Continuing with my introduction to Islam for Latter-day Saints:

This focus upon submission to the inscrutable will of God as the characteristic mark of true religion points to Islam’s emphasis upon the omnipotence of God. It is an emphasis that is absolutely fundamental to the religion. It underlies Muslim rejection of the doctrine of the atonement of Christ and flavors daily life and speech throughout the Islamic world. To elaborate, God forgives whomever He chooses to forgive, and denies forgiveness to anybody he wants, for any reason he chooses. God is an absolute sovereign. There is no law to which he is subject, nobody to whom he must give an account. All creatures, all planets, all people, all prophets (including Jesus of Nazareth), all natural laws and moral principles are, in the Islamic view, equally powerless before the Lord of the universe.[1]

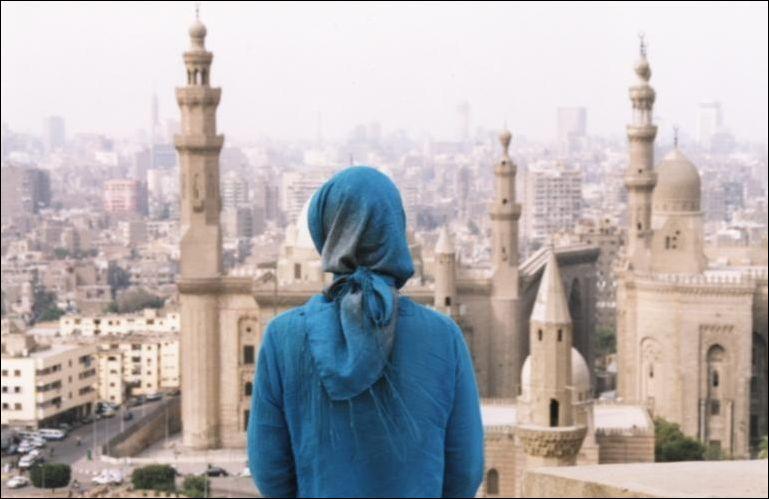

Muslims would strenuously reject the view, often heard in Mormon circles, that the atoning sacrifice of Christ was necessary in order to satisfy the demands of cosmic law, and that it was only then that God could extend forgiveness without upsetting the universal balance of things. (This view is prominent in the Book of Mormon. “What,” asked Alma the Younger of his son Corianton, “do ye suppose that mercy can rob justice? I say unto you, Nay; not one whit. If so, God would cease to be God.”)[2] They would want to know who would depose God, why he would “cease to be God.” Actions are right, in the standard Muslim view, because God says they are; he does not say they are right because of some celestial standard, independent of him and, in a sense, prior to him that tells him to do so. Thus, as a chemistry professor at the University of Cairo once told me, “God doesn’t need to sacrifice somebody in order to buy himself out of the need to punish us.”[3]

[1] The situation is not unlike the equality of all peoples before the Abbasid caliph, to which I shall refer in the next chapter. I would argue that the resemblance between Islamic theology and the reality of the Islamic empire in which it developed is probably not mere coincidence.

[2] Alma 42:25.

[3] In these terms, Christian belief does seem a bit strange. Paul was right. The doctrine of “Christ crucified” does appear “unto the Jews a stumbling-block, and unto the Greeks foolishness.” (1 Corinthians 1:23.) We can hardly be surprised that a modern Muslim, heir to a Semitic religion mingled with Greek philosophical thought patterns, would find it difficult to accept.