(Wikimedia Commons)

I do not know what I may appear to the world; but to myself, I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself now and then in finding a smoother pebble or prettier shell than ordinary, while the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727)

Raw and unprocessed notes from a manuscript, drawn from Allen R. Buskirk’s review of Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, which appeared — back during my reign of terror as editor of the FARMS Review, a time of evil, viciousness, and fear when that journal published nothing but lies and mean-spirited ad hominem attacks — in FARMS Review 17/1 (2005): 273–309 as Allen R. Buskirk, “Science, Pseudoscience, and Religious Belief”:

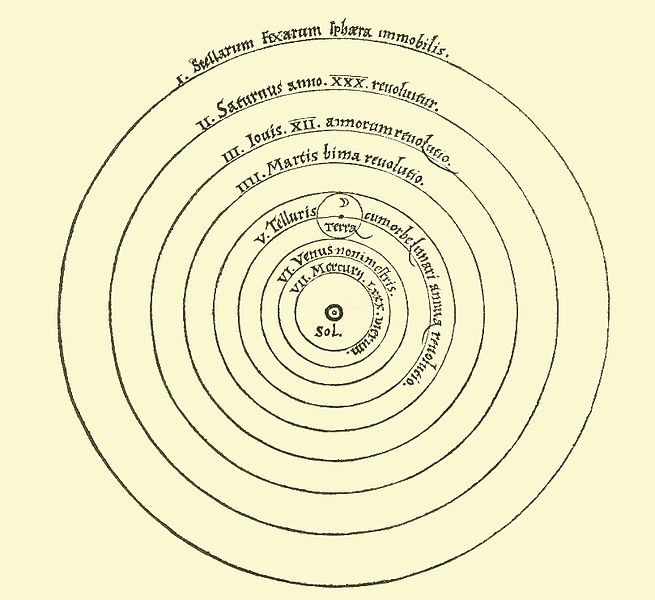

Contemporary science often requires that we ignore the evidence provided by our own eyes in favor of abstract theories. (“Who are you going to believe?” goes the old joke about a quick witted scamp. “Me, or your lying eyes?”) How many have ever seen a quark or a muon or even an electron? What evidence do we really have, speaking of us personally or individually, that the earth orbits the sun? To the human eye, it appears that the sun rises in the morning and sets at night, while the solid earth, terra firma, remains motionless and at rest. What sensory data tell us that the earth revolves annually around the sun? None. Which is why ancient peoples universally — and, on the whole, understandably and reasonably — held to a geocentric view of the universe. But then along came Copernicus (1476-1543), arguing that, in fact, it is the earth that moves around the sun. Which should take precedence? Theory, or common sense and what we can see with our own eyes? Galileo (1564-1642) once expressed his admiration for Copernicus on the grounds that Copernicus let “reason so conquer sense that, in defiance of the latter, the former became the mistress of his mind.”[1] In other words, Galileo admired precisely the fact that Copernicus permitted theoretical principles to override the data presented by his senses. But the surprising truth is that the weight of the actual evidence both in Copernicus’s time and — in part anyway — in Galileo’s time some years later, was against Copernicus’s proposal. That is why the Dane Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), the greatest astronomical observer of his era and, arguably, the greatest in world history to that point, never fully bought into the Copernican model of the sun and its satellites. It was not until approximately sixty years after Copernicus’s death that the data were on hand to begin to vindicate his heliocentric model of the solar system.

[1] Cited in Steven Shapin, The Scientific Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 93. [see original]