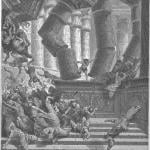

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

I’ve been reading a relatively short book by the distinguished British conservative philosopher Sir Roger Scruton, whom I greatly admire, entitled On Human Nature (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2017). The book is the somewhat revised result of his having delivered three Charles E. Test memorial lectures at Princeton University under the auspices of the James Madison Program there in the fall of 2013. (The director of the Madison Program is the distinguished American conservative philosopher and legal theorist Robert P. George, whom I also greatly admire and who, although a Catholic, has become a great friend to Brigham Young University and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.)

I think that I’ll post a few gems from Sir Roger’s book, and that I’ll start with the insightful passage immediately below. Its focus is, strictly speaking, on interpersonal relationships among earthly mortals such as ourselves, but I think it also very relevant to questions of salvation by grace, “works righteousness,” and divine forgiveness:

Forgiveness cannot be offered arbitrarily and to all comers — so offered it becomes a kind of indifference, a refusal to recognize the distinction between right and wrong. Forgiveness is only sincerely offered by a person who is aware of having been wronged, to another who is aware of having committed a wrong. If the person who has injured you makes no effort to obtain forgiveness and merely laughs at your first moves toward offering it, the impulse to forgive is frozen. If, however, the person apologizes, and if the contrition is proportionate to the offense, a process begins that might have forgiveness as its outcome. The idea of proportionality is important. The person who runs over your child and who then says “Frightfully sorry,” before driving off has not earned your forgiveness. People who take on the full burden of contrition in a case like this must not only try to make amends but also show, through their distress, a full consciousness of the extent to which they have wronged the other, so that their restoration as members of the community must depend on the other’s goodwill. (p. 85)