(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

Differences (continued):

Related to this point is the fact that, for Muslims, we are not all brothers and sisters because we are the children of the same God. They understand what Christians mean when such words are used, and may even be sympathetic to the point a Christian might be trying to make, but, in their view, God does not have children. We are creatures of God—no more related to Deity than the light bulb was related to Thomas Edison.

Another absolutely crucial difference: In Islam, God is sovereign and free. He can forgive (or not forgive) anyone he wants. Accordingly, Muslims see no need for an atonement. And their prophetic but human Jesus lacks the innate capacity to effect an atoning sacrifice. Mormonism, on the other hand, speaks of a cosmic law of justice that has to be satisfied, which even God (in some sense) is not free to ignore, and of Jesus as the perfect and divine sacrificial offering who settled a debt on our behalf that we could not have taken discharged by ourselves.

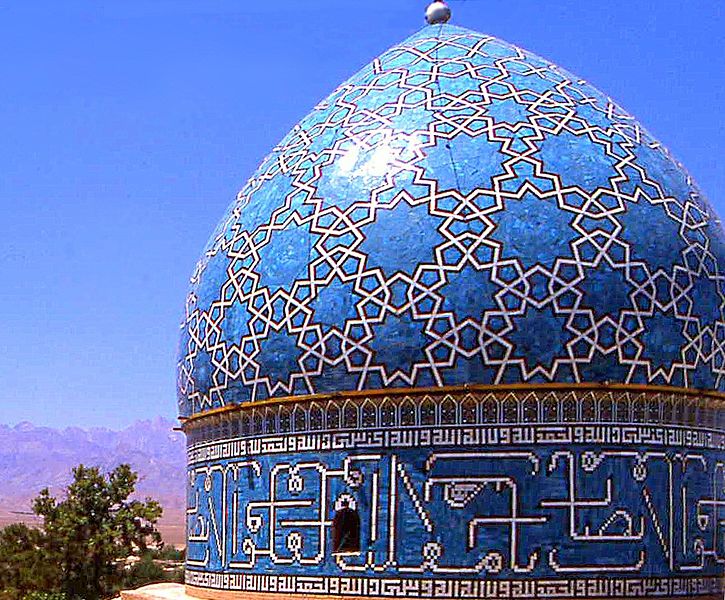

The Qur’an is absolutely central to Islam and Islamic culture, in ways that go far beyond the centrality of the Bible and other scriptures among Latter-day Saints. Qur’anic recitation—the Qur’an is chanted, and there are experts who actually become popular “stars” because of their chanting abilities and the quality of their voices—begins and ends each broadcast day on radio and television. Qur’anic verses are carved into stone on public buildings and sewn into tapestries and wall-hangings and inscribed by expert calligraphers on metal trays and framed parchments. Students learn to read and recite the Qur’an in Arabic, even if Arabic is not their native language. Great emphasis is placed on reciting the Qur’an properly, but relatively little is placed on understanding what it means. The words themselves are thought to be the words of God, and so there is power in simply saying them. But there are no study editions of the Qur’an, and it is unthinkable that anyone would ever take a MagicMarker to a Qur’an to highlight certain passages, or make notes in the margin. Muslims I have known have been appalled to see Latter-day Saints place their scriptures under a chair at a meeting; the Qur’an should never touch the ground, and readers should, ideally, have washed their hands and made themselves ritually pure before opening it. Some Western scholars have even argued that the best analogy to the Qur’an in Christianity is not the Bible, but the (mainstream) Christian view of the Son himself. Both Jesus and the Qur’an, they contend, can be regarded as “the Word,” as God’s eternal utterance, the tangible manifestation of God in this world. I think the comparison is apt. The same arguments that swirled around the relationship of the Father and the Son in the early apostate Christian church and culminated in the Nicene Creed were made, in Islam, about the Qur’an. (Was it created, or eternal? Etc.)