I delivered the annual Religious Liberty Lecture at the University of Notre Dame Australia, in Sydney, during November of last year. A videotape of that lecture — which focused on Islam and violence and on what my Australian hosts called “Islamophobia” — is now available online:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oFwK33BHHt0

And here is a more or less related item from the British Psychological Society:

“Does Religion Really Cause Violence?”

Which reminds me of a column that Bill Hamblin and I published in the Deseret News back on 12 July 2014:

Critics of religion commonly point to the violence done in its name and, accordingly, pronounce it toxic. And, for obvious reasons, the parade example of its dangers has been Islam.

However, in his 2010 book “A World Without Islam,” Graham Fuller argues brilliantly, via sweeping analyses of world history, that “religion is the vehicle of political confrontation and turmoil, not the cause.”

Fuller, a political analyst specializing in Islamic extremism who formerly served as CIA station chief in Kabul, Afghanistan, and as vice chairman of the National Intelligence Council, isn’t particularly interested in defending theism against its critics. His own religious beliefs, if he has any, are invisible. He simply wants to accurately understand the causes of the tension between the West and the Islamic world so that appropriate steps can be taken to reduce it.

“If there had never been an Islam,” he writes, “if a Prophet Muhammad had never emerged from the deserts of Arabia, if there had been no saga of the spread of Islam across vast parts of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, wouldn’t the relationship between the West and the Middle East today be entirely different? No, I argue, it might actually be quite similar to what we see today.

“Most of the history of the West’s relations with the Middle East is really about the geopolitics of empires and states and not much about religion itself — regardless of the slogans, banners and ideological fervor invoked at the popular level to support the state. Take Islam out of the equation, and there’s a very good chance you’d still find the Middle East at loggerheads with the West.”

Fuller compares the situation to a furious argument between spouses over whether the pasta is overcooked: Their anger may be entirely real, but, plainly, there’s much more going on than mere disagreement over rigatoni. So, too, in the Middle East: Communities, states, politics, power and regional nationalisms are at issue. “Religion serves as a handy tag, constitutes an important element of identity in which the specific theology is really only incidental,” he writes.

As in Africa, Asia and Latin America, so in the Islamic world: “The problems stemming from colonialism and imperialism would exist in equal measure without Islam.”

“Islam,” Fuller admits, “seems to offer an instant and uncomplicated analytical touchstone for most affairs in the Middle East, by which to make sense of today’s convulsive world. By referring to Islam, we can reduce things to a polarized struggle between ‘Western values’ and the ‘Muslim world.’ ” But that oversimplification — what the Swiss Muslim intellectual Tariq Ramadan has described as “Islamizing the problem” — is false and misleading.

Fuller is acutely aware of the prominent place that Islam occupies in current disputes worldwide, but he contends that the faith “has primarily served as flag or banner for other, deeper kinds of rivalries and confrontations taking place.

“The factor of Islam provides focus, color and vigor but is not especially central.”

Tracing rivalries between East and West back to the conquests of Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C., he maintains that Islam is merely the most recent vehicle for expressing resistance to the West, the latest banner under which the old but ongoing geopolitical struggles of the Middle East are perpetuated. Surveying ostensibly religious disputes going back centuries before the rise of Islam — such historical depth is extraordinarily rare in political analysis, but remarkably enlightening (especially with regard to the deep-rooted ancient cultures of the Middle East) — Fuller argues that “religious doctrine is almost never the issue at stake.”

We shouldn’t be surprised, of course, to see the powerful symbols and inducements offered by religion used to mark ethnic “fault lines” and to “sanctify” conflicts. But we shouldn’t be misled by superficial appearances. If Islam hadn’t come along, Fuller plausibly argues, Eastern Orthodox Christianity would have played much the same role. “The Middle East was … quite capable, without Islam, of developing aversion to the West.”

“In the end, I hope to persuade the reader that the present crisis of East-West relations, or between the West and ‘Islam,’ has really very little to do with religion and everything to do with political and cultural frictions, interests, rivalries and clashes.”

Readers of “A World without Islam” may reject some or many of Fuller’s specific recommendations for American foreign policy. But they’ll see the Middle East — and China, India, Europe and Vladimir Putin’s Russia — in fresh and instructive ways.

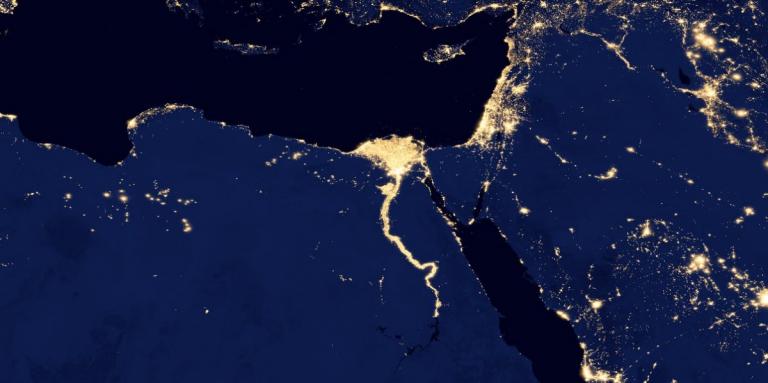

Posted from Cairo, Egypt