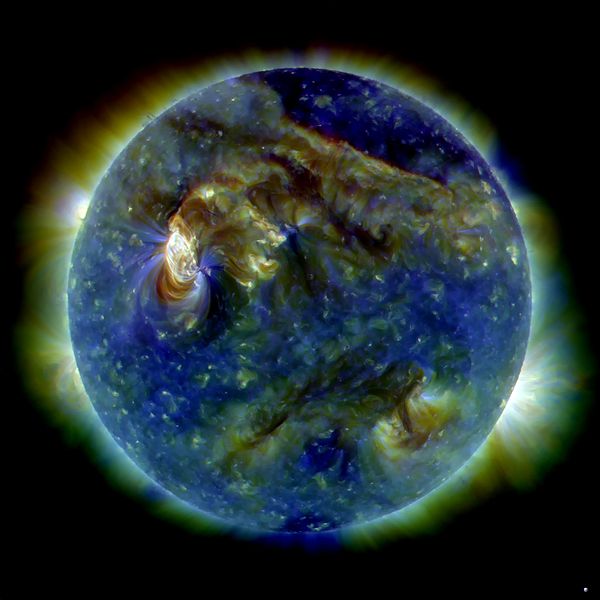

It should be fairly obvious from my blog that I’m interested in science. In fact, my earliest aspiration was to be an astronomer. Really. And I mean really early. When I was five — and for some time thereafter. Moreover, had my poor eyesight not blunted my enjoyment of the night sky, I might really have followed through on that aspiration. However, while I find science fascinating, I’m considerably less enamored of the absurd ideology known as scientism.

Here’s a nice quotation from the late Hugh Nibley (1910-2005), who had a pivotal influence on me (though not necessarily in this regard) later in my youth:

Having renounced all traffic with Religion, the Scientist proceeds to devote hundreds of hours to giving public lectures on “Science and Religion.” This is an interesting paradox:

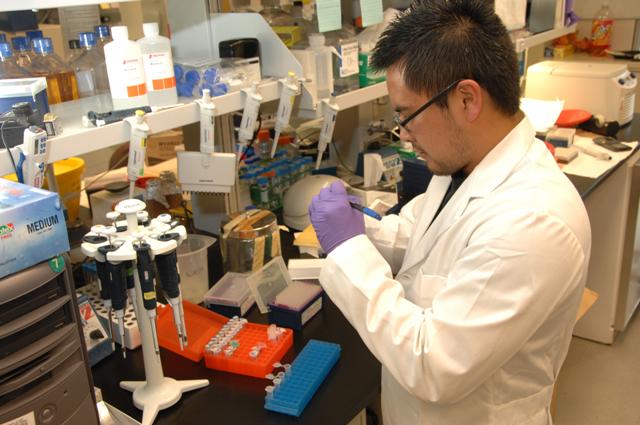

a) The secret of the Scientist’s superiority and success is that he pays strict attention to the problem at hand; limiting himself to the laboratory situation, he rejects all else as extraneous and irrelevant.

b) This means that the problem at hand is everything that counts.

c) If that is so, nothing else counts—Science is all in all.

d) Therefore Science alone can give the answers to the ultimate problems of life.

e) But the ultimate problems of life are exactly what Science must renounce in order to be Science!

For a scientist to talk of, for example, “The Relationship between Science and Religion” is as meaningless as for him to lecture on “The Place of the Supernatural in the Laboratory,”—and for the same reason. His function as a scientist rules out any consideration of either. The greatest chemist alive knows no more about Man’s Origin and Destiny than anybody else does.

The scientist readily admits that he was wrong yesterday, but dogmatically insists that he is right today. We can believe him when he says he was wrong, but can we believe him when he says he is right today? He said that yesterday, too: Science cannot be self-correcting until it knows the correct answers. But as long as it is progressing, the answers will be changing—Science is not self-correcting but self-rebuking.