The Period of the Gunpowder Empires (1500-1800)

As might be guessed from Hodgson’s title for this period, the important fact about the time was gunpowder. This new technology, borrowed from the West (but, ultimately, from China), allowed the existence of greater states and thus permitted greater centralization of power. Putting it less abstractly, the states that adopted the new military technology gobbled up the states that did not. What marks the period, then, is a partial recovery from the political fragmentation that was the special characteristic of the Middle Periods. But if that seems like a healthy development for the Muslims, it should be remembered that the period also saw the beginning of the spectacular rise of the West and its expansion in every direction. Muslim rulers were not aware of it yet, but their states were headed for turmoil.

Three notable Islamic empires flourished during the “Gunpowder Period.” These were the Mogul or Mughal Empire in India, the Safavid Empire in Persia, and the Ottoman Empire in the remainder of the Islamic world. I shall have something to say about each one of these.

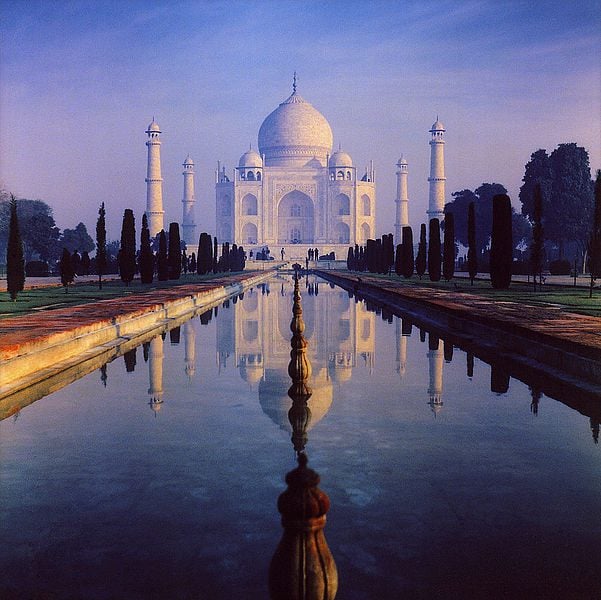

As their name indicates, the Mughal or Mogul dynasty derived from Mongol stock, converted to the religion of Islam. They ruled most of India and Afghanistan during the 1500s and 1600s. The most glorious of their sultans was the great city-builder and patron of the arts Akbar the Great, who reigned from 1556 to 1605 and was thus a contemporary of Queen Elizabeth of England. But the best known fact about the Mughals in the West is unquestionably the building of the beautiful Taj Mahal, one of the world’s finest pieces of architecture, during the reign of Shah Jahan (1627-1658).

[Add some detail here on the Taj Mahal]

Early in the 1700s, the empire began to break up. Nevertheless, the Mughals continued to rule a small kingdom centered in the city of Delhi until the British conquest of India in the nineteenth century. It is worth stopping for a moment to consider the remarkable fact that the British were able to complete so stunning an achievement, to reflect that we are tempted simply to say “the British conquest of India” without being properly astonished at the improbability of it. Yet it is amazing to realize that the small island nation of Great Britain — controlled by the even smaller place called England — was able to conquer the entire Indian subcontinent, thousands of miles away, and to hold it for a long period of time. That they were able to do so is yet another example of the fact that disunity invites conquest. If the Indians had been united and the Mughal Empire intact, the British could never have dreamed of controlling that vast nation.

The Safavis, a Turkish tribe, gained control over areas of Iran in the late 1400s and early 1500s. But the official beginning of the Safavid Empire must be placed in the year 1501, when the tribe’s leader, Ismail Safavi, was crowned shah, or king. It is the Safavids who made Iran a Shiite nation and linked Shiism with the Persians in a firm bond that has never been challenged in the intervening centuries. In the nineteenth century, it was sometimes suggested that Persian Shiism reflected something innate in the Persian soul, a natural Indo-European reaction against Semitic Islam, as embodied in Sunnism. (Such belief in what might be called “racial essentialism” or even “race as destiny” was not unconnected with what eventually turned into the Nazi vision of Aryan or Indo-European supremacy — and its nightmarish genocidal extermination camps.)

The greatest ruler of the Safavid dynasty was Shah Abbas, who reigned between 1587 and 1629 and was thus himself a younger contemporary of Elizabeth I. He and his successors strongly supported architecture and the other arts, and—something that is considerably more rare—showed remarkably good taste in doing so. The blue and gold mosques of Iran, the Persian miniature paintings that were used to illustrate books of the period, and the magnificent carpets produced by the country’s craftsmen all testify to the remarkable legacy of civilization given to the world by Iran. In 1598, Shah Abbas made the city of Isfahan his capital and devoted himself to planning parks and mosques and large public squares. It rapidly became known as one of the world’s most beautiful cities. But beauty does not abide forever. In 1722, little more than a century after Shah Abbas, fierce Afghan armies invaded Iran and conquered the city, putting an end to the Safavid dynasty.

The most enduring Gunpowder Period state, however, was the Ottoman Empire. It began somewhere around the year 1300, and at least limped on until 1922. In the 1500s and 1600s, it was far and away the most powerful empire in the world; at its height it held not only Anatolia (modern Turkey) but also southwest Asia (Syria, Palestine, part of Iraq, the Arabian Peninsula), southeast Europe (including Greece and the Balkans), Egypt, and much of North Africa. The walls of the present-day Old City of Jerusalem–often mistaken by tourists for the long-gone walls of the biblical period–were actually built by its Turkish imperial masters.

The Ottomans were originally nomadic Turkic tribes from Central Asia who had been enlisted, as many Turks had been, to help fight the “infidel” Byzantines. They converted to Sunni Islam, as Turks generally did, and indeed became truly fearsome border warriors. But they soon realized that they could also fight on their own behalf. So why not carve out their own state? Their founder and first sultan was a man named Osman.[1] He inaugurated a series of successful rulers that, for sheer consistency of ability, has little parallel anywhere in world history. One of the first notable achievements of the Ottomans was the conquest of the city of Bursa in Anatolia (Asia Minor, or contemporary Turkey) in the year 1326. Bursa would serve as their capital until the conquest of Constantinople in the fifteenth century, and they adorned it with notable and distinctive buildings. But Ottoman expansion came at the expense of the Byzantines in Anatolia. This is not surprising, of course. It was their duty and their reason for having been brought to the region in the first place. Their efforts culminated in the seizure of Constantinople in 1453 and the collapse of the Byzantine Empire. From this point on, there was no Byzantine Empire left to fight, so the holy warriors of the Ottoman Empire turned their cannons and their muskets to the East, against their fellow Muslims.

But before we speak of the significant Ottoman impact on the Arab world, another of their opponents merits brief mention if only because he is famous in the West. It is a peculiar fame. Very few Westerners have any idea who this person really was, and many would not even recognize his title. He seems almost to have been a particular obsession of Mehmet II, the Conqueror, the man who had succeeded in taking Constantinople after centuries of Muslim daydreaming and failed attempts. Mehmet was never able to put an end to this man, who tormented him for years and finally died peacefully in bed. The man’s name was Vlad Tepish. He lived in a region known as Transylvania, or modern Romania. Vlad was also known as Vlad Dracul, “Vlad the Impaler,” because he had the endearing habit of impaling captured enemies on stakes. The legend of “Dracula”—or that portion of it that was not invented in Hollywood (and a large part of the vampire legend was, in fact, devised by Hollywood screenwriters)—seems to be derived from this cruel man.

For a long time after 1453, most Ottoman opponents were Muslim. (Certainly there were more Muslims than vampires.) In 1516, Syria fell to a successor of Mehmet II, a sultan known somewhat menacingly as Selim the Grim. The next year, 1517, saw the conquest of Egypt and the end of the Mamluks. One is almost inclined to pity them. They were, in a sense, prisoners of their own virtues. Their horseback heroism, so effective against the thirteenth-century Mongols, was pathetically (although perhaps nobly) out of date. When they defended Cairo against Selim’s armies, they took no cannons. They disdained artillery and firearms as beneath the dignity of a knight. And they were cut to shreds, as was anybody else who, for whatever reasons, failed to keep up with the times. Dignity and chivalry, as the armored knights of Europe also discovered, could not stand up to a peasant with a gun.

[1] This is the Turkish form of the Arabic name Uthman—the same as that of the third of the “rightly-guided caliphs” who succeeded the Prophet Muhammad—and it is from a distortion of his name that we derive the name of the empire itself, Ottoman.

Posted from Park City, Utah