(Image from Wikimedia CC)

I’m sometimes assured that even religious scientists don’t allow religion to infect their science. Instead, they compartmentalize it and keep it strictly separate from their rational thinking. And this, say such critics of religion, is the best case scenario. More commonly, religion is the irrational enemy of science.

James Hannam’s book The Genesis of Science: How the Christian Middle Ages Launched the Scientific Revolution (Washington DC: Henry Regnery, 2011) argues that such assumptions are, at a minimum, simplistic caricatures.

Hannam received a bachelor’s degree in physics from Oxford University and then earned his doctorate in the history of science at the University of Cambridge. Here, he discusses a vitally important person and a pivotal achievement in the rise of modern science where it is flatly (and significantly) not true that religious beliefs were kept strictly separate from scientific efforts:

Born in 1571 near Stuttgart in Germany, Johannes Kepler . . . was a bright child and managed ot win a scholarship to a secondary school and thence to the University of Tübingen. His eventual aim was to become a priest. Religion was the central theme of Kepler’s life — both with respect to his own beliefs and the social climate in which he lived. He was an unusually devout man at a time when strong religious views were commonplace. (291-292)

For Kepler, the most important fact about the world was that God had created it. Like Copernicus, Kepler was convinced that the structure of the heavens had to reflect the perfection of its creator. This perfection, he thought, would reveal itself best through the precision of geometry. (293)

Kepler rejected the defeatism of the skeptics, although his reasons were religious rather than scientific. As far as he was concerned, the heavens must reflect their maker. “For a long time, I wanted to be a theologian,” he wrote, “now however, behold how through my effort God is being celebrated through astronomy.” As the Bible itself states: “The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament shows his handiwork.” There was no imprecision about God and he did not make eight-minute mistakes. Nor was he the capricious sort who would make the heavens into an unsolvable puzzle. If the paths of the planets were ordained by God, then they must be simple and elegant. In keeping with his faith, Kepler was absolutely unwilling to abandon the axiom of uniform motion. But the need for planets to move in circles was a Greek addition to that basic principle and he could drop it without compromising his belief in God’s fidelity.

Copernicus had also derived his astronomical ideas from his theology. However, for all his calculations, he had failed to achieve total empirical accuracy because he was committed to movement in circles. Now Kepler completed the chain between religion and science. His ideas about God provided his hypothesis, he had the mathematical ability to turn his ideas into a system, and, at last, Tycho’s data meant he could check to see if his system was actually true. (295-296)

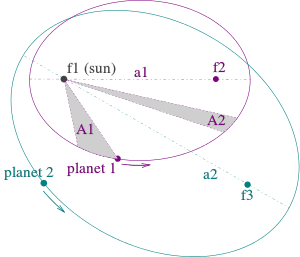

From such a background emerge “Kepler’s Laws” of planetary motion and his revolutionary idea that the orbits of the planets are elliptical rather than circular.

[Kepler] saw his science as a religious duty and wrote as if it were a complicated piece of theology. . . . Sheet after sheet of calculations [in his notebooks] are punctuated with mystical speculation and prayers. Nevertheless, it remains true that Kepler cracked the mystery of the planets’ movements because of his faith in God’s creative power. (296)