Some notes that I wrote up, at the request of a committee in Salt Lake City, back in January 2017:

Preliminary Remarks

Perhaps the crucial thing to keep in mind about translations of the Qur’an is that they play a sharply subordinate role in Islam, especially when compared to the importance of biblical translations in Christianity.

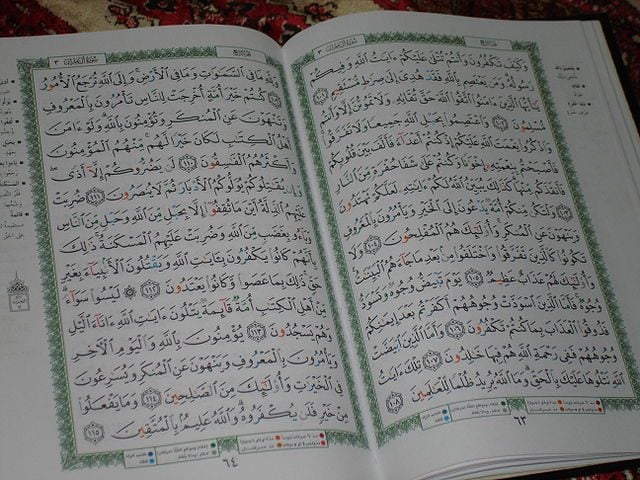

They are, for example, not authoritative. That is, while (especially) non-academic discussions in Christian circles (and, specifically, in LDS circles) are commonly based on translations of the Bible (and, for non-English speaking LDS, the other Standard Works), references to the Qur’an in Muslim discussions always refer to the Arabic original text, even if those engaged in the discussion aren’t really Arabic speakers and even if they then move to a translation. When the Qur’an is cited in prayer services at mosques and other Muslim gatherings, it is always cited in Arabic first—and then, if necessary, in another language. And no serious issue of doctrine or practice would ever be resolved on the basis of a translation.

Strictly speaking, in Muslim belief, the Qur’an is only really the Qur’an in its original Arabic.

It is considered to be the literal word of God, the words actually spoken by God—but, again, only in the Arabic original revealed to Muhammad.

For Muslims, translations exist as a tool for studying and understanding the original Arabic text.

(Fewer than 20% of the world’s Muslims speak Arabic, so the vast majority of those who seek to read it are reliant to a greater or lesser degree upon translations. But they recognize this as undesirable. (By contrast, presumably very few Christians regard an inability to read the New Testament in its original Greek as even remotely a serious defect.)

This analogy might help to explain the attitude: In a sense, the proper parallel to the Qur’an in Christianity isn’t the Bible but Christ himself. Just as Christ is believed by Christians to have been the “incarnation” (literally, the “enfleshment”) of God and the literal physical presence of God (the divine “Word”) in our world, the Arabic Qur’an is believed by Muslims to represent the literal physical presence of the Divine among us. (They believe Jesus to have been a prophet, but not the Son of God, not divine.) We might coin a word—“inlibration,” or, literally, “embookment”—to capture this notion of the nature of the Qur’an.

Thus, devout Muslims believe that there is spiritual value in learning to recite the Qur’an in Arabic even if they can’t read or understand Arabic. For this reason, editions of the Arabic Qur’an have sometimes been published in the Roman alphabet, so that non-Arabs can sound out the words and recite them with reasonably good pronunciation.

There’s a “sacramental” quality to this: A Muslim reciting the Arabic Qur’an is becoming one with the divine Word in somewhat the same way that Catholics believe that they are “becoming one” with deity by consuming the consecrated wafer—which Catholics believe to be, in a mysterious way, the actual flesh of Christ, not merely a memorial—at communion or mass.