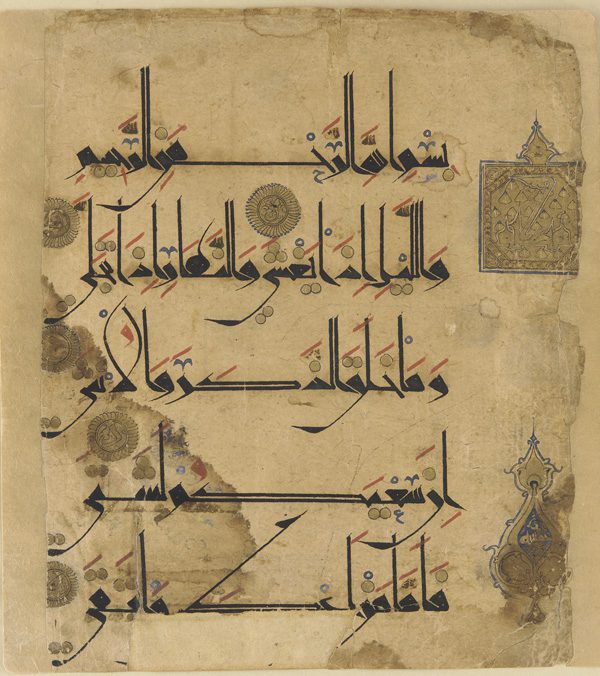

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

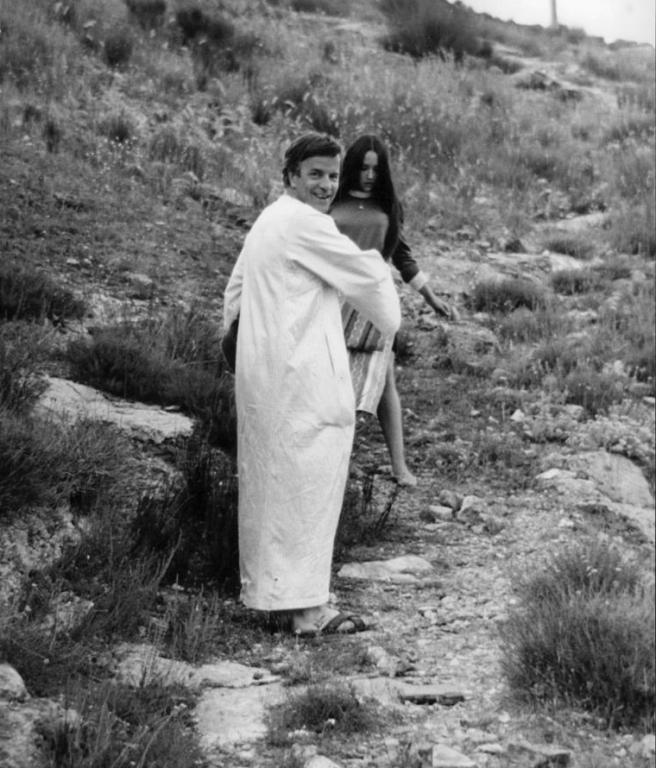

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

Preface: Kufic Arabic script is style of writing the Arabic language. It originated very early — presumably in the city of Kufa, in Iraq — but it’s still sometimes used today. It features the same Arabic letters that are commonly used elsewhere, in other script styles, but, in Kufic, they’re elongated and angular. (See above.) This makes Kufic script especially well-suited for, among other things, architectural inscriptions in stone.

Now to my anecdote:

Long ago, when my wife and I lived in Egypt, we often attended concerts and plays and lectures in Ewart Hall, on the old campus of the American University in Cairo that was located directly adjacent to Tahrir Square.

Above the stage in Ewart Hall was an inscription, in Kufic-style letters, that puzzled me for at least a year’s worth of attendance at events there. Maybe longer. I tried and tried and tried to read it, but I couldn’t recognize so much as a single actual word. This was profoundly discouraging to me, because it indicated that I had even further to go, in learning Arabic, than I had imagined.

And then, one evening, a spectacular realization came to me. I had been trying to read the inscription from right to left, because that’s the way Arabic script runs. Suddenly, though, it dawned on me that the inscription wasn’t even in Arabic at all. It was stylized Roman letters, made to resemble Arabic script. In fact, it was in English — a language that I already knew fairly well — and it ran, as English writing does, from left to right.

Once I recognized it as an English inscription, I could read it very easily. This is what it said:

“Let knowledge grow from more to more, but more of reverence in us dwell.”

It’s from the 1849 poem “In Memoriam A. H. H.,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809-1892).

I’ve thought about this experience many times over the years. It illustrates, for me, the difficulty that we sometimes have in seeing things that we’re not expecting to see.

My efforts were bent so intensely on learning to read Arabic at the time that, as an overreaction, I tried to read an admittedly Arabic-looking text as if it actually were Arabic rather than my own native English.

I had an analogous experience on another occasion: I had been reading so much Arabic, going from right to left, that, one day, while reading an English-language book and having just completed a page, I absentmindedly turned to the next page the way that I would do with an Arabic one. But the “next” page was a page that I had already read, and I thought that my book was defective, repeating pages. It took me surprisingly long — by which I mean several seconds — to see the stupid mistake that I had made.

But back to the first story, about that Tennyson inscription in Ewart Hall: Sometimes, we can’t see what’s clearly before our eyes because we’re so thoroughly certain of what we ought to be seeing.

***

We’re just back from a good Utah Opera performance of Charles Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette. Anya Matanovic was excellent in her title role.

I have a long history with this story. For example, I developed a major high school major crush on Olivia Hussey when I saw her in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 film version of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

And my wife and I have visited the actual house in Verona where Juliet didn’t live and where she never stood out on the balcony conversing with Romeo.

On Saturday, we saw a performance down in Cedar City of The Liar, a play in iambic pentameter by David Ives that was adapted from Pierre Corneille’s 1644 play of the same name (Le Menteur). It was hilarious. Very clever. I would recommend that you see it, but, alas! — or perhaps I should say hélas! — we saw it on the very last day of the Utah Shakespeare Festival’s fall season. It’s now over.

And another interesting dramatic experience from a couple of days ago was seeing the 2018 Dutch film The Resistance Banker (in Dutch, Bankier van het Verzet), about the brothers Walraven van Hall and Gijs van Hall and the spectacular “bank fraud” by means of which they managed to finance a large part of the Dutch Resistance right under the nose of the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. Although it’s a dramatic film, the story is true. Perhaps it’s because I’m unusually interested in the Second World War, but I found it fascinating.