I’ve just finished reading Nina Strochlic, “The Abduction of 276 Nigerian Schoolgirls Outraged the World. 112 Are Still Missing. The Survivors are Reclaiming Their Future,” National Geographic (March 2020): 84-97. It’s a reminder of the horrible story that began at about 11:00 PM on 14 April 2014, when truckloads of Islamist militants from the Boko Haram terrorist group invaded the village of Chibok, in northeastern Nigeria.

The Government Secondary School for girls in Chibok had just reopened for final examinations. Less than half of the girls of the region attend even primary school, so these secondary school girls were doing unusually well.

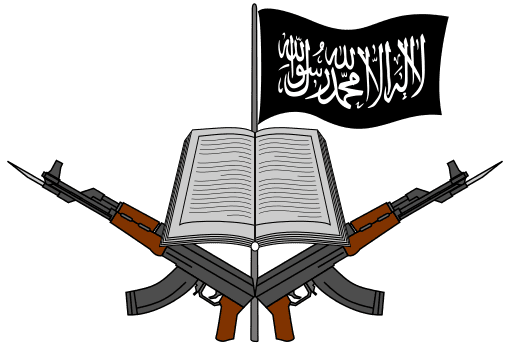

But that displeased the brutal loons of Boko Haram, a group the title of which means something roughly like “Western education is forbidden” or even “Western influence is a sin.” So they drove into the village, forced 276 of the girls from their dorms into trucks, and headed for the Sambisa Forest Preserve, even further to the northeast. There, the militants gave them a stark choice: Convert to Islam and marry or, alternatively, become slaves. Reportedly, most chose slavery.

Of those 276 abducted Chibok girls, 112 are still missing. Some of those who remain missing are presumed dead. Those who are free either escaped somehow or were released in exchange for government cash or as part of prisoner exchanges. Most spent nearly three years as captives of Boko Haram.

More than a hundred survivors are now studying at the American University of Nigeria in Yola, roughly two hundred kilometers almost due south of Chibok. The photographs that accompany Nina Strochlic’s article in National Geographic, taken by the French photographer Bénédicte Kurzen, show women of, in some cases, striking beauty and dignity. (I dare say that because my wife made the observation to me in the first instance.)

Boko Haram promised to kill them if they returned to school, so guards watch over their building and follow them whenever they leave it. Some of them still bear shrapnel and bullets in their bodies. One of them walks with a cane, while another has an artificial leg. As might easily be imagined, many of them were traumatized by their experience, so a “24/7 support system” has been made available to them, including eleven student affairs “aunties” who actually live in the dormitories with them, a specially assigned nurse, and a walk-in psychologist’s office.

Writes Strochlic,

Not all the survivors of Boko Haram’s war have such opportunities. In Borno State, the epicenter of the crisis, classes were canceled for two years. There and in two neighboring states, roughly 500 schools have been destroyed, 800 are closed, and more than 2,000 teachers have been killed.

Fifteen miles from AUN’s campus, Gloria Abuya gets up at 5 a.m. and walks two hours to school from the 2,100-person camp for displaced people where she lives. When Boko Haram militants first arrived in Gloria’s hometown of Gyoza in 2014, they killed the men and ordered their wives to bury the bodies. Later, they took the girls. Gloria spent two months in captivity before escaping one night as her captors prayed. (95)

It’s a terribly sad story, both in terms of the pain and suffering that Boko Haram’s evil vision has imposed upon innocent young girls and their families and in terms of the damage that it has done to education in Nigeria, which badly needs better schooling for its people.