Science makes people reach selflessly for truth and objectivity; it teaches people to accept reality, with wonder and admiration, not to mention the deep awe and joy that the natural order of things brings to the true scientist. (Lise Meitner)

I confess that I was unaware of her until very recently — which is symptomatic of the injustice of it all.

Lise Meitner was an Austrian physicist, born in Vienna, whose research concentrated on radioactivity and nuclear physics. In fact, she was a part of the scientific team that first discovered nuclear fission (in uranium, when it absorbs an extra neutron) — and, with her physicist nephew Otto Frisch, may even be the person who coined the phrase nuclear fission in the first place. (They did so in an 11 February 1939 article in Nature.) Her collaborator and team co-leader Otto Hahn eventually won the 1944 Nobel Prize in Physics for that achievement, but she was passed over. Both of them had been nominated several times previously for both the chemistry and the physics prizes, even before their discovery of nuclear fission. (They had, for instance, discovered the element protactinium — atomic number 91 — in 1917-1918.)

In 1922, Meitner published an article announcing her discovery of a process by which, when an inner-shell vacancy in an atom is filled, that same atom emits an electron. In 1923, working independently and apparently unaware of Meitner’s publication, the French scientist Pierre Victor Auger discovered the same phenomenon and, in his honor, it is known as the “Auger effect.”

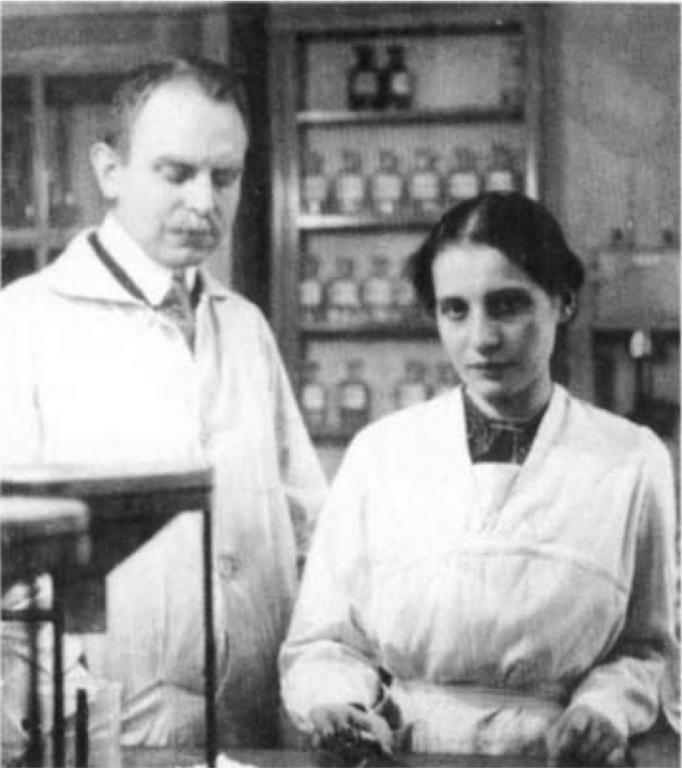

(Wikimedia CC public domain image)

Meitner spent most of her scientific career in Berlin, where she served as a professor of physics and chaired the department at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute. (She had earned her doctorate in Vienna, but had also studied in Berlin — where the great Max Planck, who had never before permitted women to attend his lectures, made an exception in her case.) However, she was ethnically Jewish and so, in the wake of the anti-Semitic Nuremberg Laws issued by the German Reichstag in 1935 under Nazi rule, she eventually lost her academic position. In 1938 — the year of the infamous Anschluss or annexation of her native Austria — she fled to neutral Sweden, ultimately becoming a Swedish citizen.

In Sweden, she found laboratory space at an institute in Stockholm led by the Swedish physicist Karl Manne Georg Siegbahn, a 1924 Nobel laureate. But she hadn’t really been invited, and she was never even given keys to the building, let alone technical support, equipment, or scientific collaborators.

From her perch in Sweden, Meitner was deeply critical of German physicists, including Werner Heisenberg and her own former colleague Otto Hahn, who remained and worked in Nazi Germany throughout the Second World War. She drafted (but apparently did not send) a letter to Hahn that read, in part:

You all worked for Nazi Germany. And you tried to offer only a passive resistance. Certainly, to buy off your conscience you helped here and there a persecuted person, but millions of innocent human beings were allowed to be murdered without any kind of protest being uttered . . . [it is said that] first you betrayed your friends, then your children in that you let them stake their lives on a criminal war – and finally that you betrayed Germany itself, because when the war was already quite hopeless, you did not once arm yourselves against the senseless destruction of Germany.

However, she and Hahn eventually reconciled and remained lifelong friends thereafter.

Meitnerium, element 109 in the Periodic Table, was named after Lise Meitner in 1997 — the only non-mythological woman to have received such an honor — at least partly by way of atonement for her having been ignored by Nobel Prize committee. (In 1955, though, she had won the Otto Hahn Prize! And, in 1966, she and Hahn shared the Enrico Fermi Award with another of their collaborators, Fritz Strassmann. In 2010, long after her death, the Otto Hahn Building at the Freie Universität Berlin was renamed the Hahn-Meitner Building.)

Some consider her the most significant female scientist of the twentieth century. “Our Marie Curie,” Albert Einstein called her.

In 1908, as an adult of roughly the age of thirty, Meitner converted to Christianity — specifically, to Lutheranism. (Two of her sisters converted to Catholicism that same year.) In her last months, she was so frail that she was not informed of the deaths of Otto Hahn and his wife. She died in her sleep, aged 89, on 27 October 1968 in a rest home in Cambridge, England. (She had retired to Cambridge in 1960.) According to her wish, she was buried at St. James parish church in the Hampshire village of Bramley. Her nephew, the aforementioned famous Anglo-Austrian physicist Otto Frisch, composed the inscription that appears on her tombstone:

Lise Meitner: a physicist who never lost her humanity