Perhaps the most serious threat to theistic belief is the problem of evil. If God exists, and if God is both good and all-powerful, evil is difficult to explain. Again assuming that he exists and that evil exists, God is either not good or he is not all-powerful. He either cannot prevent evil or chooses not to do so. (Perhaps, indeed, he even wills it.)

This is a thorny problem, and I won’t pretend to resolve it in a blog post, nor even to resolve it to everyone’s satisfaction in a virtually infinite series of blog posts.

However, I will point out that, in my view, the concept of eternal life and postmortem reward helps to mitigate the problem of evil. But that’s a topic for further discussion, on another occasion.

For now, I point out that the problem of evil is typically divided into two distinct parts: the problem of human evil and the problem of natural evil.

A response to human evil — e.g., murders, theft, rape, abuse, cruelty, dishonesty, and so forth — is possible on the grounds of human freedom. This world is not, a defender of theism might point out, the world that God wills. And it’s arguably not God’s fault. If people followed the Ten Commandments, for example, or lived according to the Sermon on the Mount, a great deal of human evil would be eliminated. So long as God permits human freedom, alas, human evil is possible.

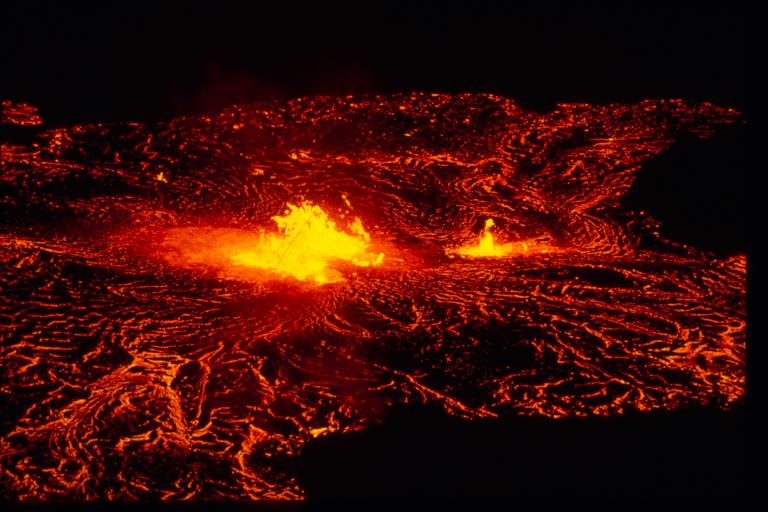

But what about natural evils? A great deal of human suffering comes from pestilence and disease, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and the like.

I offer here a brief note on one class of such natural evils:

The principal areas where earthquakes and volcanic activities occur fall at the intersection of Earth’s tectonic plates, which, in their movements, create and then suddenly release enormous pressures and stress and/or provide seams through which magma can rise to our planet’s surface.

But, as it happens, such tectonic activity may be indispensable to the emergence of life in the first place:

See, for example,

(For a dissenting view, see “Does a planet need plate tectonics to develop life?”)

If tectonic activity really is essential to life, or at least to complex life, this may be relevant to reflections on at least that part of the problem of natural evil.

In the first article, incidentally, you may be surprised at the prominent role played by the film director James Cameron (Terminator, The Abyss, Titanic, Avatar, etc.). He is, as it turns out, a very serious and quite intrepid oceanographic explorer. His name figured prominently at the National Geographic Museum when we visited it yesterday. One reason, obviously, was the special exhibit on the H.M.S. Titanic that was on display. But Cameron is actually a serious explorer. I’m impressed.

Posted from Washington DC