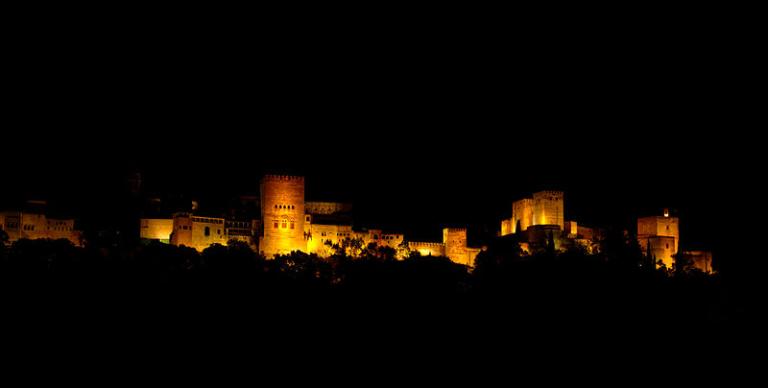

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photograph)

I sometimes need to remind a few of my critics that I’m paid to profess Arabic and Islamic studies, not to do apologetics. That’s always been the case, and it remains so still today.

For instance, I have just, within the past few minutes, finished grading a stack of student papers from my course on the Humanities of Islam, which focuses principally on literature, art, and architecture.

Now, though, I need to get ready for tomorrow’s classes. (No rest for the wicked! And who, those critics might be inclined to point out, could possibly deserve rest, by that standard, less than I do?)

In my class on Islamic philosophy, we’re reading Lenn Evan Goodman’s translation of the twelfth-century Arabic allegorical philosophical novel Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān (حي بن يقظان, Alive, son of Awake) — also known, in Latin, as the Philosophus Autodidactus — that was written by the Andalusian or Iberian philosopher Ibn Tufayl (Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Muḥammad ibn Tufayl al-Qaysī al-Andalusī; ca. 1105-1185).

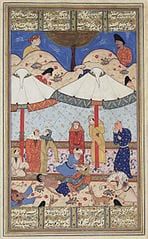

(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

In my Humanities of Islam class, we’ve just finished reading a translation of the twelfth-century Persian poem Layla and Majnun (لیلی و مجنون; Leyli o Majnun), which was composed by Niẓāmī Ganjavī as the third part of his Khamsa (خمسه, “Quintet”) or Panj Ganj (پنج گنج, “Five Treasures”). George Gordon Lord Byron is said to have pronounced it “the Romeo and Juliet of the East,” and the strong resemblance between the two stories is obvious. Now, though, we’re on to reading the Arabian Nights — which are definitely not childrens’ stories.

In my course on classical Arabic literature, we’re currently working through the opening portion of The Reformation of Morals, a treatise on ethics and the development of character by the Syriac Jacobite Christian philosopher Yahya ibn Adi (that’s Abū Zakarīyā’ Yaḥyá ibn ʿAdī, who lived in Iraq AD 893–974). I’ve never taught it before, and I fear that the students are finding it a bit difficult. We may need to adjust things a little, or even find a less technical reading.