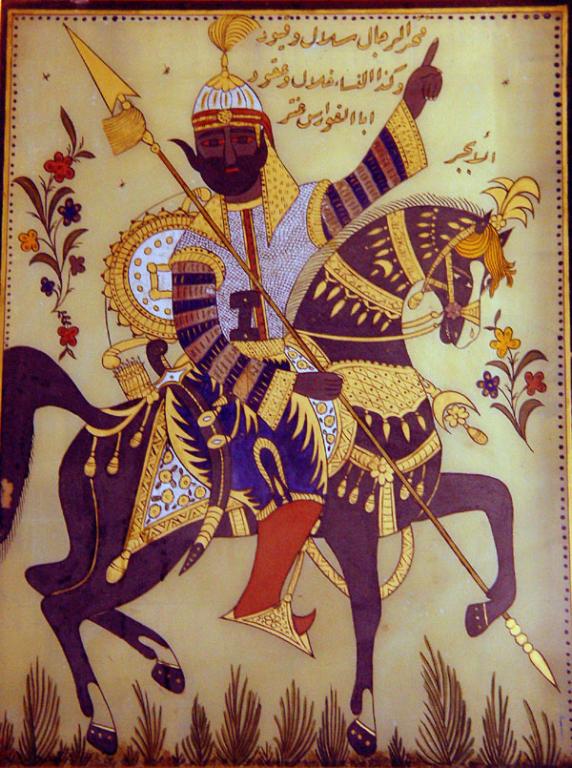

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

There is a story out of pre-Islamic Arabia that I’ve told before. I like it, though, and I’m going to tell it again. As incredible as it may seem, some of you may have forgotten it or even missed it in the first place.

One of the great poets of the Arabic tradition is Antara b. Shaddad, or Antar (AD 525-608). He was the son, it is said, of a Bedouin chieftain and an Ethiopian slave. True, she had been a princess, but now she was a slave, and her son was half black. He didn’t have the status of a freeborn Arab in that society.

There came a time when his father’s tribe was engaged in a fierce battle with a rival tribe, and the rivals were gaining the upper hand. Antara was standing on a ridge overlooking the fight and, as he had been charged to do, was minding the camels of the warriors.

Finally, one of his half brothers climbed up the ridge from the battle and begged him to join the fight. (In some versions, it’s his father.) It has to be understood that the half brothers had long been among those who had mocked Antara for his half-slave origin, and Antara’s father had done nothing to stop them. But, of course, now that the situation was desperate they needed his help. “Sorry,” Antara responded. “I’m a slave and a slave’s son. I’m not worthy to fight alongside you. Slaves know nothing about attacking or defending, and are fit only to milk goats and serve their masters.” “Alright! Alright!” came the reply. “You’re free now! Please help us!”

Antara waded into the fight and, as you might expect, routed the enemy almost single-handedly. And this was merely the first of his heroic adventures. Eventually, his exploits in battle won him the epithet of “the Bedouin Achilles.”

But the story I’m really after is this one:

Some years later, another Arabian aristocrat, encountering Antara, mocked him as a person who lacked a distinguished lineage. By this time, though, Antarah had achieved renown both as a chivalrous warrior and as a poet. And his response to the man who was mocking him is classic:

“You,” he told him, “represent the end of your noble line. I represent the beginning of mine.”

When the Sadducees and Pharisees came to John the Baptist, secure in the nobility of their descent, he told them “Think not to say within yourselves, We have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham” (Matthew 3:9).

Posted from San Diego, California