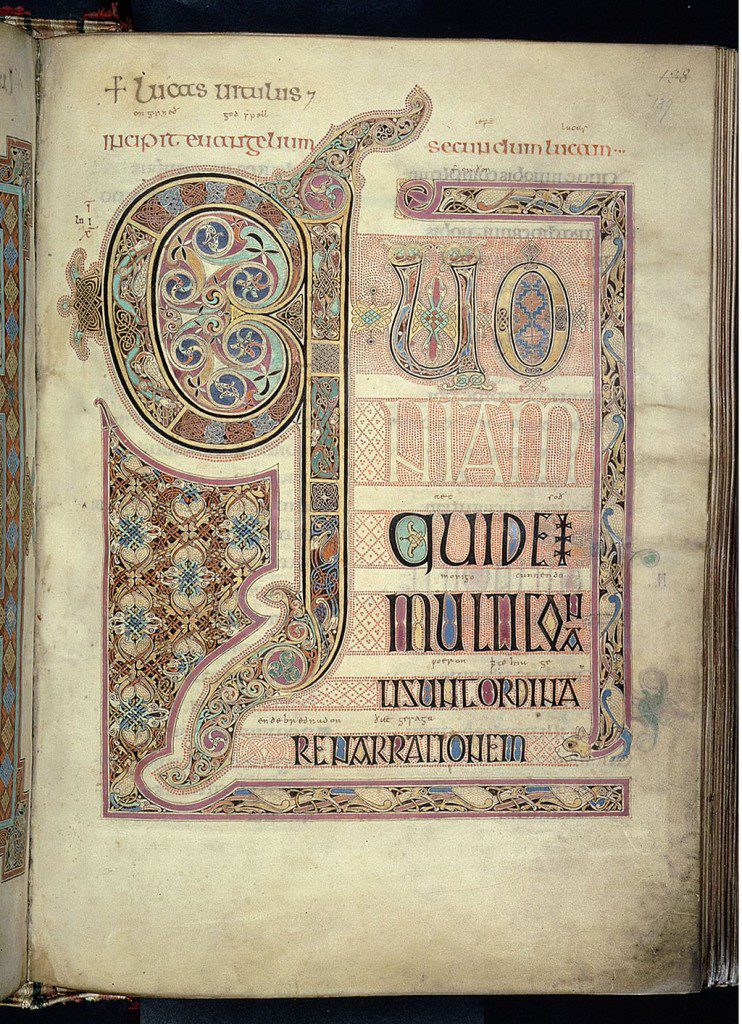

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

I offer here a summary passage from Mark D. Roberts, Can We Trust the Gospels?: Investigating the Reliability of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Books, 2007). Roberts, who, at the time his book was published, was senior pastor at Irvine Presbyterian Church in southern California, earned a Ph.D. in New Testament studies from Harvard University. In the quotation that I cite below, Rev. Roberts refers to Q (which stands for German Quelle, meaning “source”), a hypothesized written collection of logia or sayings of Jesus, purportedly drawn from the oral tradition of the early Christian movement. Q is conceived as part of the material common to both the Gospels of Matthew and Luke but not found in the Gospel of Mark:

In my first New Testament class in college, I learned about a relatively new scholarly discipline called redaction criticism (from the German term Redaktionsgeschichte, meaning “the history of editing” of the Gospels). Redaction critics, assuming that Matthew and Luke used Mark and Q as sources, studied the editorial changes made by Matthew and Luke. These changes revealed the distinctive theologies of their Gospels. I say “distinctive.” What I heard in class, however, was “distinctive and contradictory.” In that religion class, and throughout my graduate studies in New Testament, it was popular to emphasize the unique perspectives of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and to minimize what they had in common, or even to deny that they had much in common at all. I heard plenty about the “contradictions” between the Gospels as my professors engaged in redaction criticism.

Some conservative scholars reacted negatively to redaction criticism, even suggesting that the discipline itself was inconsistent with biblical authority. But most evangelical scholars have come to see both the good and the bad in redaction criticism. The good has been identifying the distinctive efforts of the Gospel writers, who didn’t merely collect material and paste it together, but who carefully wove that material into a coherent and creative narrative. Redaction criticism has raised the respect given to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John as creative, careful writers, and not mere collectors of traditions.

The bad part of redaction criticism has been the tendency of many who use this methodology to exaggerate the differences among the Gospels. Nobody doubts that there are such differences and that they are significant. But sometimes in focusing so much on the different trees one loses sight of the common forest. Think for a moment. If you were to sit down and read Mark, and then Matthew, do you think you would come away thinking, Now there are two unique, virtually incompatible pictures of Jesus? Hardly! In fact, I think you would be more inclined to say, after reading Matthew, Well, he adds some more fascinating material (like the visit of the Magi or the Sermon on the Mount) but that’s mostly the same story as I found in Mark. It was rather redundant in parts, actually. (96-97, italics in original)