Proceeding with my notes from Daniel Johnson, “‘Hard’ Evidence of Ancient American Horses,” BYU Studies Quarterly 54/3 (2015): 162-164:

As of 2015, the scholarly consensus was that all “native” horses in the Americas must have descended from European stock, mostly Spanish and Portuguese, mostly strays. However, Daniel Johnson observes, the evidence for this is weak. Indeed, it seems to be mostly supposition. As a matter of fact, historical records seem to lean in the opposite direction. Spanish cavalry personnel kept close track of their imported (and limited) equine resources. In order for the stray hypothesis to work, too, both stallions and mares need to escape more or less together, etc.

Has this happened from time to time? Of course. Is it enough to account for widespread Amerindian horse culture within mere decades of First Contact? That is much less clear.

Actual historical information is available, not just vague mist. A look at four important early Spanish land expeditions involving horses is instructive:

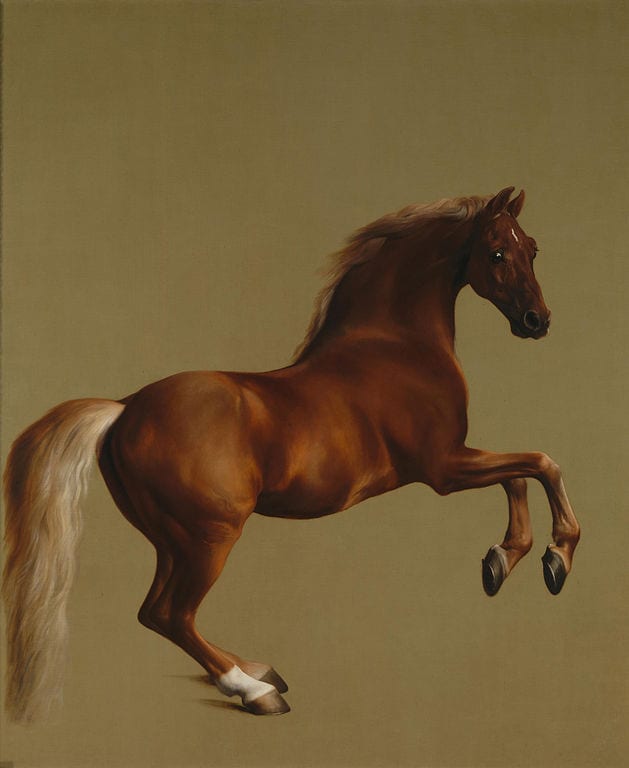

- When Hernán Cortés brought the first Spanish horses to the American mainland in 1519, he had only sixteen with him. Six of them were mares. (More on the Cortés expedition later.)

- The expedition led by the Spanish conquistador Pánfilo de Narváez left Cuba in 1528 with eighty horses aboard his ships. By the time he reached Florida after a windy and indirect voyage, only forty-two horses still survived. Five months later, all but one of those horses had died in battle or been eaten. A solitary animal, though, would be of little use in engendering a population of horses.

- It used to be believed that all American horses west of the lower Mississippi descended from horses discarded by Hernando de Soto’s men in 1541. However, says Johnson, “That assertion now rests firmly in the realm of fiction” (163). De Soto left Cuba with 243 horses in 1539. Twenty died at sea, so, when he arrived on the mainland, he had only 223 left. By 1542, only forty remained alive. In 1543, twenty-two of those horses left with De Soto’s men for the lower Mississippi River. But the remainder also came along, in the form of jerky. When, Hernando de Soto having died, the expedition was preparing to return to Cuba, De Soto’s successor, Luis de Moscoso Alvarado, had only four or five horses left. All of them were stallions. They were left behind, and the Spanish account relates that they were all killed by native tribes before the Spanish boats were out of sight.

- Francisco Coronado had 558 horses with him for his 1540 expedition into what is today the American Southwest — 556 caballos (“horses”) and two specifically identified as yeguas (“mares”).

To be continued.