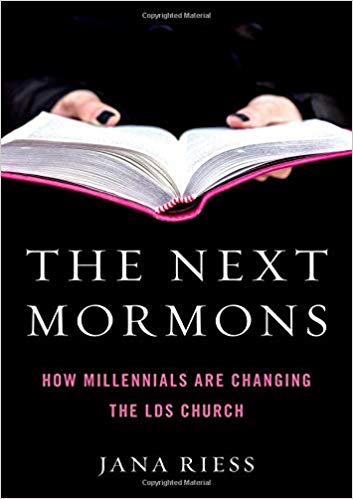

A significant passage from Jana Riess, The Next Mormons: How Millennials Are Changing the LDS Church (Oxford University Press, 2019), 31-32:

Mormons who are divorced or separated are more than twice as likely to be doubters as those who are married (28 vs. 12 percent). . . .

The factor that makes the most difference, though, is not about age or political affiliation or marital status. It has to do with the people around you. . . . In each case, the fewer Mormon family members and friends people have, the more likely they are to be doubters. This is most often the case for those who have zero close friends or extended family members who are Mormon (44 and 35 percent). Doubting also rises as the number of loved ones who have left the church increases. . . . Doubting is least common among those whose closest friends are all Mormon (4 percent) and whose extended family are all Mormon (7 percent).

These findings underscore the importance of social networks in the spectrum of belief and doubt. Relationships matter. When LDS leader Henry B. Eyring used the phrase “infected with doubt” in 2013, he faced heavy criticism. But his metaphor was appropriate at least in one way: doubting is statistically more likely to be associated with the Mormon composition of people’s social networks than it is with their demographic characteristics. Those who have friends and family who are Mormon and stay Mormon tend to be believers, while those with friends and family who are not Mormon or stop identifying as Mormon are more likely to be doubters.

I think this a very important observation, and I offer a slight extension of it:

One of the unique features of attrition from the Church in recent years has been the online emergence of virtual communities — or, I myself might prefer, ersatz communities — of unbelievers that provide something of a reinforcing “social network” for apostasy and apostates. In the old days, if somebody exited the Church he would simply be an isolated “village atheist,” as it were. Now, though, he can join a network of similarly-inclined folks who will welcome him enthusiastically and, in many cases, strengthen his resolve to leave and supply him with additional reasons (or seeming reasons) to justify his departure. In some ways, such “communities” serve as something of a mirror image of the fellowship of the Saints.

Withdrawn into such insular groups, people who were once merely inactive or unhappy at church or weak in the faith or actually unbelieving — and who may even, in some cases, have been seeking fortification and rationalization for their taking leave of the Saints (and, perhaps, to a degree from family and friends) — will often tend to become more radically disaffected, even hostile, urging each other on to ever greater disdain for their former faith community, for doctrines that they themselves once understood and believed, and, not infrequently, for those, including family members, who continue to be faithful believers in its claims (e.g., “Morgbots” or “Mor(m)ons”). To those who continue communicant and believing, however, stumbling into one of these online groups and encountering its sometimes stunning hostility and its seeming inversion of how things look to a believer can be quite a shock.

A striking though plainly quite extreme parallel to this phenomenon, in my judgment, is the online “Incel” subculture.