(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

Okay. If I havn’t been clear enough yet, let me make it unmistakably plain now: I believe that, consonant with advice from their physicians (in some marginal cases), as many people as possible should seek out and receive one of the vaccines that have been or will yet be approved for use against the novel coronavirus. And I intend to beat the drum to that end.

I want to get the COVID-19 pandemic behind us, so that our economy can revive, theaters and restaurants can return to normal, religious congregations can meet, and — very importantly — the temples can fully reopen.

So don’t be surprised if I use this space fairly frequently over the next few weeks and months to exhort people to continue maintaining “social distance,” scrubbing their hands, and wearing masks, and to encourage them to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Anc please don’t become angry.

Here are a few relevant links for now, the first five of them from roughly ten to fifteen days ago:

“Moderna thinks its vaccine will protect against the coronavirus for at least a year”

“People are 52% immune after first COVID-19 vaccine dose, doctor says”

“More than 90,000 Americans could die of Covid-19 in next three weeks, CDC forecast shows”

For those who can access the Wall Street Journal:

“The face mask that could end the pandemic”

From Scientific American:

From the The Economist (and I hope that you can access it), a very helpful brief history of vaccination:

“The smallpox vaccine took decades to bear fruit”

Also from The Economist (and I hope that Utah and other health officials will read it):

But maybe we’ll just allow the pandemic to continue, destroying our economy and preventing the temples from opening up and giving it more time and more opportunities to mutate so that it can kill more people:

“Poll finds more Utahns willing to get COVID-19 vaccine, but is it enough?”

***

But let’s change the subject and the mood:

CNN: “A stream of nearly 500 stars in the Milky Way is actually a family”

Scientific American: “Why Do We Assume Extraterrestrials Might Want to Visit Us? The idea presumes we’re inherently fascinating, but that’s not necessarily the case”

From the current issue: Clara Moskowitz, “Cosmic Conundrum: The strangely small value of the cosmological constant is one of the biggest unsolved mysteries in physics,” Scientific American 324/2 (February 2021): 24-29:

Quantum theory and experiments with particle accelerators both suggest that the universe is filled with “vacuum energy” — which is most likely connected with the mysterious “dark energy” — that pushes outward on space itself. It’s the reason that the universe is expanding, and not only expanding but doing so at a faster and faster rate.

But quantum theory predicts an enormous amount of vacuum energy, enough to have ensured that no stars or galaxies ever formed. Clearly, then, the value of vacuum energy is much lower — roughly 120 orders of magnitude lower — than what was predicted. Accordingly, some scientists have labeled vacuum energy “the worst theoretical prediction in the history of physics.” Or, as Antonio Padilla, a physicist at the University of Nottingham has said, “It’s generally regarded as one of the most awkward, embarrassing, difficult problems in theoretical physics today.”

And it has ramifications. For example, vacuum energy is thought to be the main ingredient in the “cosmological constant,” a mathematical term that looms large in the equations of general relativity.

But the cosmological constant itself has a complex history. “It was what you could call a nonsolution to a nonproblem,” says Rafael Sorkin, of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Ontario, Canada.

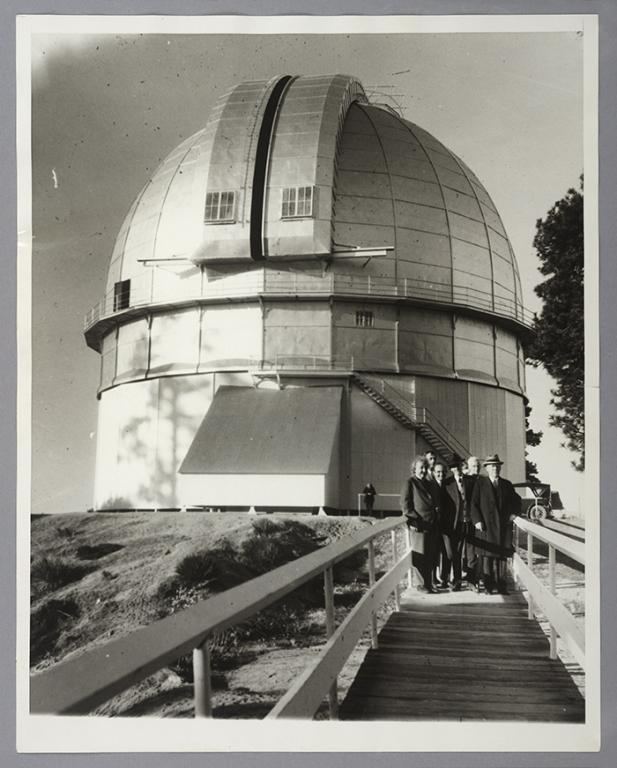

Albert Einstein invented in 1917 as a mathematical “kludge” in order to ensure that the field equations of his theory of general relativity didn’t entail an expanding universe. But then, in 1929, Edwin Hubble discovered astronomical evidence that, in fact, the universe is expanding. According to the late physicist George Gamow, Einstein eventually described the cosmological constant as “my biggest blunder” and removed it from his equations.

But then, in the late 1990s, two teams of astronomers were able to show that the expansion of the universe was speeding up, and they suggested that this acceleration was caused by “dark energy,” which, in turn, might have its source in the cosmological constant or “vacuum energy.”

But the value of the constant seemed to be wrong. And the question arose of exactly why it is precisely what it is. “Its value is very weird,” says Katherine Freese, a theoretical physicist at the University of Texas at Austin. “Even weirder than zero.”

The Nobel laureate Wolfgang Pauli noticed the problem already in the 1920s. By his calculations, vacuum energy should be so strong that the cosmos would have long since expanded to the point where light could not traverse the distances between of the objects within it. An observer on Earth, he calculated, should not be able to see even the Moon.

Of course, some physicists — notably the theoretical physicist Sabine Hosenfelder of Germany’s Frankfurt Institute for Advanced Studies — say that there’s no problem. It just is what it is, and that’s all.

But many scientists remain quite unsatisfied by such responses to the issue.

One of the most prominent — and, by some, most hated — solutions to the cosmological problem is called the anthropic principle. This line of thinking agrees that the cosmological constant in our universe has an unlikely value but explains it by saying we live in a multiverse. If ours is just one bubble in a cosmic sea, with different physical laws and constants in each, then there was bound to be one with this value. Most of the others would not lead to a universe with galaxies, stars, planets or life, so the fact that we find ourselves in one of the outliers is only to be expected. Because string theory requires a multiverse, string theorists tend to regard the cosmological constant problem as essentially solved by this reasoning. Other physicists, though, consider this philosophy a cop-out. “It’s giving up on the problem,” Sorkin says. (28)

I found it amusing to see Sorkin’s response, considering that philosophers and scientists who hypothesize that the life-permitting values of the various cosmic constants reflect some sort of “fine-tuning” are themselves often accused of “copping out” and of having “abandoned science.”

“We’ll keep trying,” [New York University’s Gregory] Gabadadze says of attempts to test cosmological constant hypotheses with experiments. . . . Despite the difficulty of the puzzle, he and other physicists still hope for a solution soon. Perhaps these efforts to understand the cosmological constant problem will reveal deeper truths about quantum physics and general relativity. Or maybe scientists will discover a simpler fix. And even while they’re seeking a solution that may never materialize, many physicists revel in the quest. (29)