tape measure to a performance of Hamlet, though, or using it to evaluate Goethe’s Faust or Dante’s Paradiso, or to resolve an ethical dilemma, or the judge between Mozart’s “Jupiter Symphony” and “Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity” from Gustav Holst’s orchestral suite The Planets would be . . . Well, it would be more than slightly mad.

David Aberg’s painting Mother Earth, located in Angelholm, Sweden, measures 86,000 square feet. By contrast, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa measures only about thirty inches by twenty-one inches. However, only a loon would pronounce Mother Earth a greater painting than the Mona Lisa on the grounds that it’s demonstrably much, much larger, or because it’s composed of quantifiably more daubs of paint.