Although this is an archaeological or scientific story, it is also, if you use just a minimal amount of your imagination, a very human one:

In the summaries of the history of the Islamic world and/or the Middle East that I typically give in my classes, one of the pivotal dates that I emphasize to students is AD 1258. Why? That is the year of the catastrophic Mongol sack of Baghdad, which left the city in ruins. (Baghdad never really fully recovered, in a sense.) It is said, in some sources, that the Tigris and the Euphrates ran black for days from the ink of the manuscripts that were cast into the two rivers. Probably a gross exaggeration, but it can serve to represent the magnitude of the disaster that befell the Islamic world through that event. A story like the one above, however, reminds us to think of it not merely in terms of economic setback and loss of cultural heritage but as a human tragedy that ended or damaged the lives of many tens if not hundreds of thousands. And Baghdad was just one of the cities razed by the Mongols during their westward advance from Central Asia.

Happily, that advance was abruptly stopped just a couple of years after the destruction of Baghdad. Here’s a passage from a manuscript of mine:

In 1220, the Mongols poured out of the steppes of central Asia and began the process of substantially destroying the central lands of Islam. The irrigation canals of the Iranian plateau, on which the rulers of Persia had lavished attention and money for centuries, were severely damaged if not utterly destroyed. The area received a blow from which it never fully recovered. These Mongol invaders were great horsemen, highly mobile, who had perfected the art of shooting arrows from horseback at great speeds. Needless to say, this was extremely effective in combat. But I have long thought that the real secret of their success came from their attitude to water. Medieval sources report that the Mongols considered water so sacred that they refused to soil it by bathing in it. Instead, they anointed themselves in horse butter. Now, imagine. After, say, thirty years of horse butter anointings, the typical Mongol of the thirteenth century must have been a fairly potent individual. (All a Mongol army had to do was to get upwind of a town. The place was almost certain to surrender.)

In 1258, the Mongol armies overwhelmed and obliterated Baghdad. Out of respect for the high office of the caliph, however, they did not subject him to the kind of death they had imposed on tens of thousands of others. Instead, they wrapped him up in a Persian carpet and trampled him to death with their horses. Thus perished the greatest Muslim city of the High Caliphal period. It has never really recovered, and the prospects of recovery have seemed dim under Saddam Hussein and the Baathists and, now, amidst the continual violence that followed the toppling of Saddam’s regime.

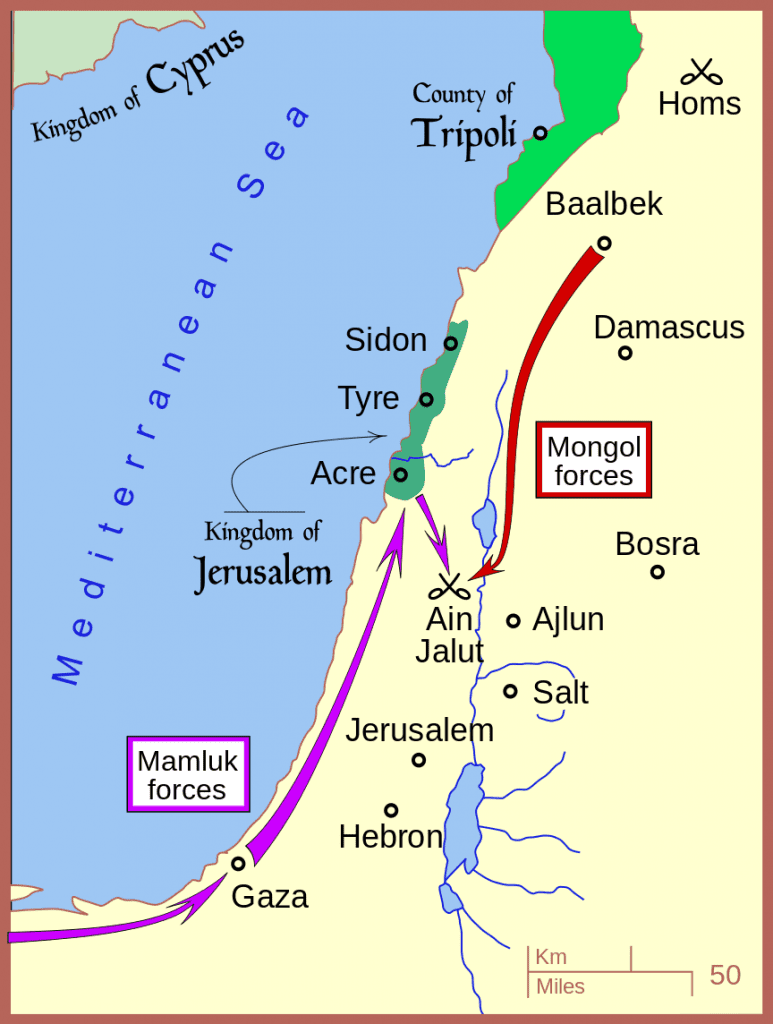

Finally, in 1260, the Mamluks of Egypt stopped the Mongol military advance at a place called Ayn Jalut[1], in Palestine. This must have been an immense shock to the Mongols. No army or city had ever successfully resisted them before. It required a group of central Asian warriors much like themselves to resist them now. Yet, although the Mamluks never receive any credit for this victory in most world history textbooks, their heroism and effectiveness in putting a stop to the Mongols has to be ranked as one of the crucial battles in human history. The invaders had advanced all the way from China, and there is no telling how far they might have gone had a group of unappreciated Muslims not stopped them in Palestine.

[1] Pronounced “Ayn Jah-LOOT,” this phrase means “Goliath’s Spring.” In Hebrew, the spring is known as En Harod. It was the site not only of the great medieval victory over the Mongols but, many centuries earlier, of the famous story told in Judges 7.

Posted from St. George, Utah