(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

At their request, we met with several of our group who were not otherwise obligated and took them over to al-haram al-sharif, the “Temple Mount,” where the line to get up onto the Mount was the longest I’ve ever seen it — extending out the Dung Gate and even somewhat down the hill. Fortunately, though, when it moved, it moved fairly quickly.

So we took them up past Al-Aqsa Mosque, past what I believe is the largest of the outdoor ablution fountains on the Mount, over to the Dome of the Rock, down to the Golden Gate, and out of the Temple Mount area via Al-Ghazali Square.

I spoke to them about the history of the site — though very sparingly of its biblical associations, owing to sensibilities among the Palestinian guards there — and most particularly about its connection with the story of the mi‘raj of Muhammad.

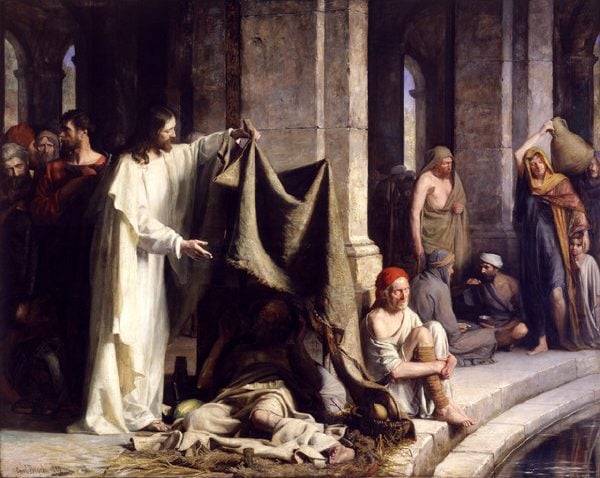

Once we were off the Temple Mount, we visited the Church of St. Anne — a traditional site associated with the birth and childhood of the Virgin Mary — and the Pool of Bethesda, which is directly adjacent to it. We sang “As I Have Loved You” in the church, which has marvelous acoustics. We were a small group, but I don’t think we were too bad.

St. Anne (think of such places at Santa Ana, California) and St. Joachim (think of such places as San Joaquin, California) were, according to quite old traditions, the parents of the Virgin. There is another tradition, though, that places her childhood in Sepphoris, very near to Nazareth.

The Pool of Bethesda is interesting for a number of reasons. For one thing, it’s located so far below the modern street level. That gives me a chance to speak about how ancient cities tend to grow upward and upward. And it’s a jumble of architectural style and archaeological layers, extending from roughly the eighth century before Christ through the time of the New Testament, and then through Hadrian’s Temple of Asclepius and Serapis — Asclepius was a Roman demigod of healing — and a Crusader church.

Another reason that the Pool of Bethesda interests me is that, as I understand it, one of the arguments against the historicity of the gospel of John centered on the account given at John 5 of Christ’s miracle of healing there. There was, some apparently argued, no such place. This site was discovered in the nineteenth century, however, beneath centuries of detritus and rubble, covered over by buildings, and long dry. But it’s there. And the Johannine account became much more credible.

Posted from Jerusalem, Israel