Yet more from my notes:

The late Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002), Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology at Harvard University and an enormously popular popularizer of evolutionary biology, though himself an agnostic (and a Marxist), passionately denied that evolutionary theory was necessarily atheistic, invoking the memory of his third-grade teacher, Mrs, McInerney, whose practice it was to rap the knuckles of pupils who said or did things that she regarded as especially stupid:

To say it for all my colleagues and for the umpteenth million time (from college bull sessions to learned treatises): science simply cannot (by its legitmate methods) adjudicate the issue of God’s possible superintendence of nature. We neither affirm nor deny it; we simply can’t comment on it as scientists. If some of our crowd have made untoward statements claiming that Darwinism disproves God, then will find Mrs. McInerney and have their knuckles rapped for it (as long as she can equally treat those members of our crowd who have argued that Darwinism must be God’s method of action).

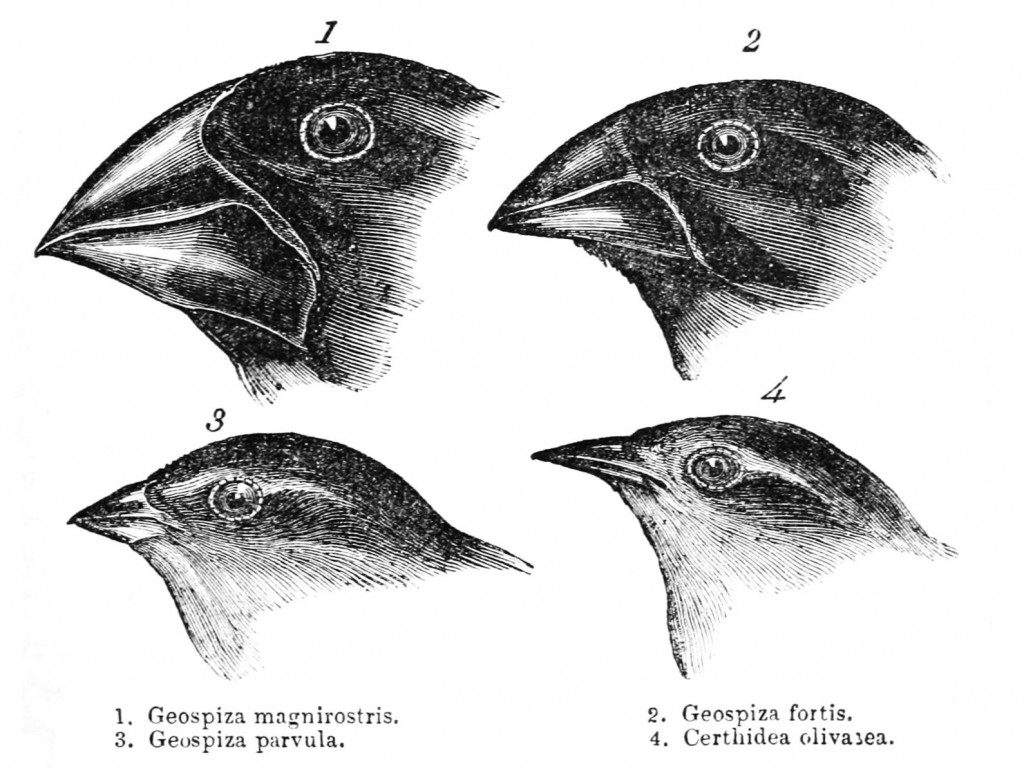

Charles D. Wolcott, who discovered the Burgess Shale fossil about which I shall have more to say later, was both a devout Darwinian and a believing Christian who was convinced that God had used evolution to effect his divine purposes. And, since Walcott, the “two greatest evolutionists of our generation,” as Gould termed them, took different sides of the debate over the existence of God: George Gaylord Simpson was, it is true, an agnostic, but Theodosius Dobzhansky was devoutly Russian Orthodox. “Either half my colleagues are enormously stupid,” concluded Gould, “or else the science of Darwinism is fully compatible with conventional religious beliefs—and equally compatible with atheism.”[1]

It is striking that two substantial surveys of the religious beliefs of practicing scientists, one carried out early in the twentieth century (in 1916) and the other conducted near that century’s end (in 1996), show virtually no difference in the proportion of scientists who held to some form or another of personal religious belief. Roughly 40% of the scientists professed such faith in both surveys, as opposed to 40% who might be described as atheistic and 20% who could be termed undecided or agnostic. The vast advances of science and technology during the eighty years intervening between the two surveys—which included such landmarks as the discovery of the expanding universe and its likely beginning in the Big Bang, the deciphering of the structure of DNA, the rise to dominance of both relativity and quantum theory, and the invention of such fields as neurophysiology—appear to have had no impact on religious beliefs among professional scientists. If the march of science inevitably destroys faith, scientists themselves seem unaware of that fact.[2]

[1] Cited by McGrath. Find original: Stephen Jay Gould, “Impeaching a Self-Appointed Judge,” Scientific American 267/1 (1992): 118-121. Comment on this review’s treatment of Philip Johnson.

[2] See Alister McGrath, The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World (New York and London: Doubleday, 2004), 110-111.