(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Newly posted today on the website of the Interpreter Foundation, the introduction (by Daniel C. Peterson) to Volume 39 of Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship:

“Reckoning with the Mortally Inevitable”

Abstract: Every human enterprise — even the best, including science and scholarship — is marred by human weakness, by our inescapable biases, incapacities, limitations, preconceptions, and sometimes, yes, sins. It is a legacy of the Fall. With this in mind, we should approach even the greatest scientific, cultural, and academic achievements with both grateful appreciation and humility. J. B. Phillips’s rendition of Paul’s words at 1 Corinthians 13:12 captures the thought nicely: “At present we are men looking at puzzling reflections in a mirror. The time will come when we shall see reality whole and face to face! At present all I know is a little fraction of the truth, but the time will come when I shall know it as fully as God now knows me!”

***

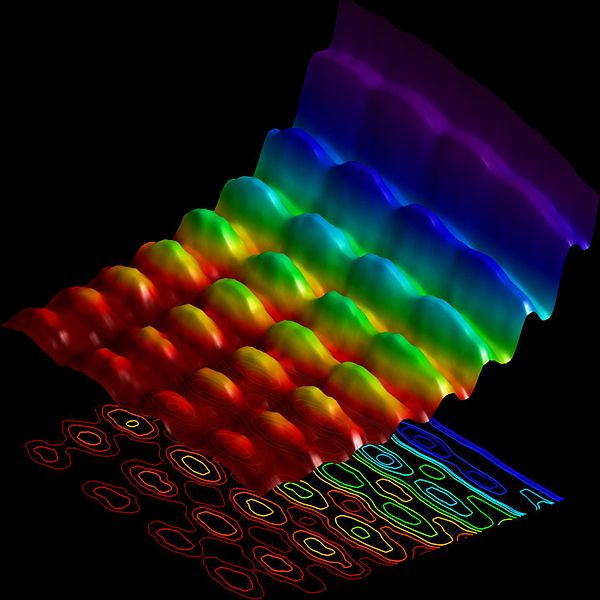

Chapter 4 (“Quanta,” pages 91-121) of Carlo Rovelli, Reality Is Not What It Seems: The Journey to Quantum Gravity, translated by Simon Carnell and Erica Segre (Penguin, 2017), is an unusually lucid history and conceptual summary of quantum theory — although, given the very nature of its subject matter, it’s still more than a little bit mind-stretching.

Rovelli, an Italian theoretical physicist currently based in Marseilles, France, boils quantum theory down to three essential features: granularity, indeterminacy, and relationality. Toward the end, though, he steps back and turns to his audience:

Certainly, quantum mechanics is a triumph of efficacy. And yet . . . are you sure, dear reader, that you have fully understood what quantum mechanics reveals to us? An electron is nowhere when it is not interacting . . . mmm . . . things only exist by jumping from one interaction to another . . . well . . . Does it all seem a little absurd?

It seemed absurd to Einstein.

On the one hand, Einstein proposed Werner Heisenberg and Paul Dirac for the Nobel Prize, recognizing that they had understood something fundamental about the world. On the other, he took every opportunity to grumble that, however, none of this made much sense.

The young lions of the Copenhagen group were dismayed: how could this come from Einstein himself? Their spiritual father, the man who had the courage to think the unthinkable, now pulled back and feared this new leap into the unknown — the very leap which he had himself triggered. How could this be that the same Einstein, who had taught us that time is not universal and that space bends, was now saying that the world could not be this strange?

Niels Bohr patiently explained the new ideas to Einstein. Einstein objected. Bohr, in the end, always managed to find answers to the objections. The dialogue continued for years, by way of lectures, letters, articles . . .

Einstein did not want to relent on what for him was the key point: the notion that there is an objective reality, independent of whatever interacted with what. He refused to accept the relational aspect of the theory, the fact that things manifest themselves only through interactions. (117-118, 119)

Niels Bohr — according to Rovelli, Albert Einstein’s greatest rival or opponent — gave Einstein a moving tribute when Einstein died. And then, when Bohr himself died a few years later, somebody took a photograph of the blackboard in his office. On it, to the very last, he was still trying to respond to Einstein’s objections to quantum theory.