(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

One reason for hoping that there is a life after death, a better world to come, is the deep human desire for justice. This can be regarded from at least two different angles. One is the wish to make things right. We’re naturally revolted by the thought that the murderer is permitted to write the last chapter in the life of his victim, that, for example — to be quite blunt about it — the last few moments of a child’s existence might be focused on the horrifying, hopeless, painful, and, in a sense, utterly solitary experience of rape and strangulation. We want the story to end happily. We don’t want Stalin and the Gulag, the Cambodian “killing fields,” or Hitler’s death camps to have the last word. This scarcely proves that the human soul is immortal, but it does demonstrate, I think, that a hope for immortality can be motivated by factors other than the mere personal fear of death.

I want to concentrate here, though, on the desire for cosmic justice. This shouldn’t be confused with a lust for vengeance or retribution. It may overlap with that, but it’s quite distinct. (More on that later.)

There are, simply, or so it seems to me, certain humanly-committed evils that are so egregious, so awful in their scope, that no earthly punishment really suffices to satisfy our sense of justice. Consider serial killers, for example. Many of them have tortured and killed dozens, even scores, of victims. One is believed to have murdered as many as 250 people. Several others are in that vicinity. No number of years in prison, no single death (whether by painless lethal injection or hydrogen cyanide in a gas chamber or by firing squad or hanging) seems really commensurate with what such criminals have done. Even those who approve of capital punishment, hearing of their deaths, must inevitably shrug their shoulders, unsatisfied. Something seems lacking. Justice has perhaps been done. But, in another sense, justice has not been done, and cannot have been done. Not fully.

When Hermann Göring took cyanide at Nuremberg shortly before he was to be hanged for his crimes, many (probably including himself) felt that he had cheated justice. Hitler’s suicide in that Berlin bunker was, many thought, too quick and easy. Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin and Fidel Castro died in their beds, essentially of old age. Saddam Hussein’s execution seemed inadequate recompense for his gassing of Kurdish villages, putting political enemies into wood chippers, and myriads of other such crimes.

I cite here some thoughts of the prominent Austrian-American sociologist Peter Berger (1929-2017), from his book A Rumor of Angels (New York: Anchor Books, 1969):

Berger contended that there are cases “in which our sense of what is humanly permissible is so fundamentally outraged that the only adequate response to the offense as well as to the offender seems to be a curse of supernatural dimensions” (65).

We want a condemnation that is “absolute and certain,” not hesitant or qualified but with “the status of a necessary and universal truth” (67). This moral judgment may take into account political, psychological, historical, and economic factors that went into what happened, but it cannot in the end be tentative, as human judgments typically are. In cases of common human judgment, Berger wrote,

We are . . . faced with a simple alternative: Either we deny that there is here anything that can be called truth — a choice that would make us deny what we experience most profoundly in our own being — or we must look beyond the reality of our “natural” experience for a validation of our certainty. (67)

In other words, Berger seems to be saying, our hearts cry out for transcendent, supermundane, even divine justice.

“Deeds that cry out to heaven,” he writes, “also cry out for hell. . . . [T]he doer [of evil] not only puts himself outside the community of men; he also separates himself in a final way from a moral order that transcends the human community, and thus invokes a retribution that is more than human.” (67-68).

Now, I don’t know that Professor Berger would have agreed with me in what I’m about to say, but here it goes anyway:

I’m not sure that our souls demand unending torture in Hell for egregious wrong doers before they’ll be satisfied. I don’t think that mine does. What we demand at a minimum, though, or so it seems to me, is a genuine and genuinely sorrowful acknowledgment by the wrongdoer of the pain and injury that he or she has caused. Not simply a painless slipping away without having ever come to terms with it.

I’ve already hinted that I’m a cautiously hopeful quasi-universalist. I repeat, once again, the response of the late Pope St. John Paul II to the question of whether a Christian must believe in Hell. Yes, he said, Christians are obliged to believe in Hell. “But we can hope that it might be empty.”

I take comfort in reports from near-death experiencers of the “life review” that they undergo, during which they witness a three-dimensional “playback” of the actions of their lives in the presence of a loving guide who seeks to encourage their learning from it. They recount that they could feel the pain that they had caused others. (Imagine how horrible such a “life review” would be for a Hitler or a Genghis Khan or an Attila the Hun! You want them to experience Hell? That would be Hell.) But they also say that the purpose of the exercise was to help them to understand and to grow. I like to think that even the worst might someday have a shot — perhaps, it’s true, after untold eons — of finding wholeness and forgiveness and of moving forward. But there is no “cheap grace,” to borrow Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s phrase. It’s not a matter of simply mouthing the words “I’m sorry.” True penitence is required. And that, I think, is what we both hope for ourselves and wish from others.

***

Sigh. Yet another article has appeared in Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship. This one is by Professor Donald W. Parry. It is perhaps yet another sign that, as one critic has astutely observed, the energy and productivity of the Interpreter Foundation are palpably fading:

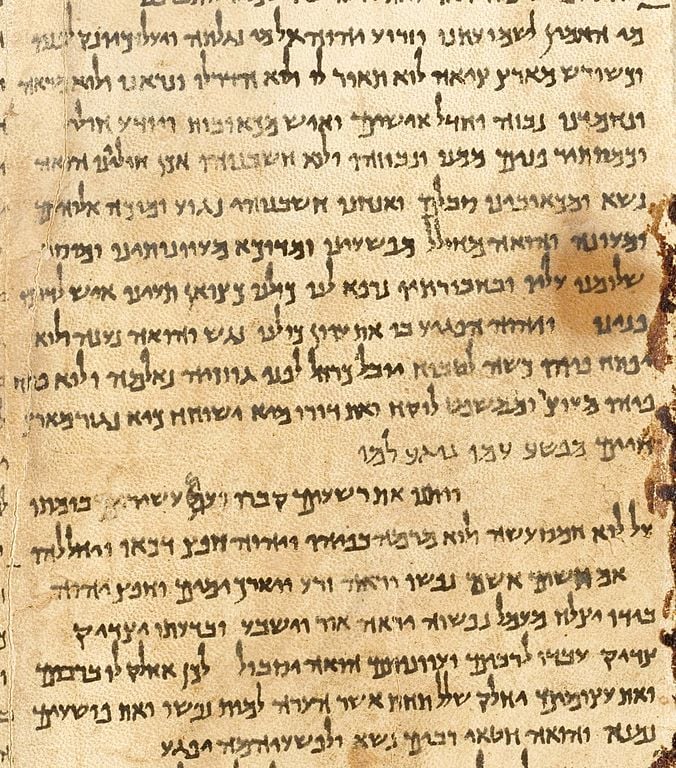

“The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaA)—Catalogue of Textual Variants”

Abstract: In this erudite survey of textual variants in the “Great Isaiah Scroll” from Qumran, Donald W. Parry lays out the major categories of these differences with illustrative examples. This significant description of the most significant book of Old Testament prophecy provides ample evidence of Parry’s conclusion that the “Great Isaiah Scroll” “sets forth such a wide diversity and assortment of textual variants that [it] is indeed a catalogue, as it were, for textual criticism.”

[Editor’s Note: Part of our book chapter reprint series, this article is reprinted here as a service to the LDS community. Original pagination and page numbers have necessarily changed, otherwise the reprint has the same content as the original.

See Donald W. Parry, “The Great Isaiah Scroll (1QIsaa)—Catalogue of Textual Variants,” in “To Seek the Law of the Lord”: Essays in Honor of John W. Welch, ed. Paul Y. Hoskisson and Daniel C. Peterson (Orem, UT: The Interpreter Foundation, 2017), 247–65. Further information at https://interpreterfoundation.org/books/to-seek-the-law-of-the-lord-essays-in-honor-of-john-w-welch-2/.]

Another sign of our sad decline was the appearance of this item on Saturday last:

Book of Moses Essays #29: Enoch’s Grand Vision: The Earth Shall Rest (Moses 7:60–69)