(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

BYU’s Departments of Asian and Near Eastern Languages and of Philosophy had an informal lunch today with the University’s president (Kevin Worthen) and its academic vice president (James Rasband, who contributed the foreword to the Interpreter Foundation’s 2017 festschrift volume in honor of John W. Welch). My faculty appointment is in Asian and Near Eastern Languages, which is why I participated in the lunch, although I’ve also taught courses in Philosophy (and, in fact, will be doing so again this next term). The get-together was interesting, and was devoted almost entirely to a lively and candid series of questions and answers.

But, somehow, during the time that we were sitting there, I began to think of one of my great disappointments at BYU.

During most of the years that I was seriously involved in the Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies, or FARMS, and its successor organization, the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, there was a real feeling of excitement and camaraderie as we brought the tools of biblical studies and ancient Near Eastern studies and other such fields to bear on the Book of Mormon, the Book of Abraham, and related topics. We gathered together a constellation of Latter-day Saint scholars with expertise in early Christian literature, Egyptology, Semitics, Islamic studies and Arabic, biblical law, and the like. I actually began to think of something like an emerging “Provo School” of scriptural scholarship, a distinct family of approaches to the topic — born from unique and distinct questions and interests. I thought that maybe we were in the early formative stages of such a thing.

And then I began to think about how the tools that were being applied to the extrabiblical scriptures of the Restoration might fruitfully be applied to yet another extrabiblical text of world scripture, the Qur’an. I began to dream of a “BYU Qur’an.”

There has long been a tendency to see Islamic studies and biblical studies as areas of study that are hermetically sealed off from one another. The Qur’an was, and continues to be, primarily viewed as the beginning of the Islamic tradition — which is, obviously, an entirely legitimate way of looking at it. On the other hand, although it’s relatively late it’s actually older than at least a few of the texts that are included in Jim Charlesworth’s two-volume anthology of the Old Testamant pseudepigrapha — which led me to wonder why the examination of those texts was considered more or less part of biblical studies, while the Qur’an, a Near Eastern text from late antiquity, is not. People who do biblical studies don’t typically do Qur’anic studies. People who do Qur’anic studies rarely if ever do biblical studies.

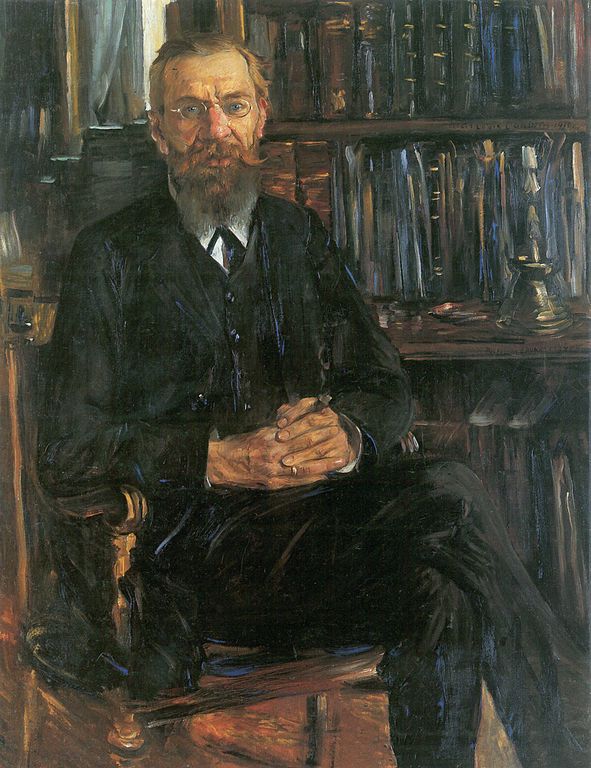

In the old classical days of “orientalism,” however, this wasn’t necessarily so. For instance, the great Julius Wellhausen (1844-1918), one of the originators of the “documentary hypothesis” regarding the Old Testament, also wrote on the New Testament and made extremely important contributions to the study of earliest Islam. And his fellow German Eduard Meyer (1855-1930) published extensively on ancient history generally and on Judaism in particular, and is still fairly well known among Latter-day Saint scholars for his Ursprung und Geschichte der Mormonen (1912), in which he very knowledgeably compared the Restoration to the rise of Islam. They hadn’t compartmentalized their approach to nearly the extent that — for easily understandable reasons — we do today.

My thought was to convene on ongoing seminar in which our people, coming from such diverse disciplines as Syriac studies, Egyptology, Hebrew legal history, patristics, Old Testament studies, comparative Semitics, and the like, would read the Qur’an at a rather leisurely pace together over a period of years and discuss it, noting things that, because of their particular backgrounds and specialties, jumped out at them — but that would not necessarily strike those coming from the more common background of Islamic studies as such. I thought that an interesting volume, a commentary, might result from such an enterprise.

Anyway, that was one of the dreams that died with the upheaval at the Maxwell Institute of 2012.

For all sad words of tongue and pen,

The saddest are these, ‘It might have been’.

John Greenleaf Whittier (1807-1892)