An autobiographical reflection:

I came to Brigham Young University as a freshman mathematics major. I had a virtually life-size poster of Albert Einstein on the wall in my dorm room. My real fascination, however, was with cosmology — the very biggest of big subjects. I was interested in the origins and the nature of the cosmos as a totality. And in its structure.

I soon realized, though, that mathematics wasn’t really my passion, as it was for some of my fellow students. I also recognized that it wasn’t my forte, and that I would be unlikely to be able to achieve things at a level in the field that would satisfy me.

In the meantime, as I’ve mentioned before, I had a dorm neighbor and good friend who was taking a class in Greek.

I had come under the sway of the writings of Hugh Nibley some time before, and the idea of studying Greek — and antiquity more generally — fascinated me. So I changed my major to Greek, with a minor in philosophy. (No philosophy major was available at BYU at the time.)

I’m sure that my parents were dismayed, wondering how on earth I would ever be able to make a living with either Greek or philosophy. It’s a good question, of course, and they would have been right to worry. But my mother, at least, always assumed that I would become a corporate lawyer, or something of that sort. (She and my Dad even brought the subject up after I had been hired on the faculty of BYU, offering to pay my tuition for law school if I ever wanted to go that direction.)

Corporate law had absolutely no appeal to me, however. Still, I might have gone more or less that way, at one point. Legal issues interest me. Politics and political philosophy interest me very much. But, had I gone into law, I probably would have ended up not as a highly paid corporate lawyer but as a professor at a law school, teaching jurisprudence or legal history or the philosophy of law. I’m an academic by temperament, not a practical man of action.

Anyway, once I finished my oh-so-marketable degree in Greek and philosophy, I abandoned Greek to study Arabic, Persian, and Islam.

But the abandonment wasn’t quite as complete as it might seem at first glance. After years of study in Jerusalem and Cairo, I did my Ph.D. at the University of California at Los Angeles, which has an exceptionally strong program in Near Eastern studies and which had, for me as a native of California, the very pleasant advantage of being cheap — especially with the fellowship that I won. My dissertation concentrated on the cosmology [!] of an early eleventh-century Muslim Neoplatonist by the name of Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani. And it devoted a great deal of attention to comparing his thought not only with that of his Muslim contemporary Avicenna (Ibn Sina) and his Isma‘ili Shi‘i predecessor Abu Ya‘qub al-Sijistani but with the work of the late Greek thinkers Iamblichus and Proclus and, especially, with the Enneads of the great Plotinus, the third-century founder of Neoplatonism.

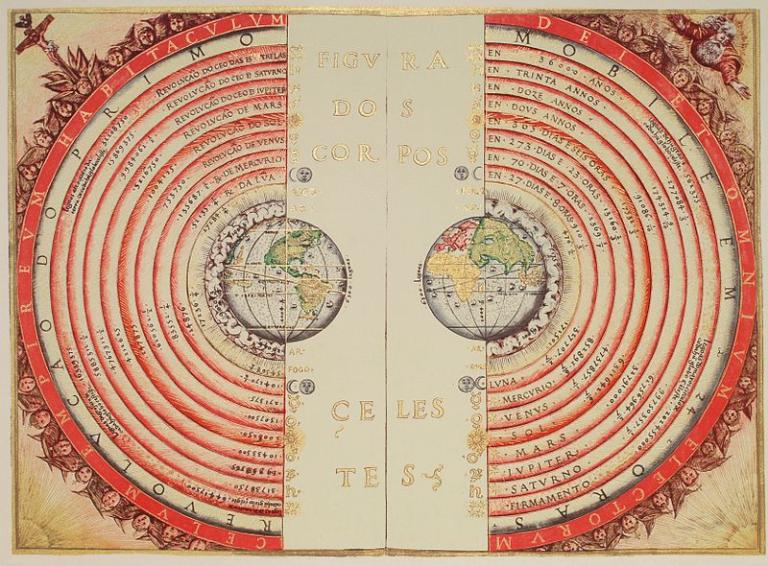

So my Greek training and my philosophical interests persisted through all the changes. And, as I look back, I realize that that early interest in cosmology did, as well. Moreover, it continues. Eventually, I intend to publish at least one very accessible book (and one not-so-accessible book) that will reflect my ongoing fascination with models of the cosmos.

The child, as Wordsworth put it, is father to the man.