I published the column below in the 22 March 2018 issue of the Deseret News:

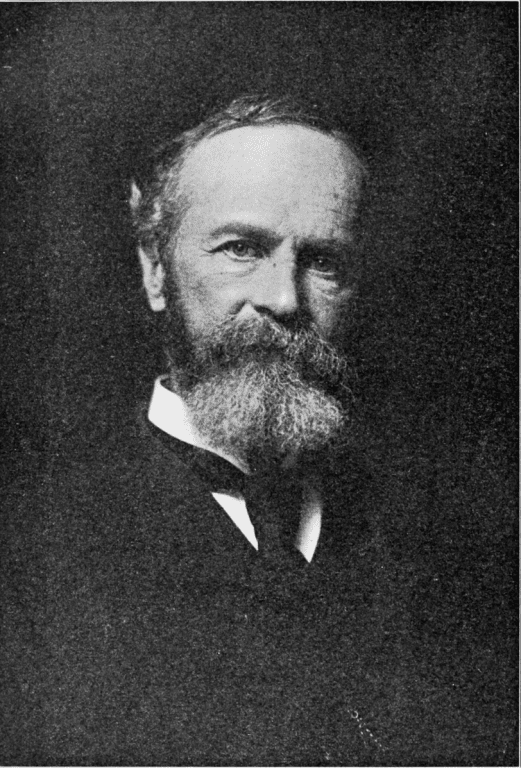

The great Harvard philosopher and psychologist William James (1842-1910) took a very positive view of the effects of religious belief. “We and God have business with each other,” he wrote, “and in opening ourselves to his influence our deepest destiny is fulfilled. The universe … takes a turn genuinely for the worse or the better in proportion as each one of us fulfills or evades God’s commands.”

On the whole, though, the most prominent early figures in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis were not only personally irreligious but vocally anti-religious. Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), for example, described religion as “the universal compulsive neurosis of humanity” and titled one of the books that he devoted to the subject “The Future of an Illusion.”

“Religiosity,” Albert Ellis (1913-2007) declared, “is in many ways equivalent to irrational thinking and emotional disturbance.” “The elegant therapeutic solution to emotional problems,” he claimed, “is to be quite unreligious.” “The less religious they are,” he asserted, “the more emotionally healthy they will be.”

Not everybody agreed. Prominent among those who challenged Ellis’s claim that atheism is psychologically healthier than faith was Allen Bergin, a convert to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints who taught clinical psychology at Columbia University before joining the faculty of Brigham Young University, where he remained until his retirement in 1999.

In a brief new article, Daniel Judd, an associate dean of religious education at BYU who holds a graduate degree in family science and a doctorate in counseling psychology, reports on the basis of 30 years of study that “with few exceptions, my reviews of the academic research have produced little support for the assertions of Freud, Ellis and others that religion facilitates mental illness.” Although occasional contradictions and ambiguities exist, he says in “The Relationship between Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints,”in the winter 2018 BYU Religious Education Review, “the larger body of academic research supports the conclusion that religious belief, and most especially personal religious devotion, facilitates mental health, marital cohesion, and family stability.”

Surveying 540 studies conducted during the period 1900-1995, Judd indicates that “51 percent reported that religion was positively associated with mental health, 16 percent indicated a negative relationship, 28 percent were neutral, and 5 percent yielded mixed results.”

When attention turns to the Latter-day Saints, however, the results are “remarkably positive.” Fully 71 percent of the relevant studies indicate a positive relationship between Mormon faith and mental health, with only 4 percent negative, 24 percent neutral, and one percent mixed. “Latter-day Saints who live their lives consistent with the teachings of their faith experience greater well-being, increased marital and family stability, less delinquency, less depression, less anxiety, less suicide, and less substance abuse than those who do not.”

Significantly, Judd points out, “the majority of the studies with negative outcomes came from the earlier part of the 20th century.” Why? “My inquiries into this anomaly led me to discover that some of the early psychological instruments used to measure mental health were biased against religious belief.” In view of the hostility on the part of major founding figures in the psychological field mentioned above, this is scarcely surprising.

Is everything rosy? Is all well in Zion? Not quite. We should not be complacent. The positive study results notwithstanding, depression, marital problems, anxiety, substance abuse and suicides still occur among Latter-day Saints, and even among those trying hard to be faithful. These require compassionate ministering.

Moreover, as Judd observes, there are certain problems that tend to occur precisely among those trying hardest to keep the commandments and be valiant Latter-day Saints. It’s possible, in such striving, to forget the Atonement and the grace of Christ, and to act — against the plain teaching of scripture — as if we believed that our salvation hinges on us, on our good works. Such misplaced devotion can actually increase depression and anxiety in good people, as, inevitably, we and our families will all fall short of the perfection of God our Father in this mortal life.

This is one of the many areas where regular, deep, thoughtful reading of the Book of Mormon, with its powerful teachings on Christ’s Atonement, can help. For “it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” (2 Nephi 25:23). We don’t need to earn our salvation. We can’t. There are things we must do, but achieving perfection here on Earth is not among them.

Notes: Based upon Daniel K. Judd, “The Relationship between Religion, Mental Health, and the Latter-day Saints,” BYU Religious Education Review (winter 2018): 14-19. For a published testimony from Allen Bergin, see fairmormon.org/testimonies/scholars/allen-e-bergin.

Posted from St. George, Utah