(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Many who deny an objective or divine foundation to morality nonetheless assume that evolutionary processes lead naturally, sociobiologically, to something broadly resembling a traditional Judeo-Christian ethic of mutual help, human rights, and cooperation. Thus, the religious underpinnings that some have thought necessary to morality can be safely dispensed with, as we climb inexorably onto the sunny uplands of naturalistic reason.

To me, however, this does not seem at all obvious or inevitable.

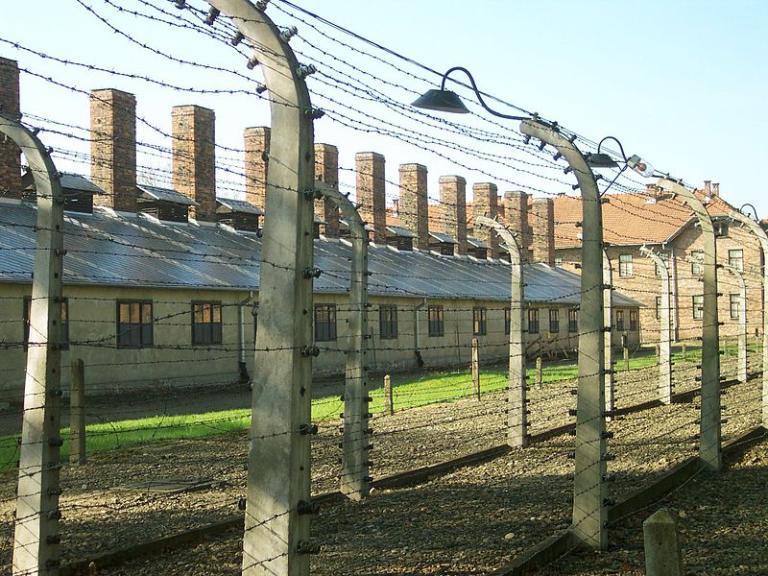

If there is no objective or divine basis for morality, the selection of moral values seems to be purely subjective, rather like preferring chocolate ice cream to vanilla, or tacos to tostadas. So, is it merely a subjective personal choice to prefer Corrie ten Boom’s concealment of Jews from the Third Reich over Josef Mengele’s experimenting on them in Auschwitz?

Note, too, that Dr. Mengele — who held doctorates in both medicine and anthropology — was promoted to the rank of Hauptsturmführer (roughly equivalent to Hauptmann or “captain” in the mainstream German army) for his work, while the ten Boom family were imprisoned as criminals for their efforts in the Dutch Underground, which are estimated to have saved roughly 800 lives: Corrie, imprisoned in the concentration camp at Ravensbrück, was freed by a clerical error. But the widowed father of the family, Casper ten Boom, died in Scheveningen Prison. His daughter Betsie died at Ravensbrück. His son Willem, a Dutch Reformed pastor, contracted spinal tuberculosis while imprisoned and died shortly after the end of the war. His grandson Christiaan, Willem’s son, died at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. If moral standards are set by societies, with no other basis, if they are effectively identical with codified law, should contemporary citizens of the German Reich have felt morally obliged to condemn the ten Booms as immoral criminals and to admire and celebrate Dr. Mengele? If not, why not?

And if we are entirely free to create our own morality, why choose one that favors kindness, honesty, and cooperation?

Douglas Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith (Downers Grove: IVP and Nottingham: Apollos, 2011), 343-344, draws on an 1845 book by Max Stirner (1806-1856), a little-known German “young Hegelian” philosopher and contemporary of Karl Marx, entitled The Ego and Its Own (New York: Libertarian Book Club, 1963). Stirner accused his fellow atheists of being “pious,” because, in holding to Christian moral precepts without underlying Christian belief, he felt they were being inconsistent (Stirner, 185). “All things are nothing to me,” he wrote. “I am nothing in the sense of emptiness, but I am the creative nothing, the nothing out of which I myself as creator create everything” (Stirner, 5)

You think that the ‘good cause’ must be my concern? What’s good, what’s bad? Why, I myself am my concern, and I am neither good nor bad. Neither has meaning for me. . . . Nothing is more to me than myself. (Stirner, 5)

I decide whether it is the right thing in me; there is no right outside me. (Stirner, 190)

I secure my freedom with regard to the world in the degree that I make the world my own . . . by whatever might, by that of persuasion, or petition, of categorical demand, yes even by hypocrisy, cheating, etc.; for the means that I use for it are determined by what I am. (Stirner, 165)

What I can get by force I get by force, and what I do not get by force I have no right to. (Stirner, 210)

I am entitled by myself to murder if I myself do not forbid it to myself, if I myself do not fear murder as a ‘wrong.’ (Stirner, 190)

(He apparently not only allowed murder as a moral option, but incest between brothers and sisters. [Stirner, 45-46, 190])

As long as you believe in the truth, you do not believe in yourself, and you are a — a servant, a — religious man. You alone are the truth, or rather, you are more than the truth, which is nothing before you. (Stirner, 353; odd punctuation in the original)

Groothuis raises the obvious question: “I wonder if Stirner expected his readers to take his statement as truth for them.”

Here is how Groothuis formulates this portion of his moral argument for God, as a reductio ad absurdum:

- Relativism leads to nihilism.

- Nihilism is morally unacceptable.

- Therefore, (a) relativism is morally unacceptable.

- Therefore, (b) we need another moral theory to support objective morality.

Now, a moral relativist may respond “So what? Max Stirner was an obscure outlier.” But, of course, his fame or lack thereof is perfectly irrelevant. The point is that Stirner was actually being, as a German speaker might say, durchaus konsequent — that is, thoroughly consistent, merely following his presuppositions to a logical conclusion. But I’ll give you a much more famous thinker as another example:

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is probably most generally notorious for his declaration “God is dead.” But he plainly saw what this entailed. He held the ideas of “a moral order of the universe”and of “sin” in utter contempt, as “lies” (27, 28). “The best way of leading mankind by the nose,” he writes, “is with morality!” (50) And he drew precisely on Darwinian evolution as a basis for his ethical viewpoint. Herewith, a sampler of quotations from Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist: A Criticism of Christianity [1888], translated by Anthony M. Ludovici (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2006), italics and punctuation in the original:

“Virtue,” “Duty,” “Goodness in itself,” goodness stamped with the character of impersonality and universal validity — these things are mere mental hallucinations. . . . The most fundamental laws of preservation and growth demand precisely the reverse, namely: — that each should discover his own virtue, his own Categorical Imperative. (10)

What is good? All that enhances the feeling of power, the Will to Power, and power itself in man. What is bad? — All that proceeds from weakness. What is happiness? The feeling that power is increasing, — that resistance has been overcome.

Not contentment, but more power; not peace at any price, but war; not virtue but efficiency [German Tüchtigkeit, “capability,” “competence” – dcp] (virtue in the Renaissance sense, virtù, free from all moralic acid). The weak and the botched shall perish: first principle of our humanity. And they ought even to be helped to perish.

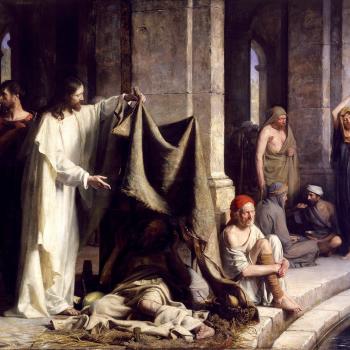

What is more harmful than any vice? — Practical sympathy with all the botched and weak — Christianity. (3)

Life itself, to my mind, is nothing more nor less than the instinct of growth, of permanence, of accumulating forces, of power; where the will to power is lacking, degeneration sets in. . . .

Christianity is called the religion of pity. — Pity is opposed to the tonic passions which enhance the energy of the feeling of life: its action is depressing. A man loses power when he pities. By means of pity the drain on strength which suffering itself already introduces into the world is multiplied a thousandfold. Through pity, suffering itself becomes infectious; in certain circumstances it may lead to a total loss of life and vital energy. . . .

On the whole, pity thwarts the law of development which is the law of selection. It preserves that which is ripe for death, it fights in favour of the disinherited and the condemned of life; thanks to the multitude of abortions of all kinds which it maintains in life, it lends life itself a sombre and questionable aspect. People have dared to all pity a virtue ( — in every noble culture it is considered as a weakness — ); people went still further, they exalted it to the virtue, the root and origin of all virtues. (6)

Nothing is more unhealthy in the midst of our unhealthy modernity, than Christian pity. To be doctors here, to be inexorable here, to wield the knife effectively here, — all this is our business, all this is our kind of love to our fellows. (7)

[I]t is to this miserable flattery of personal vanity that Christianity owes its triumph, — by means of this it lured all the bungled and the botched, all revolting and revolted people, all abortions, the whole of the refuse and offal of humanity, over to its side. . . . The poison of the doctrine of “equal rights for all” — has been dispensed with the greatest thoroughness by Christianity. Christianity, prompted by the most secret recesses of bad instincts, has waged a deadly war upon all feeling of reverence and distance between man and man. . . . And do not let us underestimate the fatal influence which, springing from Christianity, has insinuated itself even into politics! Nowadays no one has the courage of special rights, of rights of dominion. . . . Our politics are diseased with this lack of courage! — The aristocratic attitude of mind has been most thoroughly undermined by the lie of the equality of souls. . . . Christianity is the revolt of all things that crawl on their bellies against everything that is lofty: the gospel of the “lowly” lowers . . . (47-48)

[The Christian] is in his deepest instincts a rebel against everything privileged; he lives and struggles unremittingly for “equal rights”! (54)

Christianity is built upon the rancour of the sick; its instinct is directed against the sound, against health. Everything well-constituted, proud, high-spirited, and beautiful is offensive to its ears and eyes. (61)

Nietzsche became very popular among certain thinkers of the German National Socialist movement, but pointing that out may be rather unfair to him. It’s not at all clear that he would have favored Nazism, which arose after his death. Still, it’s not difficult to see why they found him appealing.

For Adolf Hitler’s take on the ethical lessons to be drawn from Darwinian evolution, see my 20 July 2018 column in the Deseret News, “Was Adolf Hitler religious?” And this fourteen-minute film on the Social Darwinist roots of the First World War might also be of interest..