(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

A brief article in the January/February 2015 issue of the Biblical Archaeology Review reported on an exhibit that had just concluded at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, entitled In Remembrance of Me: Feasting with the Dead in the Ancient Middle East.

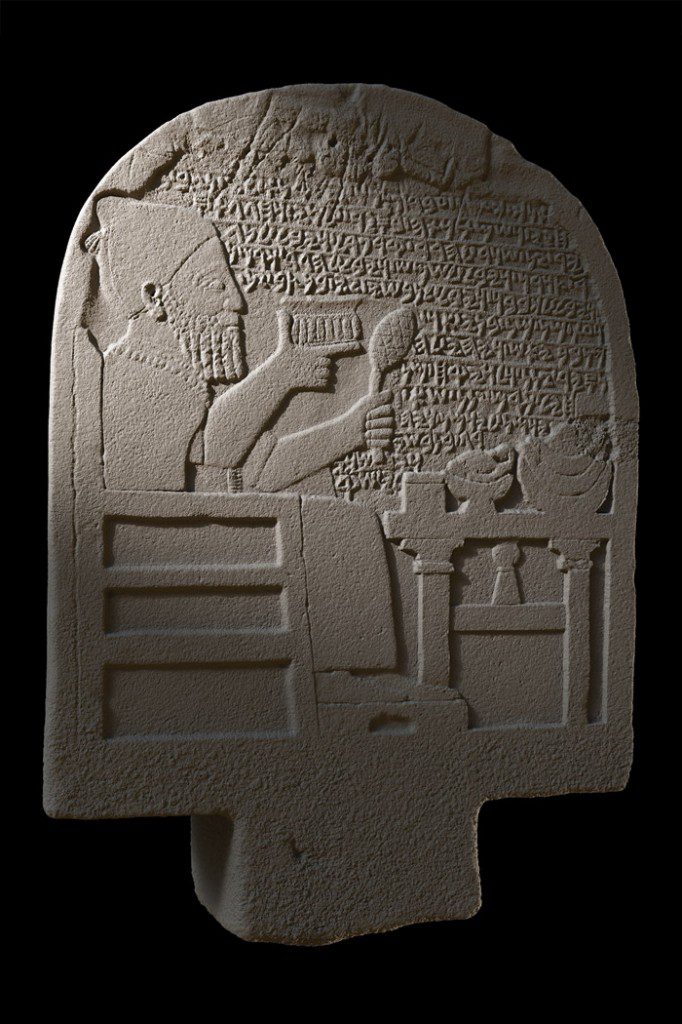

The artifact most prominently featured in the exhibit was the Katumuwa Stela, a basalt slab set up more than 2700 years ago in what is now southeastern Turkey, to memorialize a man named, unsurprisingly, Katumuwa.

The Aramaic inscription on the monument provides detailed instructions concerning feasts to be held in his memory after his death. His soul, the stela says, will reside in the slab itself and will participate in these feasts.

“The essential thing,” writes Virginia Hermann, one of the co-curators of the exhibit in the catalogue that accompanied it, “was not to be forgotten by the living, especially by your own family.”

“People who had the financial resources,” comments the Biblical Archaeology Review (“M.S.,” the author, is presumably Megan Sauter, BAR‘s assistant editor), “did everything possible to make sure that they would not be forgotten by the living.”

Evidence has been found for such feasts for and “with” the dead through the Levant, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, and the idea may survive in such festivals as the Dia de los Muertos in Mexico and the Qingming Festival in China.

But, of course, the dead are almost all soon forgotten anyway. The poor, lacking monuments, are forgotten soon, but even Katumuwa, who plainly had enough money to commission an inscribed and illustrated basalt monument standing more than three feet tall, has been essentially forgotten for nearly three millennia. (His stela was discovered by archaeologists only in 2008.)

Mortal efforts to transcend death are inevitably pathetic and futile. We still bury treasures in the grave with our loved ones and we still lay flowers on their graves, but, without God, we have no real hope.

The Muslim prophet Muhammad had only one son, Ibrahim, and that son died as an infant. With others, Muhammad carried Ibrahim’s body to a nearby cemetery, where, after a prayer, the tiny boy was lowered into a grave. Muhammad himself carefully filled the hole with sand, lovingly sprinkled some water upon his son’s burial place, and then marked the grave with a stone. “Tombstones,” he remarked, half speaking to himself, “do neither good nor harm. But they make the living feel a bit better.”

Thankfully, we aren’t left alone in such situations. Mercifully, our sadly inadequate human efforts don’t represent the last word regarding death.