***

Newly posted today on the website of the Interpreter Foundation:

***

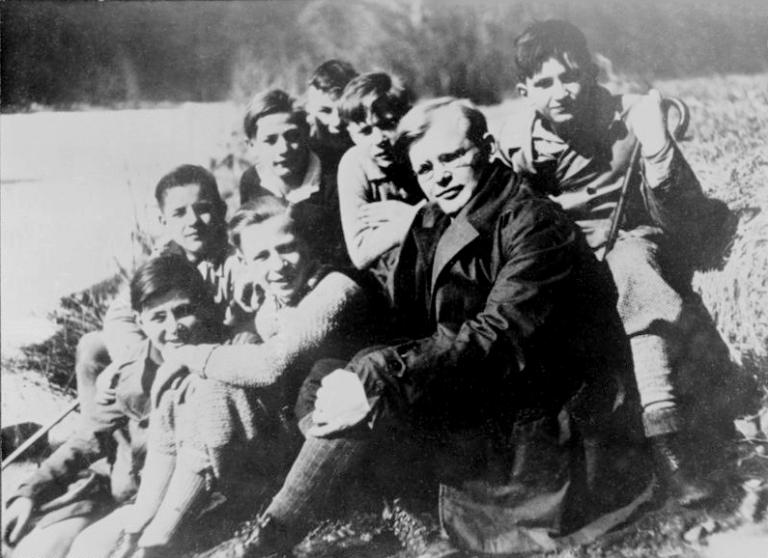

Since I’m already extracting them for my own notes, I’m going to share a few passages here (in my rough translations) that I think some of you might find of interest. They come from Christiane Tietz, Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Theologe im Widerstand (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2013), a book that I bought during a visit to the former Nazi concentration camp at Buchenwald, near Weimar, a few years back. (I had been delivering a paper at a conference hosted by the University of Erfurt, which is also not too far distant.) As the title suggests, the book is about the heroic Protestant theologian, pastor, and anti-Nazi martyr Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945), who had been imprisoned for a time at Buchenwald because of his role in the famous 20 July 1944 assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler that was carried out by Claus von Stauffenberg and his co-conspirators. (Sometimes not quite accurately called Unternehmen Walküre or “Operation Valkyrie,” this was the same plot that implicated Field Marshal Erwin Rommel and led to his arrest and forced suicide.) Dietrich Bonhoeffer was executed at Flossenbürg just twenty-one days before the death of Adolf Hitler.

In a letter written in English to the eminent American Protestant theologian Reinhold Niebuhr in 1939, Bonhoeffer reflected on the situation confronting Christians in his homeland:

The Christians in Germany will stand before the terrible alternative of either desiring the defeat of their nation, so that Christian civilization can survive or else desiring the victory of their nation, which will destroy our civilization. I know which of these I must choose, but I cannot make this choice . . . in safety. (88, translated into English from Christiane Tietz’s translation of the original English into German; I wonder how close I’ve come to the original)

A terrible choice, and he paid for his decision with his life. But, now, on to some other passages:

“It’s not self-evident for a Christian that he gets to live among Christians.” For, actually, “the Christian [belongs] not in the isolation of a cloistered life but in the midst of his enemies. That is where he has his assignment, his work.” (80, citing Gemeinsames Leben [which is, as I recall, typically rendered in English as Life in Community]

I think that Latter-day Saints and, indeed Christians and theists more generally, need to come to grips with the fact that we live in a society that no longer gives even lip-service to traditional religious beliefs or loyalties. When I was a boy, there was still a sort of cultural deference to a broadly Judeo-Christian civil religion. But no longer.

A Christian community takes its life from the intercession of its members for each other, or else it dies. No matter how many challenges he presents to me, I cannot any longer condemn or hate a brother for whom I pray. His appareance, which may have been alien and even unendurable to me, transforms itself in my intercessory prayer into the countenance of the brother for whom Christ died, into the countenance of a brother who has been blessed with grace. (82, citing Gemeinsames Leben)

It is in confession that the breakthrough to community occurs. Sin wants to be alone with each human individual. It removes him from community. The more solitary a person becomes, the more destructive the hold that sin will have over him, and the more deeply entangled he is in it, the more hopeless is the solitude. Sin wants to remain unrecognized. It avoids the light. In the darkness of the unexpressed it poisons the complete being of a person. (81, citing Gemeinsames Leben)

At the same time, Bonhoeffer emphasizes that “Whoever cannot be alone should beware of community.” and the proposition is also valid, in his view, when turned around:

Everyone, in and of himself, has profound depths and dangers. Whoever wants to have community without solitude falls into the emptiness of words and feelings. But whoever wants to have solitude without community perishes in the abyss of vanity, infatuation with himself, and despair. (82, citing Gemeinsames Leben)

I like this passage, which comes from Bonhoeffer himself (from Brautbriefe 38, one of the letters that he wrote from prison to his fiancée, Maria von Wedemeyer:

I fear that Christians who only dare to stand with one leg on the earth also stand with only one leg in heaven. (cited on 116)

I don’t like this one, which actually comes not from Bonhoeffer but, rather, from the author of the book, Christiane Tietz, who is a professor of systematic theology at the Universität Mainz, in Germany:

We can no longer join in certain of Bonhoeffer’s views today. Among those . . . are his conservative political sensibility [Politikverständnis] and his traditional image of the family. (131)

I’m not certain exactly what Dr. Tietz has in mind when she writes of a “traditionelles Familienbild,” but I’m reasonably confident that she would apply that description to my own views. And I certainly have a “conservative political sensibility.” I realize, of course, that my views are out of vogue. But I’m not sure that they’ve been refuted or that other views have been demonstrated to be superior. Time will tell whether current experiments — among other things, with issues of gender and sexuality — are actually sustainable, let alone beneficial for overall human flourishing. But I find myself wondering whether, despite the defeat of Hitler, Nazism, and the Third Reich, “Christian civilization” hasn’t been destroyed nonetheless.

The orientation toward Christ was always accompanied, in Bonhoeffer’s case, by the conviction that Christian community — that is, the church — is necessary for a Christian life. One cannot be a Christian on one’s own, but only together with others. This insight has not always been honored in Protestantism over recent decades. In fact, one has often heard, it is the particular mark of being an Evangelical Christian — as distinct from Catholic Christianity — that one can be faithful without the church. (132)

Posted from Richmond, Virginia