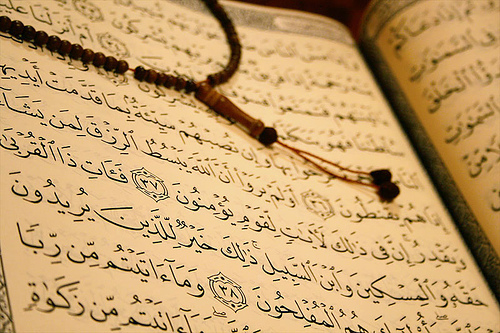

Wikimedia Commons public domain

Continuing with a manuscript on which I’m working:

Muslims believe that the Qur’an as they have it today is an actual transcript from a heavenly volume known as the “Preserved Tablet,” or the “Mother of the Book.”[1] They believe that Muhammad did not write it and that it contains no admixture of his own personality or individual idiosyncrasies. He was merely the pipeline, as it were, the conduit through whom God’s revelation came. Given such an understanding, we are not surprised to learn that, for virtually all Muslims, the Qur’an is considered flawless. It is the actual, literal word of God. There can be no possibility of error in it.[2] It contains the whole and absolute truth about God and about what mankind must do to be saved.

Holding this high view of their scripture, Muslims see even the physical book itself as holy, for it holds the word of God. (One of my copies of the Qur’an, which I had bound in leather while I was living in Cairo, bears on its spine the Arabic inscription, “Let none touch it but the pure.”) Many Muslims are horrified, therefore, when they see a Latter-day Saint sit down in a classroom and place the Bible or the Book of Mormon on the floor under his chair. If Mormons really took their scriptures to be what they claim them to be, these observers reason, they would not treat them with such disrespect.

The Qur’an is Muhammad’s miracle, the major proof of his prophethood. Its creation was utterly beyond his human ability. For devout Muslims, the sacred book is pure beauty. It is art—although not only art, and certainly not “art for art’s sake.” Quotations from it are engraved on plates, carved into the walls of buildings, lovingly inscribed on parchment in elaborate and beautiful calligraphy. Muslims love to hear the Qur’an chanted, and it moves them deeply. Qur’anic recitation begins and ends the broadcast day on Arabic television and radio and forms a major element of Muslim funerals. There are complex rules for such recitation, and those whose mastery of the rules and whose native talent make them exceptional reciters actually become popular “stars” in Islamic society. But the Qur’an is also ritual. It is the substance of prayer, and its verses are recited by ordinary people at every important moment of their lives.

[1] 43:1-3; 85:22; 3:7; 13:39; 43:4. The idea of a celestial record, containing information on both past and future, is a very ancient Near Eastern notion and is probably reflected in the book that Lehi saw (1 Nephi 1:8-15) as well as in the books seen by John the Revelator in his visions (Revelation 5:1-4: 20:12; compare Malachi 3:16). The ninety-seventh sura of the Qur’an declares that the book was revealed on the “Night of Qadr,” which resembles ancient (Babylonian) ideas of a night on which the gods came down to the lowest heaven and disclosed their will and the events of the coming year to specially selected listeners. Later Muslim theologians, believing that God is unchanging and that his speech must therefore be similarly eternal and unchanging, argued that the Qur’an is uncreated and co-existent with God himself.

[2] 39:28.