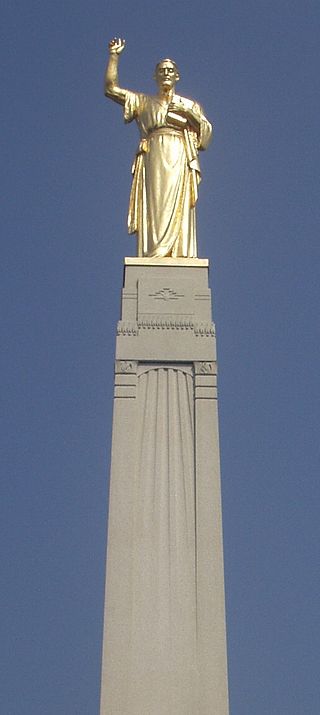

(Wikimedia Commons)

In response to the absolutely deafening clamor of entreaties and demands for me to post the text of my introduction at last night’s presentation by Drs. Royal Skousen and Stanford Carmack — I know that the clamor has been deafening because I haven’t heard it at all — I hereby offer what I said at the event.

By the way, we had an very good audience last night. So far as I could see, the auditorium of the Hinckley Center was full.

I introduced Royal Skousen, who himself introduced Stan Carmack.

Anyway, here are the remarks I gave:

The Interpreter Foundation, which I chair, is delighted to co-sponsor this gathering tonight with BYU Studies. Moreover, it’s a genuine personal honor to introduce to you my colleague and friend Royal Skousen.

Professor Skousen received a Ph.D. in linguistics from the University of Illinois in 1972. Thereafter, he taught at the University of Texas at Austin until joining the faculty at Brigham Young University in 1979. During the years since then, he has been a visiting professor at the University of California at San Diego and a Fulbright lecturer at the University of Tampere in Finland, as well as a fellow of the Max Planck Institute in the Netherlands. He has published significantly and internationally on linguistic theory and quantum computing, including the volumes Analogical Modeling of Language (1989), Analogy and Structure (1992), and Analogical Modeling: An Exemplar-Based Approach to Language (2002). Since 2003, he has served on the editorial board of the Journal of Quantitative Linguistics—the official periodical of the International Quantitative Linguistics Association.

In 1988—thirty years ago—in addition to his other scholarly efforts, Royal Skousen began the Book of Mormon critical text project, which provides the occasion for our celebration tonight.

The central task of the project is and has always been to restore the original English text of the Book of Mormon, to the extent possible, by scholarly means. However, in the course of the three decades of meticulous scholarship that he has dedicated to this effort, Professor Skousen’s work has yielded a number of notable results that exceed even that very worthwhile goal.

Before I proceed further, though, I need to recognize two other people who have contributed enormously to the project:

Having met Sirkku Härkönen during his mission in Finland, Royal married her in 1968. Anybody who knows them and this project at all well understands how involved, supportive, and indispensable she has been to it.

Also essential to the success and the quality of the project has been Jonathan Saltzman, whose superb abilities as a book designer (which I know at firsthand from my involvement with BYU’s former Middle Eastern Texts Initiative) have ensured that the project’s volumes are not only scholarly landmarks but aesthetically elegant and marvelously clear.

We’re here tonight to mark the appearance of two massive books bearing the title The Nature of the Original Language. Together, they form Parts Three and Four of Volume Three of the Book of Mormon critical text project.

Even if you’re as yet unacquainted with that project, those numbers should convey some sense of its scope. Altogether, Volume Three is titled The History of the Text of the Book of Mormon. Parts One and Two of Volume Three bear the title Grammatical Variation.

Volume One, which appeared in 2001, is titled The Original Manuscript. Volume Two, The Printer’s Manuscript, was published in two parts. Volume Four, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon, was published in six parts and has now appeared in a second edition.

These are big books, in every sense of the word big.

Moreover, in 2009, Yale University Press published Royal Skousen’s edition of The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text—a volume that, if I had my way, would be in the home of every Latter-day Saint who reads English.

It’s very possible that no other text (religious or secular) has undergone such complete and thorough analysis as the Book of Mormon has at Professor Skousen’s hand. The critical text project has made full use of the most modern techniques, including sophisticated computerized collation. And I can think of no case of academic textual criticism that is so very much the product of a single scholar’s consecrated labor. Royal Skousen believes—and we should, too—that the Book of Mormon is sufficiently important to deserve such remarkable commitment.

As Grant Hardy of the University of North Carolina observed in a 2006 review of the project’s publications by that point,

Two hundred years from now – long after people have stopped reading anything on the Book of Mormon now in print – students of the Book of Mormon will still be poring over Skousen’s work. What he has accomplished is nothing short of phenomenal.

If I were asked to identify the single most noteworthy aspect of this project, I think it might be what I’ve previously called, and will call again, Royal Skousen’s fierce integrity and independence.

When Adolph Ochs assumed control of the New York Times in 1896, he famously declared the newspaper’s intention to publish the news “impartially, without fear or favor.” Whether the Times has actually lived up to that lofty vow is dubious, but that Royal Skousen has done so is beyond reasonable dispute. While he has willingly accepted input from trusted fellow scholars, he has made all of the final editorial decisions himself. He does not tolerate carelessness or interference from extra-academic agendas. There have been no committee decisions. There has been no dictation from the Church, let alone from any other entity or individual. It’s all about rigorous, demanding scholarship. And he has followed the facts wherever they have led, no matter how surprising or perhaps even uncomfortable the results might be—as will be plainly illustrated tonight.

What have been the results? Thirty years ago, we knew little or nothing about the transmission of the Book of Mormon text; now we know a great deal, almost all of it, if not indeed all of it, as a result of this undertaking. The critical text project has produced the first complete transcriptions of the Book of Mormon manuscripts, both the Original Manuscript and the Printer’s Manuscript—including newly discovered fragments of the Original Manuscript.

We now recognize more fully than ever before the remarkable consistency in the phraseology of the Book of Mormon.

We have gained new information about the Book of Mormon’s translation and publication.

For example, we now know that, for the portion of the Book of Mormon from Helaman 13 through the end of Mormon, the 1830 edition was set from the Original Manuscript, not from the Printer’s Manuscript. Why? Because, in February 1830, Oliver Cowdery and others took the completed Printer’s Manuscript with them to Canada in order “to secure a copyright” to the Book of Mormon in the British realm. Thus, in order to continue his work, the 1830 typesetter used the Original Manuscript to set the text for this part of the Book of Mormon.

We have a clearer idea about who really counts as a witness to the translation of the Book of Mormon and regarding exactly which aspects of their accounts can be accepted as eyewitness testimony.

We have learned more about the corroborating witnesses to the Book of Mormon plates. In 2014, as something of a spin-off of his textual work, Royal Skousen published “Another Account of Mary Whitmer’s Viewing of the Golden Plates” in Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture. From it, we understand the very human circumstances that led to Mary’s experience with the plates: She was planning to order Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery from her home because, rather than helping with the household chores, they were taking breaks from their work on the dictation of the Book of Mormon in order to skip rocks on a nearby pond. Any woman here will understand her frustration. Any believer here will understand how that frustration vanished when she was shown the golden plates.

The project has discovered 606 new textual readings that have never been published in any standard edition of the Book of Mormon. Included among these are 241 textual changes that, if adopted, would show up in translations of the English Book of Mormon into other languages—that is, they would make differences to the meaning. About 15 name changes have been discovered.

The project has revealed Hebrew-like—or, anyway, non-English—expressions in the original text that have subsequently been removed by editors. And it has shown that such grammatical editing, since the original revelation to Joseph Smith, has been human editing subject to human error—even when the editor was Joseph himself.

Tonight, we will hear what astonishing new insights the project has given us into the original language of the Book of Mormon.

As I said in a previous introduction to a lecture by Professor Skousen, I believe that, in introducing him and, more importantly, by being associated with him as a friend and colleague and supporter, I’m privileged to participate in an important chapter in the history of the Book of Mormon and even in the unfolding history of the Restoration.

I’m happy that you’re here. I’m happy to be here myself. And now we’ll hear from Royal Skousen.