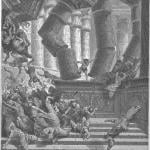

(Wikimedia Commons public domain illustration)

Are the Arabian Nights great literature?

Opinions vary sharply about this question. In the Middle East itself, the literary elites have tended to think that they aren’t, that they’re merely folktales, and have typically ignored them — although that attitude seem to have shifted in recent decades. It’s analogous, perhaps, to the neglect shown by traditional Arab grammarians, lexicographers, and philologists toward the spoken Arabic dialects, collectively called ‘ammiyya, that are actually spoken on the street (by everybody, at all socio-economic levels). These vernacular dialects vary widely from Morocco to Egypt, and from the Levant to Iraq. But traditional scholars have long focused exclusively, or almost so, on the classical language of elite educated writing that is known as fuṣḥá. A friend of mine, reporting on his research into terms of personal address in Egyptian colloquial at a prestigious gathering in Cairo many years ago, actually received an angry response from some in his audience. They demanded to know why he was studying the language of the streets and the gutters rather than that of the Qur’an and great literature — and, ironically, their objections were themselves voiced in Egyptian colloquial. But this attitude, too, seems to be changing.

As to the literary merits of the Nights, though, these are definitely mixed, as is the collection itself. The original Arabic manuscripts, for example, are studded — or, some might say, littered — by hundreds of poems that most translators have dismissed as largely mediocre. In fact, most translators have tended to omit them because they often interrupt the flow of the narrative.

Another way of judging the literary quality of the Nights, however, might be to consider their influence and their readership, which have been enormous and diverse. What child hasn’t grown up hearing — or watching movies and videos — about Sindbad, Ali Baba, and Aladdin? About genies and magic lamps? Who doesn’t recognize the command “Open, sesame!”

Hollywood has certainly paid attention, too, since well before the 1940 Thief of Baghdad and continuing through Disney’s 1992 animated Aladdin, its two direct-to-video sequels, the animated television series Aladdin that derived from it, and its 2019 live-action remake of the same name.

But the Nights have permeated high Western culture, as well. In classical music, for instance, among many other instances that might be mentioned, Carl Maria von Weber (Abu Hassan, 1811), Luigi Cherubini (Ali Baba, 1833), Robert Schumann (Scheherazade, 1848), Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (Scheherazade, 1888), and Carl Nielsen (Aladdin Suite, 1918-1919) have devoted significant works to stories from the Arabian Nights. In western literature, such varied authors as W. B. Yeats, Goethe, Jorge Luis Borges, Flaubert, Stendhal, Dumas, Hofmannsthal, and Tolstoy, H. P. Lovecraft, and Proust have been influenced by them.

Posted from Canmore, Alberta, Canada