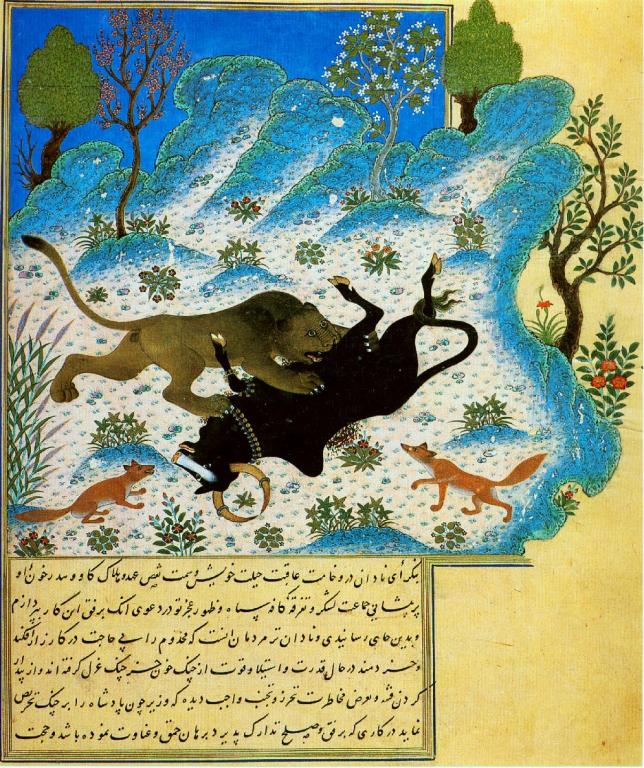

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

One of the books that we read in my “Islamic Humanities” course — in fact, the very first book that we read — is a retelling of the Kalila wa-Dimna or Kalila and Dimna. I would rather have had the students read the text itself (in translation, of course), but I haven’t found a good translation that’s readily and inexpensively available. (That is a serious lacuna — unfortunately, one of many — in the field.)

Kalila and Dimna is a cycle of animal fables that clearly originated in India but that, translated into Arabic from a Pahlavi version by Ibn al-Muqaffa‘ (who died in either AD 756 or AD 759), became one of the very first examples of Arabic literary prose.

Kalila and Dimna are the names of two jackals — in some translations (e.g., I think, in certain medieval Hebrew versions), they’re foxes — who are brothers. They are members of the court of the Lion, who is the king of the animals. You probably won’t be surprised to learn, given the fact that they’re jackals, that their character is suspect. (It seems that jackals seldom have a good reputation, in any culture.)

The Kalila and Dimna was one of the most popular medieval books among Middle Eastern illustrators, and illuminated manuscripts of the fables are common. Once when I was visiting the library of a major foundation in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for some sensitive negotiations, I knew that I had succeeded with the very suspicious head of the library when he suddenly went to his file cabinet — his metal file cabinet! — and pulled out one of the oldest manuscripts of the book known to exist. It wasn’t an autograph manuscript but, he explained to me, perhaps a first- or second-generation copy. Very old, in other words. He handed it to me and invited me to leaf through its pages. I was simultaneously thrilled at the privilege and very concerned. I wasn’t wearing gloves, and I was terrified lest I somehow drop it or tear one of its pages. But I was struck by its elegant illustrations, presumably done for someone of considerable status and wealth.

In my view, the Kalila wa-Dimna should be reckoned among the class of what are called “Mirrors for Princes” books. It is a satire of life in a royal court, which it portrays as a very dangerous place, full of intrigue and betrayal, but it can also be read as a didactic manual of precisely how to survive and prosper in such an environment.