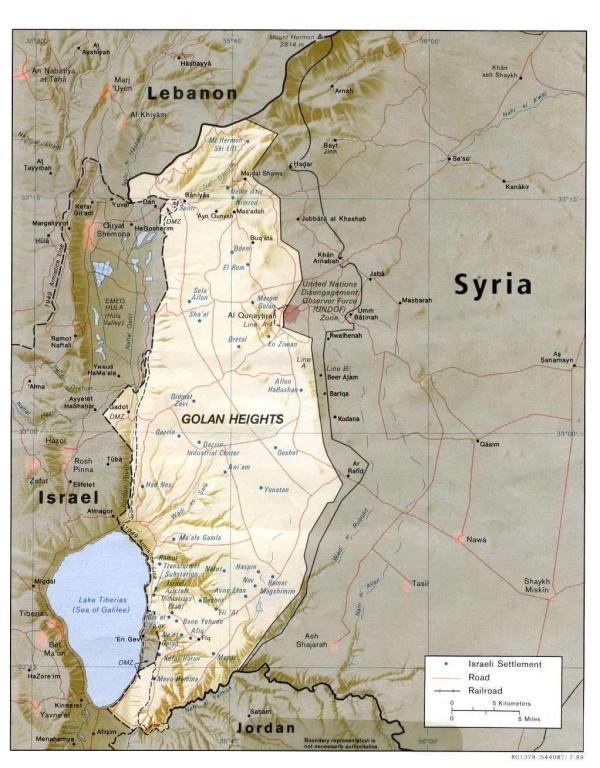

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

The book manuscript continueth:

The trouble was, nobody had asked the Druze and the Sunnis and the Shiites whether they wanted to be part of this new and rather artificial Christian-dominated state. And, in fact, the overwhelming majority seem to have resented it from the beginning. They would have preferred to have become part of Syria, a fully Arab and fully Muslim state. Nonetheless, the leaders of the various religious factions eventually worked out an arrangement which left most Lebanese temporarily satisfied. According to that agreement, the so-called National Pact of 1943, the Muslims would give up their desire for union with Syria if the Maronites would cut their ties with France and accept the notion of Lebanon as an “Arab” country, if not a Muslim one. The Lebanese president would always be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister would always be a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of the parliament would always be a Shiite. In order to guarantee their predominance, Christians were assured six parliamentary representatives to every five representatives of Muslim background.

This arrangement was probably not entirely unfair at the time it was instituted. But, with the benefit of hindsight, it is hard to deny today that the nation of Lebanon was the product of serious design error. It was probably headed toward civil war from the beginning. For one thing, population figures do not remain static. And while Lebanon’s peculiar formula for religious representation was roughly appropriate for a time when Maronite Christians formed a majority of the Lebanese population, they did not retain their majority status. By the 1970s, Christians formed only about a third of the population, while the Muslims and the Druze together represented nearly two-thirds. But when Muslims sought political reforms to bring the National Pact into line with new realities, the Maronites refused. And to make a point, they began to organize private armies, unaffiliated with the state. This was the time, for example, that saw the beginnings of the notorious Phalangist militia, founded by the Gemayel family, which still plays a leading role in the politics of Lebanon. In response, the Lebanese Muslims and the Druze organized their own private armies. The situation was now thoroughly polarized, and no democratic government can last long without conciliation and compromise. Lebanon’s sad collapse into feudal anarchy was underway.

But the situation was far more complicated than a mere confrontation between the Muslims and the Druze, on the one hand, and the Christians on the other. There were conflicts within conflicts and intrigues within intrigues. The Sunni Muslims had done rather well under the old National Pact. They were the wealthiest, the best educated, the most urbanized of the Lebanese Muslim population. The Shiites, by contrast, were quite poor. Concentrated in the southern countryside, they were relatively unsophisticated and poorly educated. They were the “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” the beasts of burden for the more prosperous portions of the population, and were accordingly looked down upon by both Maronites and Sunnis. For years, they did not publicly protest. But this would not last forever.

Posted from Tiberias, Israel