Day after day after plodding day, we move forward:

Over the course of many years, students of the traditions about Muhammad and his companions worked out a complex and sophisticated system for testing and classifying hadith. Some hadith reports were ranked as sahih, or “sound,” which is to say that all of the links in their isnads, their chains of transmission, were good ones going back directly to the purported source of the tradition, who was usually the Prophet himself.[1] A slightly less reliable group of traditions were determined to be hasan, “good.” These “good” traditions had a weak link in their chain of transmission—someone whose integrity was questionable or whose contact with another transmitter was subject to doubt—but they were nevertheless acceptable if they were really needed because there was some outside corroboration that led scholars to think they were most likely true. Finally, and acceptable for very little, were those hadith reports that were judged to be da’if, or “weak.”[2] They would be used only when a judge or a theologian was desperate, and they would not be convincing to many.

A mastery of the thousands of hadith circulating in the Islamic world was what constituted ‘ilm, or “knowledge,” and those who had such knowledge were the “knowers” (ulama) par excellence.[3] Eventually, the ulama came to be a kind of rabbi class, the nearest thing that Islam has to a clergy. Authority did not proceed from ordination or priesthood, but from knowledge of the law.

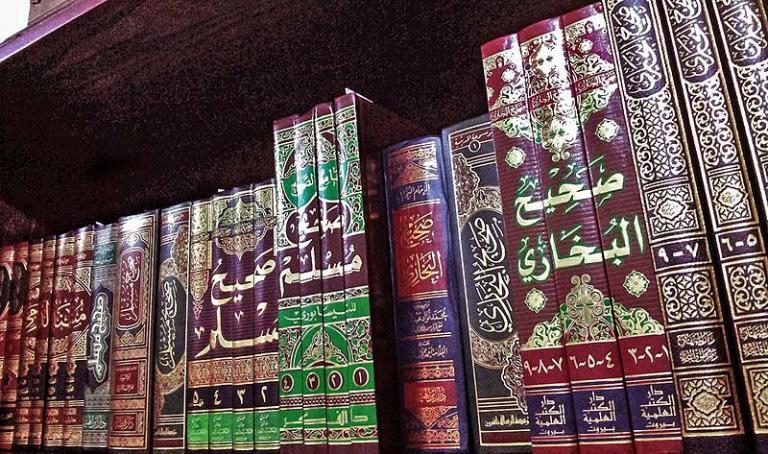

Finally, after the process of seeking out and sifting hadith reports for many decades, the time came for gathering the ones that had been adjudged to be reliable into accessible works of reference. The need was especially pressing in the law courts of the empire. It is to this that we owe the great collections of “sound” hadith which have taken on almost scriptural status in Sunni Islam. Foremost among these are two multivolume works, each entitled al-Sahih, compiled by al-Bukhari (d. 870) and Muslim (d. 875). As these and other manuals of hadith won acceptance, it was a knowledge of them—extending to memorization—that came to constitute real ‘ilm and would win an aspiring young scholar a place among the ulama.

[1] The Arabic word sahih is pronounced “sa-HEEH”—with the final “h” being sounded as if it began a syllable.

[2] Da’if is pronounced “da-EEF.”

[3] This word, which is spelled in a wide variety of ways by Western scholars, is pronounced roughly “oo-la-MAA.”