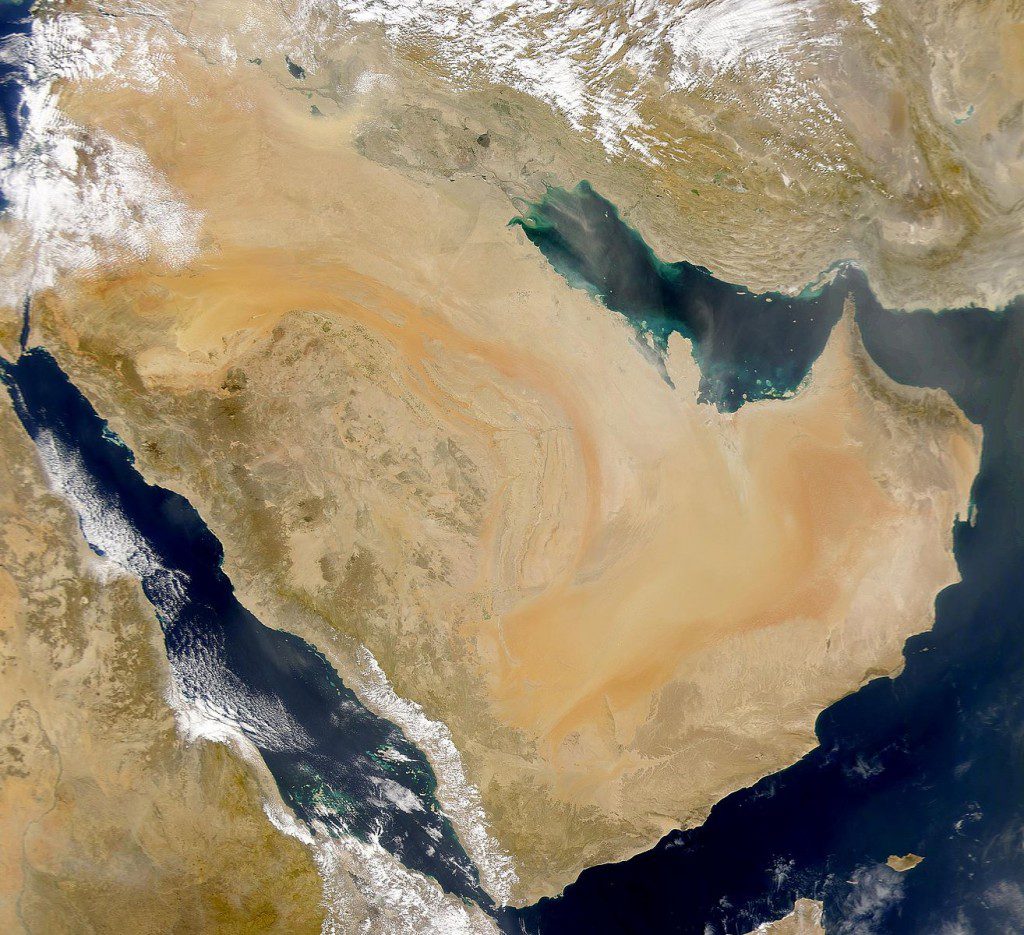

(NASA photograph; public domain)

In my manuscript, I’ve just spoken about the pre-Islamic Arabian value of revenge, rather than charitable forgiveness. So we continue:

The story of Shanfara, a poet and outlaw of the tribe of Azd, will also illustrate something of the ideal Arabian hero. The story is told that when he was just a young child, he was kidnapped by another tribe, known as the Banu Salaman. (Banu, here, means “sons [of].”) He was brought up among them and for many years had no idea that he was not actually one of them. However, when he grew up and learned the truth he vowed that he would avenge the injury done to him and his tribe by killing a hundred warriors of the Banu Salaman. Preparing his revenge, he left the Banu Salaman and went back to his real kinfolk, the Banu Azd. Over the next several years, he did indeed manage to kill ninety-eight of the Banu Salaman, but then they contrived to ambush him, and it looked as if he would fail to fulfill his vow. However, when, in the fierce fight of the ambush, one of his hands was chopped off by the stroke of a sword. Shanfara grabbed the amputated hand with his other and threw it as hard as he could in the face of one of his attackers, killing him. Furious, the ambushers then overpowered Shanfara and hacked him to death, leaving his body to rot on the desert sand. The total of the Banu Salaman that he’d slain came to ninety-nine, one short of fulfilling his vow. He’d failed, or so one might have thought. However, many days after Shanfara’s death, one of the Banu Salaman was passing by and paused to look at the bones of their late enemy as they lay there, bleaching in the intense desert sun. To show his contempt, the man gave a powerful kick to Shanfara’s skull, sending it bouncing across the sand. But a splinter of bone from the skull pierced his foot. The wound festered, and the man died. Shanfara, in other words, had fulfilled his vow. And his persistence in revenge—a persistence that endured beyond his death—makes him a great hero of pre-Islamic Arabia.

Honor was another pre-Islamic Arabian virtue. A couple of stories will illustrate something of what it meant to the early inhabitants of the Peninsula.

The first, and the shortest, is connected with a famous pre-Islamic poet by the name of Tarafa. Tarafa had a problem—and perhaps not an unexpected one, considering that he made his living by words. He couldn’t keep his mouth shut. Specifically, he showed great impertinence toward Amr ibn Hind, who reigned as king of Hira between 554 and 568 A.D. On one occasion, for instance, finding himself seated opposite the king’s beautiful sister at a banquet, he exclaimed:

Behold, she has come back to me,

My fair gazelle whose ear-rings shine;

Had not the king been sitting here,

I would have pressed her lips to mine!

This wasn’t the kind of outburst that was likely to win favor with the princess’s royal brother. But the impertinence was nothing compared to the insult that Tarafa had earlier directed at the king himself:

Would that we had instead of Amr

A milch-ewe bleating round our tent!

Fed up with such behavior from a mere poet, Amr sent Tarafa and a friend (who must have been similarly offensive) to Bahrayn, carrying sealed letters to that island’s governor. En route, however, the friend began to grow suspicious and opened his letter. Sure enough, he found that it contained orders to bury him alive. He threw his letter into the stream and advised Tarafa to do likewise. Tarafa, however, refused. He felt himself honor-bound to carry his letter to Bahrayn and to deliver it unopened, as he had promised to do. When he arrived in Bahrayn, he was executed. According to some sources, he wasn’t yet twenty years old.

The next story relates to the pre-Islamic Arabian Jew Samawal, whom we’ve already briefly met. He lived in a castle some distance to the north of an oasis called Yathrib, a place that will take on considerable importance in the next chapter. One day, the great pre-Islamic poet Imru al-Qays is said to have taken refuge with Samawal when fleeing from some of his enemies (of whom he had many) in the direction of Syria. Before the poet departed from the castle, he left five coats of mail armor with Samawal for safe-keeping, items that had been handed down from generation to generation as heirlooms within his family. Imru al-Qays then continued on his journey toward Syria. Eventually, he went on to Constantinople, where he sought help from the Byzantine emperor in regaining his kingdom, which had been stolen from him. The appeal found sympathy, but Imru al-Qays died on his way home.

Meanwhile, though, his enemy, the king of Hira, sent an army against Samawal, demanding the five coats of mail that Imru al-Qays had deposited with him. But Samawal had given a solemn promise to take care of the armor, and he refused to yield it up. So the army of Hira besieged his castle. The siege went on and on, and Samawal was unbending. Finally, the besiegers were able to capture Samawal’s son, who had gone out to hunt.

“Do you know this boy?” the commander of the besieging forces asked.

“Yes,” replied Samawal. “He is my son.”

“Then will you deliver up the things you have in your possession, or should I kill him?”

“Do with him as you will,” replied Samawal. “I will never break my oath, nor will I give up the property of my guest.”

The general then drew his sword and hacked the boy to death before the eyes of his father, Samawal. Immediately afterwards, the army of Hira raised the siege and went home, knowing now that Samawal would never yield up what they wanted.