(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

Scientism, in at least some of its manifestations, is the close cousin or sibling if not indeed altogether the Doppelgänger of the once-fashionable form(s) of philosophy known as logical positivism, logical empiricism, and/or neopositivism.

Very popular, especially in Europe, in the 1920s and 1930s, logical positivism, as I’ll call it here, argued that only statements that can be verified through empirical observation can be regarded as “significant” or genuinely meaningful. Statements regarding “unobservables” — and there is a vast host of such unobservables, some of them really quite important — were to be regarded as expressions of hope or preference, or as metaphorical, or, less charitably but not uncommonly, as “nonsense.”

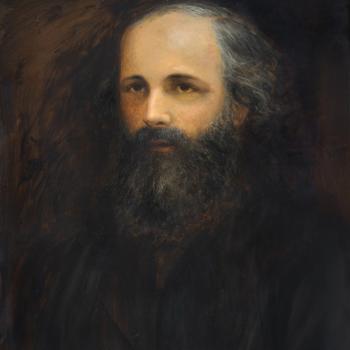

Prominent groups of philosophers, engineers, scientists, and mathematicians, especially those associated with the so-called Berlin Circle (“led” most prominently by Hans Reichenbach) and the Vienna Circle (most notably including Moritz Schlick, but also Rudolf Carnap, Hans Hahn, Otto Neurath, and eventually Carl Hempel, with Karl Popper as their persistent, friendly, in-house dissenter and critic), were seeking to establish philosophy as a science-based discipline, freed from such matters as metaphysics and (certainly for some, at least) theology, where no empirical proof was available — definitely no decisive empirical proof — and, thus, where arguments have gone on and on for centuries and are likely to continue forever, this side of the veil of death anyway, without clear, objective resolution.

There’s at least one pretty obvious problem at the base of the enterprise, though: The proposition that only statements verifiable through empirical observation should be regarded as “significant” or genuinely meaningful is, itself, not strictly verifiable through empirical observation.

***

In my experience, a surprisingly high number of those devoted to scientism are not only not themselves scientists but are relatively unfamiliar with current science. I first noticed this phenomenon many years ago, when I was attempting to counsel a young man who had lost his faith because, he said, science had proven that God was impossible. I at first assumed that he was a science major. But he was not. He was a history major. I asked him whether he had ever taken a course on the history of science. He had not. And his grasp of physics was, so far as I could tell, vaguely and naïvely Newtonian. Classical. It was actually difficult to discuss scientific issues with him because he was too uninformed to sustain a serious conversation about them.

But current science, in at least some areas, is revealing a universe to us that is downright weird. Take this, for example:

“Quantum paradox points to shaky foundations of reality”