I spent a significant portion of the forenoon in a small meeting with Rabbi Dr. Alon Goshen-Gottstein, the founder and director of the Elijah Interfaith Institute in Jerusalem:

Rabbi Goshen-Gottstein is a distinguished scholar and an extremely prominent participant in interfaith dialogue, and it was a very interesting conversation. He has some interesting plans and goals, and I’m happy to be considered for inclusion in them.

In that context, I want to mention an extraordinary organization with which I’ve been somewhat involved over the years, called the Foundation for Religious Diplomacy.

What I really like about FRD is its commitment not to ecumenism, and not even merely to interfaith dialogue, but to what its founder, my friend Randy Paul (who was there at the Alta Club this morning), calls “respectful contestation.”

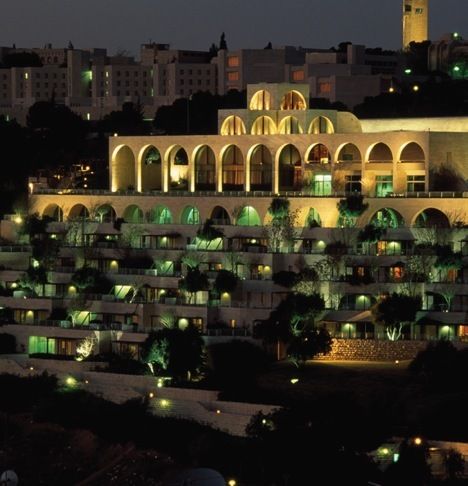

I’ve participated in numerous interfaith dialogues. Two that stand out in my memory, not altogether positively, took place Graz, Austria, in 1993, and in Jerusalem, Israel, in 1994.

They were billed as “trialogues” between Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

I was very impressed with the Jewish and Muslim participants, but rather less so with some of the Christians, who seemed to me to believe little or nothing and certainly little or nothing that was distinctively Christian.

It was very easy for such Christians to reach agreement with their Jewish and Muslim interlocutors, but also, or so it seemed from my perspective, essentially pointless. They didn’t represent anybody but themselves, and their concessions and understandings would carry no weight whatever with the communities they purportedly represented. (One or two of the Jewish and Muslim participants grew visibly frustrated with the talks as they went on, for precisely those reasons.)

I recall one evening presentation given in Graz to the general community by one of the participants in our small daytime discussions, a very prominent theologian from Harvard Divinity School.

He had, it seemed, once been a believer, but it was difficult by this point to discern what kind of faith, if any, he still had. And during his evening lecture, which was intended to serve as a peace offering or olive branch to the Austrian-resident Muslims in his audience, whom he obviously presumed to be offended by Christian belief, he essentially abandoned and apologized for every distinctive tenet of Christianity.

He plainly thought that they would be won over by his preemptive surrender, but they weren’t at all. In fact, they were very upset with him. During the question-and-answer session that followed his remarks, he received several stern tongue-lashings from leaders of the Muslim community in that part of Austria — businesspeople mostly, not trained theologians or imams — admonishing him on what they saw as his disrespect for revelation, for God, and for Jesus.

It was, actually, a very painful evening, but not even slightly surprising to me. I knew that they wouldn’t warm up to his essentially agnostic take on the three Abrahamic religions.

I also recall having to defend the Pope on several occasions during the meetings in Jerusalem, against attacks from two of the Catholic representatives in the “trialogue.” And, at the conclusion of those meetings, when I suggested that it would be very good, in the future, to include one or two academically-sophisticated Protestant conservatives among our number — I wanted to say “actual Christian believers” — one of those Catholics guffawed at the idea: “Intelligent Evangelicals?” he snorted. “That’s like a square circle.”

Anyway, FRD proceeds on the assumption that what’s really needed is to get the most committed members of various religious communities — including secularists and atheists — to converse respectfully with each other. Not as if their respective faith claims don’t matter, but precisely because they do. This is obviously more difficult than getting the most liberal members of the various communities to talk among themselves, but the results, if such discussions are successful in creating better mutual understanding and good will, are almost certain to be far, far more significant.