A final reminder:

I’ll be speaking tomorrow at 10 AM as part of the annual symposium on “Reason for Hope: Responding to a Secular World” sponsored by BYU’s Wheatley Institution. You can find details about the conference at

***

(NASA public domain photograph)

A paraphrase of Richard Panek, The 4% Universe: Dark Matter, Dark Energy, and the Race to Discover the Rest of Reality (Boston and New York: Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), 59-61:

Here’s the problem: Premise One, the universe is full of matter. Premise Two, matter attracts other matter by means of gravity. Conclusion: The universe must be collapsing. But it evidently isn’t. So why not?

The problem has been around for a long time. The clergyman Richard Bentley confronted Sir Isaac Newton with it in 1692, not long after the first publication of Newton’s Principia. And Newton acknowledged that it was a striking question.

His argument, he replied, required “that all the particles in an infinite space should be so accurately poised one among another as to stand still in a perfect equilibrium.” A remarkable thing, he knew: “For I reckon this as hard as to make not one needle only but an infinite number of them (so many as there are particles in an infinite space) stand accurately poised upon their points.”

But how could such remarkable equilibrium be possible? A subsequent edition of the Principia, responding to Rev. Bentley’s objection, included a “General Scholium” that postulated Newton’s sincere and characteristically devout Christian answer: It was divine providence. “And so that the systems of the fixed stars will not fall upon one another as a result of their gravity, he has placed them at immense distances from one another.”

But “immense distances” don’t actually resolve the problem. The force of gravity would be greatly attenuated over such distances, yes, but it would still be there. And, of course, postulating God as the explanation didn’t fit the emerging “methodological naturalism” of Western science, of which Newton was a principal founder.

Moreover, over the next generations astronomers began to realize that the so-called “fixed stars” aren’t fixed at all. They’re in constant motion relative to one another. So the idea that they were in perfect equilibrium became untenable.

How to deal with this problem?

In his 1917 paper “Cosmological Considerations on the General Theory of Relativity,” Albert Einstein inserted a “fudge factor” into his equation that he called lambda. It was intended to represent whatever it was — “at present unknown” — that was somehow keeping the universe from collapsing upon itself. Rather like Newton’s approach to gravity itself — mathematically describing its effects but providing no account of its intrinsic nature — Einstein offered no proposal or hypothesis for what lambda might actually be.

Then came Edwin Hubble’s epochal 1923 discovery of evidence suggesting that the universe isn’t static at all. But it isn’t contracting, either. It’s expanding.

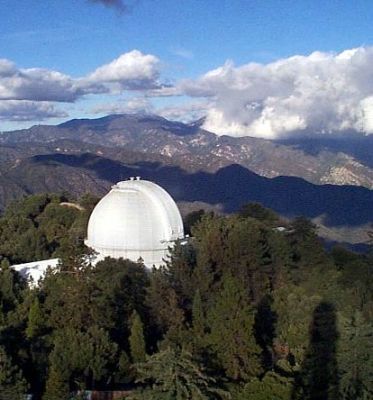

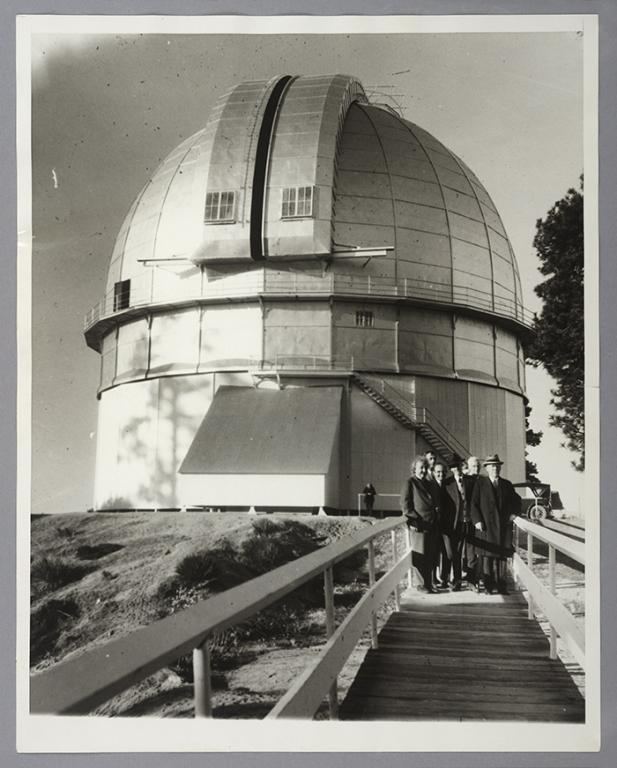

In 1931, Einstein traveled from Germany to the 100-inch telescope of Mount Wilson Observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains, located to the northeast of Pasadena, where Hubble had made his discovery. After visiting with Hubble and reviewing the data, he discarded lambda. The assumption of a static universe had been, simply, false.

A personal addendum: I saw Mount Wilson virtually every day of my life, growing up essentially at its foot in San Gabriel, California. Its broadcasting towers and some of its observatories are easily visible from the valley below. I myself visited it multiple times — with my family, on school field trips, and even with a couple of girlfriends (on separate occasions!). It was many years before I grasped the world-historical scientific significance of the place. To me as a school kid, it was just a chance to get out of classes.