On Saturday night (27 April 2019), although we’re facing numerous deadlines and really didn’t have the time to do it, my wife and I, after having shared a good dinner from Market Street Grill with her father, attended a Utah Symphony concert at Abravanel Hall in Salt Lake City.

They played three pieces:

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Symphony No. 31 in D Major, K. 300a [297] (“Paris”)

- Joaquin Rodrigo, Concierto de Aranjuez for Guitar and Orchestra

- Robert Schumann, Symphony No. 2 in C Major, Op. 61

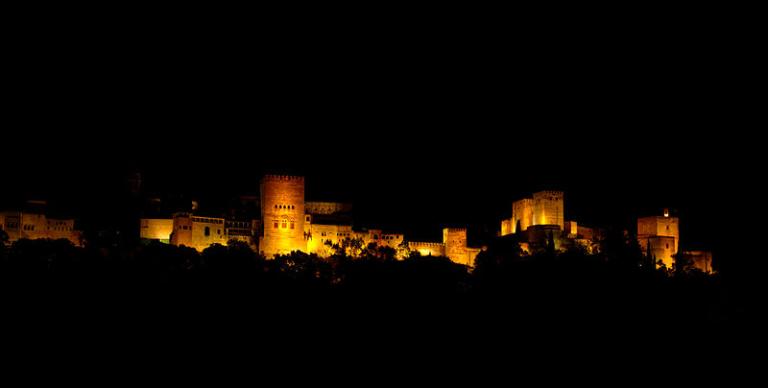

(Wikimedia Commons public domain)

We really went in order to hear Joaquin Rodrigo’s Concierto de Aranjuez, which is one of the truly great pieces for classical guitar — one of my passions. (The Spanish love for guitar, and the Spanish style of guitar playing, obviously derive in part from the eight centuries of Arab presence in Iberia, from AD 711 to AD 1492, and specifically from the influence of al-‘ud, which essentially became the European lute. Flamenco music is plainly Arab-influenced.)

The Concierto de Aranjuez was played on Saturday evening, and played masterfully, by Pablo Sáinz Villegas, who quite deservedly received three standing ovations (following the Rodrigo concierto and then two solo encores, first of a piece from his birthplace of La Rioja in Spain, the name of which I didn’t catch but which is the featured element of this short promotional film that he recorded on behalf of his home, and then of Francisco Tárrega’s Recuerdos de la Alhambra [“Memories of the Alhambra”]). We thoroughly enjoyed his performance.

We also enjoyed the Mozart and Schuman symphonies — and I enjoyed the program notes by Michael Clive that accompanied them.

For Mozart’s “Paris” Symphony, Clive remarks on the composer’s travel correspondence that “His frequent grouchiness went undisguised in his letters. We can only wonder how his correspondence might have been different if he had known that every word would be scrutinized and analyzed by later generations . . . perhaps not at all, since he was never one to self-censor.”

But it ought to give the rest of us pause. If nobody else is scrutinizing us and analysing us, God and his angels are.

Of his “Paris” Symphony and its projected Parisian audience, Mozart wrote to his father, Leopold, “I hope that even these idiots will find something in it to like.”

But there is a weightier “what if” to contemplate here. It’s mentioned prominently in Michael Clive’s program notes, and it echoes a theme that I’ve sounded elsewhere, coincidentally also in the context of classical music:

https://www.deseretnews.com/article/765590762/Beethoven-is-a-study-in-hope-healing.html

Joaquin Rodrigo, the composer of the Concierto de Aranjuez, lived to be 98. That’s obviously unusual. “So many of classical music’s great geniuses,” Clive writes, “led tragically short lives — Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, and Bizet all died in their 30s.”

But tragic sorrows and limitations come in other forms, as well. Rodrigo, for instance, was blinded by diphtheria at age 3. “He credited the apparent calamity of his illness for his lifelong involvement in music.” And, to choose just one instance from his work, many have guessed that the famous second movement of his Concierto de Aranjuez, which was composed in Paris in 1939, was inspired by the horrific 1937 Nazi bombing of the Basque town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War. According to what I’ve read elsewhere, though, Rodrigo’s wife says that part of the “inspiration” for the piece was the utter devastation that the composer felt when they lost their first baby by miscarriage.

Genius is scarcely exempt from trial and sadness.

“Throughout his adult life,” Robert Schumann, the composer of the third piece on the program, “experienced bouts of crippling depression. . . . His illness was so severe that he periodically needed hospitalization.” His life was “a dark struggle.” And he, too, died relatively young, at 46.

He set out to be a virtuoso pianist, but an injury to his hand shut that door before him forever.

“Yet,” comments Clive, “he managed to breathe the most positive elements of Romanticism into his music . . . he was a devoted husband, a productive composer, and a champion of up-and-coming composers.” “In his music we sense light.”

From piano performance, Schumann turned to piano composition, then to full orchestral music, and eventually to symphonic composition.

Even so, Schumann’s work on his Symphony No. 2 “was interrupted by bouts of depression, dementia, and tinnitus — a ringing in the ears that plunged his musical imagination into shadow, like an eclipse. His joints ached, his head throbbed, but he persevered.”

“Music history,” Clive concludes, “is full of what-if questions. One of the most tantalizing is suggested by Schumann’s illness, which afflicted him in both body and mind. It would be treatable today. What if it had been treatable during his lifetime?”

What if?