Sir John Polkinghorne, KBE (Knight of the British Empire), FRS (Fellow of the Royal Society), was a professor of mathematical physics at the University of Cambridge until he resigned his professorial chair to study for the priesthood, becoming an ordained Anglican priest in 1982. Thereupon, he served as the president of Queens’ College, Cambridge, from 1988 until 1996.

The following notes are drawn from his 1996 Terry Lectures, delivered at Yale University and published as John Polkinghorne, Belief in God in an Age of Science (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1998):

Polkinghorne says that the conversation between science and theology has been particularly active since roughly 1966, the year in which Ian Barbour’s important book Issues in Science and Religion was published. (Barbour held not only a Ph.D. in physics from the University of Chicago but a B.Div. from Yale Divinity School.) Another important book, in his judgment, was Arthur Peacock’s Creation and the World of Science, which appeared in 1979. (Arthur Peacocke, D.Phil., D.Sc., D.D., was University Lecturer in Biochemistry at the University of Oxford.)

And anyway, says Polkinghorne, the old myth of fierce warfare between science and religion has long since been revealed as a caricature.

Only in the media, and in popular and polemical scientific writing, does there persist the myth of the light of pure scientific truth confronting the darkness of obscurantist religious error. Indeed, when one reads writers like Richard Dawkins or Daniel Dennett, once sees that nowadays the danger of a facile triumphalism is very much a problem for the secular academy rather than the Christian Church. (77)

At the moment the biological world, particularly in its members who work with molecules rather than organisms displays notable hostility to religion, at least in the writings offered to the general educated public. (It is a curious cultural fact about our society that, though it would be considered improper for a believing scientist to exhibit that belief explicitly when writing for the lay public about science itself — as opposed to writing books explicitly about science and religion — it is apparently perfectly all right for the atheist to press unbelief in a similar scientific context.) (78-79)

***

And, while we’re at it, here is some news from the world of science:

“Distant Galaxies Challenge Our Understanding of Star Formation”

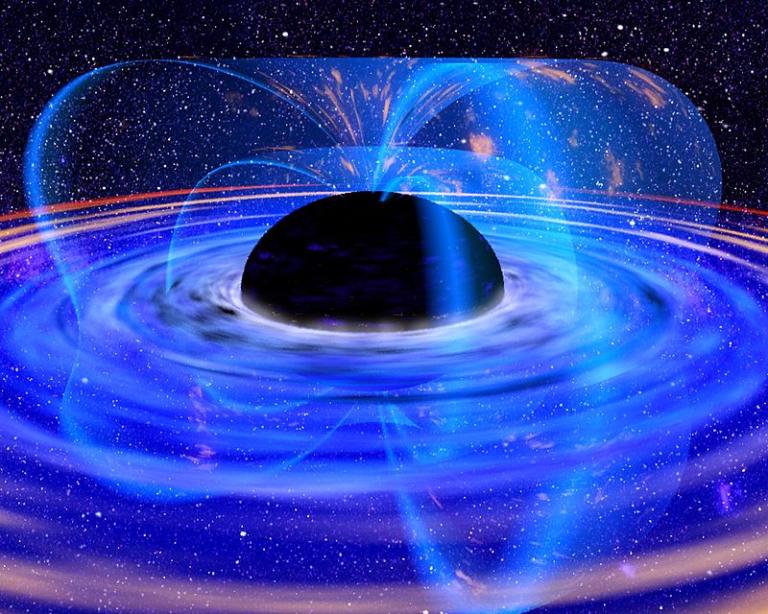

“What Would You See As You Fell Into a Black Hole?”

“Neutron anomaly might point to dark matter”

“Test of Einstein’s Theory Confirms the Sun Is Losing Mass”