***

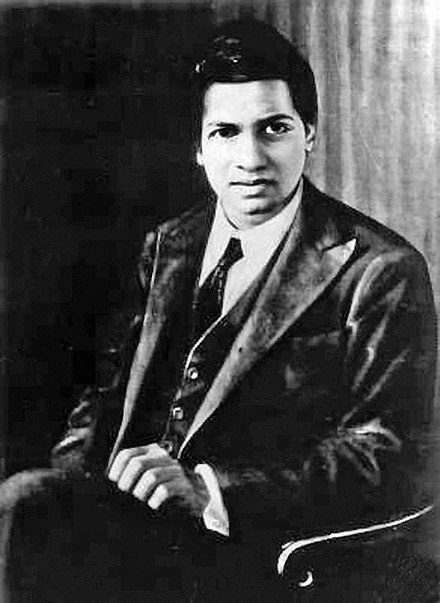

I first read about Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920) back when I was in eighth or ninth grade, probably either in James R. Newman’s four-volume The World of Mathematics or in E. T. Bell’s Men of Mathematics. (These are, incidentally, the books that initially sent me to the university as a mathematics major.) Ramanujan made an unforgettable impression on me.

He was largely self-taught, having received formal training in the kind of mathematics needed for an accountant or a clerk, but essentially none in pure mathematics. He did his own early original mathematical research in isolation for the simple reason that there was really nobody in his area capable of helping him. Nevertheless, he made significant contributions to such fields as number theory, the study of infinite series, mathematical analysis, and continued fractions, sometimes coming up with solutions to mathematical problems that, before him, had been considered insoluble. Although he tried to interest prominent academic mathematicians in his work, especially in distant England, he was unable to do so for a very long time. For one thing, his mode of presenting his findings didn’t fit accepted standards — which was, clearly, a result of his isolation. (He hadn’t been enculturated into the ways of professional mathematicians.) Accordingly, most of those whom he contacted dismissed him without serious attention. In 1913, however, he began a correspondence with the great English mathematician G. H. Hardy, at Cambridge University. Hardy almost instantly recognized that he was corresponding with a genius, and he arranged for Ramanujan to come to England and to the University. Ramanujan soon became one of the youngest people, and only the second native of India, to be named a Fellow of the prestigious Royal Society — a very big deal in a time of quite unashamed English and Western colonialism and racism — and he was the first Indian to be elected a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge.

Tragically, Ramanujan was compelled by poor health to return to India in 1919, and he died there in 1920 at the age of thirty-two. (The cause was probably complications of amoebic dysentery that he had contracted many years earlier; he had long told friends that he would not live to see the age of thirty-five.) Right up until shortly before his death, though, he was still generating new mathematical ideas and theorems, which he shared with Hardy via letters.

In the course of his sadly foreshortened life, Ramanujan compiled somewhere between 3,ooo and 4,000 distinct “results” — that range was suggested by G. H. Hardy; Berndt and associates came up with 3,254 (thanks to George Collins for the reference) — mostly in the form of identities and equations. Many of these were completely original to him. (Again, his lack of formal training and enculturation virtually guaranteed originality on his part.) Often, his results were unconventional, and mathematicians are still discovering fresh insights from his published works as as well as from his “lost journal,” which was recovered in 1976, and even his merest comments continue to yield a rich mathematical harvest. One can only imagine what he might have been able to accomplish had he lived a longer life. (For some reflections on that kind of question, please see my 2012 Deseret News column “Beethoven is a study in hope, healing.” Which was, by the way, not my choice for the column’s title.)

I found, and find, his story fascinating. Accordingly, when the film The Man Who Knew Infinity appeared in 2015, I was eager to see it. And I’m very glad that I did, because it alerted me to a very interesting element of Ramanujan’s life and mathematical work of which I had not previously been aware.

Finally, now, I’m reading the book from which the film was drawn: Robert Kanigel, The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius Ramanujan (New York and London: Washington Square Press, 1991). And here are some notes relating to that surprising element in Ramanujan’s biography and mathematical practice:

Ramanujan — his name means, literally, “younger brother of [the Hindu deity] Rama” — was born in what is today Tamil Nadu, India. His father was a clerk in a sari shop. His mother was a housewife who also served at a local Hindu temple. He didn’t do very well in school other than in mathematics, the only subject in which he had any real interest. In that area, however, he was recognized as a prodigy already at the age of eleven, soon exhausting the ability of all available teachers and tutors. When he was sixteen, he was given a copy G. S. Carr’s collection of 5,000 theorems, entitled A Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure and Applied Mathematics, which set his genius ablaze. Eventually, he himself obtained a position as a clerk.

He was exceptionally close to his mother, who was “fiercely devout” (20). He sang religious songs, participated in prayer meetings held at his house, grew up with the ancient stories of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, and was devoted to the family deity, the goddess Namagiri of Namakkal.

Ramanujan was a man who grew up praying to stone deities; who for most of his life took counsel from a family goddess, declaring it was she to whom his mathematical insights were owed; whose theorems would, at intellectually backbreaking cost, be proved true — yet leave mathematicians baffled that anyone could divine them in the first place. (4)

All the years he was growing up, he lived the life of a traditional Hindu Brahmin. He wore the kutumi, the topknot. His forehead was shaved. He was rigidly vegetarian. He frequented local temples. He participated in ceremonies and rituals at home. He traveled all over South India for pilgrimages. He regularly invoked the name of his family deity, the goddess Namagiri of Namakkal, and based his actions on what he took to be her wishes. He attributed to the gods his ability to navigate through the shoals of mathematical texts written in foreign languages. He could recite from the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other Hindu scriptures. (30-31)

It was goddess Namagiri, he would tell friends, to whom he owed his mathematical gifts. Namagiri would write the equations on his tongue. Namagiri would bestow mathematical insights in his dreams. (36)

To give a particularly, umm, vivid example: At one point,

in a dream, he saw a hand write across a screen made red by flowing blood, tracing out elliptic integrals. (66)

All of this raises a really important issue that pre-existed Ramanujan:

In the West, there was an old debate as to whether mathematical reality was made by mathematicians or, existing independently, was merely discovered by them. Ramanujan was squarely in the latter camp; for him, numbers and their mathematical relationships fairly threw off clues to how the universe fit together. Each new theorem was one more piece of the Infinite unfathomed. So he wasn’t being silly, or sly, or cute when later he told a friend, “An equation for me has no meaning unless it expresses a thought of God.” (66-67)

Ramanujan’s patron at Trinity College, Cambridge, G. H. Hardy, could scarcely have been more opposite. For one thing, whereas Ramanujan was short and squat, even fat, “with a full nose set onto a fleshy, lightly pock-marked face” (67), Hardy was physically beautiful. (That’s the word that’s often used for him, even into his fifties, rather than handsome.) As late as his thirties, Hardy was sometimes refused alcohol in restaurants and mistaken for an undergraduate. He was commonly described as “charming.” Yet he regarded himself as ugly. He allowed no mirrors in his rooms at Cambridge and, when traveling, would cover hotel room mirrors with towels. Like his sister Gertrude, to whom he was deeply devoted, he never married. Shy and very self-conscious, he loved cats, hated dogs, would not shake hands, and was an “almost pathological” player and fan of cricket, even weaving cricket metaphors into his mathematical papers — which often left his non-English colleagues completely baffled and lost.

Hardy and his sister Gertrude emerged from childhood “contemptuous of religion,” perhaps reacting against the deep religiosity of their parents and especially of their mother (117).

Hardy judged God, and found Him wanting. He was not just an atheist; he was a devout one. . . . God, it would be said of him, was his personal enemy. Yet his friends included clerics . . . (110)

Hardy was an atheist even as a boy. Once, as he and a clergyman walked in the fog, they saw a boy with a string and stick. The clergyman likened God’s presence to a kite, felt but unseen. In the fog, he told young Hardy, “you cannot see the kite flying, but you feel the pull on the string.” But in fog, Hardy thought, there is no wind and no kite can fly. Gertrude felt much the same. Once, as an old woman confined to a nursing home, she was asked her religious preference. She replied “Mohammedan,” bewailed the want of a mosque close by, even set about trying to locate a prayer rug to enhance the deception. (117)

Hardy spoke beautifully. He batted out sparking bons mots the way he did cricket balls from the popping crease — provoking, challenging, asserting. He was scrupulously honest, fastidious about giving others their due, once even admitted that the pro-God position in a debate had been better argued. (111)

For him, the whole spiritual realm was just so much bunkum. He knew — this was his faith — that wherever Ramanujan’s genius came from, there was something straightforward to explain it. (288)

Someone would later observe, though, that “Hardy’s deep reverence for mathematics and for all things of the mind was precisely of the same kind as impels other people to the worship of God; the only enigma about Hardy was that this never seemed to occur to him.” And at least for public consumption, it never did. Had Ramanujan scoured the British Isles, he could have found no one less sympathetic to his spiritual side, no one who, in this one realm, could appreciate him less. (288)

In fact, Hardy sought to downplay Ramanujan’s religious faith, suggesting that it wasn’t really very deep, and perhaps not even entirely sincere.

However, Ramanujan’s biographer, Robert Kanigel, will have none of this, suggesting instead that, if there was any disingenuousness on the Indian mathematician’s part, it was in not being forthright about his spirituality and his faith with the decidedly unsympathetic and unreceptive Hardy:

Ramanujan probably wasn’t long in England before Hardy let him know, perhaps without even realizing it, that invocations of Namagiri were not apt to be well received. Faced with a man once described as “an atheist evangelist,” and hardly wishing to provoke his benefactor and friend on what was such touchy ground, Ramanujan simply never revealed to him the richness and extent of his inner spiritual life.

And that was the problem: with Hardy, Ramanujan could not let his hair down — had to dissemble, could not be himself. There remained between the two men a great, unbridgeable gap. Even after working with him for several years, the conclusion is inescapable, Hardy never really knew Ramanujan — and thus could be no real buffer against the profound loneliness Ramanujan felt in England. (289)

But was G. H. Hardy really as hostile to religion and to theism as he seemed (and as he likely felt himself to be)? It’s tempting to wonder whether there might not have been, within the great mathematician, a spiritual core that, given different upbringing and altered circumstances and possibly a fresh perspective on theism — perhaps, I myself wonder as a Latter-day Saint theist, the circumstances now available to him in the world of spirits — might have made him more open to God. When Hardy died in 1947, one mourner spoke of his

profound conviction that the truths of mathematics described a bright and clear universe, exquisite and beautiful in its structure, in comparison with which the physical world was turbid and confused. It was this which made his friends . . . think that in his attitude to mathematics there was something which, being essentially spiritual, was near to religion. (7)

To be continued.

***

I finished my last class as a full-time member of the faculty of Brigham Young University last night at just a little before 5:00 PM. I’ll miss my interactions with students — which have already been blunted and made less satisfying by COVID-19 for the past year and more — and I’ll miss regular teaching, which I’ve always enjoyed. But it’s time, and there are other things that I need and want to do.

Almost immediately after the class was over, my wife told me that a couple we know wanted to take me out for dinner to celebrate my retirement. (Strictly speaking, I’m still working for the University through 30 June. My formal retirement will be effective on 1 July.) Fine, I thought. Having chosen a restaurant to go to — in itself, a thrilling novelty these days — I was caught totally by surprise when, entering the building, I saw a group of friends there, waiting for our arrival. I can’t believe that I was so naïve and clueless. I hadn’t so much as thought of such a thing. Right up to the very moment of seeing familiar faces.

***

If you haven’t yet gone to the Witnesses website and indicated that you want the film to come to a theater in your community, please do so. Please do so now. (See the band across the top of the site, where it says “Bring Witnesses to your city this summer.”) Don’t put it off. It’s important. It will be helpful to us even if you live in Utah, but especially if you live outside of Utah. Please do it while you’re on the computer right now.