(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Continuing with the story:

In 1882, young Jews calling themselves “Lovers of Zion” began actively to promote immigration to Palestine among their people. This was the beginning of what came to be known as “practical Zionism,” which advocated building Jewish settlements in Palestine. (It was “practical” in the sense that it pushed for real action to implement the dream Jews had been dreaming for nearly two millennia.) Jews returning to Palestine in the late 18OOs and early 19OOs began the heavy work of draining swamps, digging wells, replanting forests, and reclaiming arid land for cultivation through the establishment of irrigation systems. Farm settlements, following various patterns of cooperative organization, began to appear throughout Palestine. These were an important part of Zionist colonization, since many of the Zionists were influenced by the socialist ideals and theories that were widespread among “progressive” European thinkers at the time.

“Political Zionism,” which went beyond merely calling for Jewish settlement in Palestine and sought the establishment of a Jewish state, was largely the creation of an Austrian journalist by the name of Theodor Herzl. He had been a reporter at the notorious 1894 trial of Alfred Dreyfus, in which Dreyfus, a French army officer of Jewish background, was falsely convicted of treason. Dreyfus’s Jewishness had been a central factor in the case. (The great novelist Emile Zola wrote an open letter, J’accuse—”I accuse”—in 1898 that helped to win Captain Dreyfus a new trial and, eventually, acquittal.) Herzl, a nonreligious Jew himself, was shocked to the core. If anti-Semitism, prejudice against the Jews, could become so powerful in a modern, enlightened country like France, it seemed to him that things could only be worse elsewhere. The hope of many Jews to fit in, to assimilate and be accepted as Frenchmen and Germans and Englishmen just like anyone else, now appeared to Herzl to be an illusion. If, after nearly two thousand years of Christianity, it had not yet happened, there was good reason to believe that it never would.

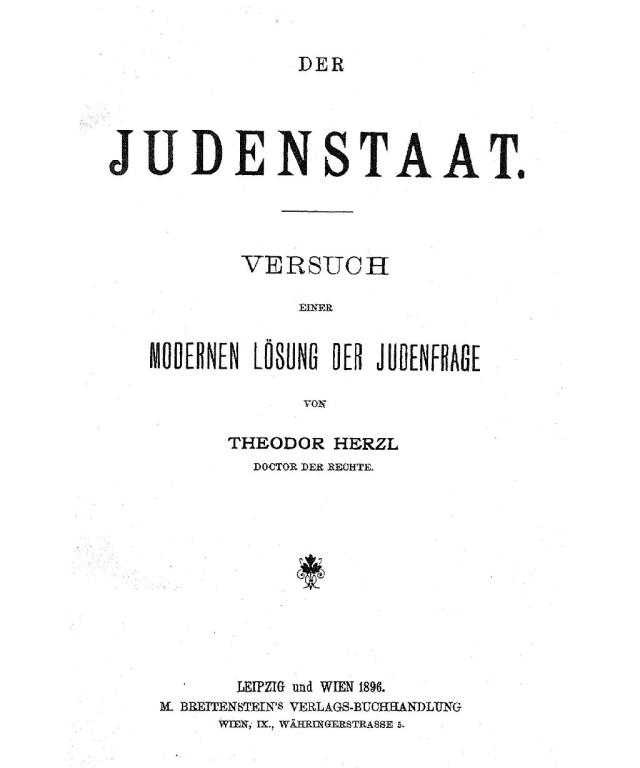

The only possible solution, in Herzl’s view, was for Jews to create an independent Jewish state, in which they would not need to depend on the passing goodwill of Christians. He decided to devote the rest of his life to that cause. It was Herzl, essentially, who put the international Zionist movement in motion. He worked tirelessly, appealing to Jewish leaders and the rulers of many nations, writing, speaking, and traveling indefatigably. In 1896, he published Der Judenstaat (“The Jewish State”) as a kind of charter for political Zionism, bearing the subtitle Versuch einer modernen Lösung der Judenfrage (“Proposal for a Modern Solution to the Jewish Question”). Another important milestone occurred when the First Zionist Congress was held in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897. The movement that would culminate in the establishment of the state of Israel was now well underway.

Not all Jews were enthusiastic about Herzl’s ideas; some, in fact, are still not. Certain Jews, perhaps still hoping to be accepted and assimilated into the countries of their birth, denied that Judaism was an ethnic or national category. Such a claim, they said, just made the situation worse. If Jews themselves were claiming that they were not really Germans, or not true Frenchmen, but had primary loyalty to another, foreign nation, how could they possibly complain when German and French anti-Semites accused them of precisely that? Others rejected political Zionism on the belief that only God could or should restore the Jews to their ancient homeland.