***

Last night, we watched a special piece from the CBS 60 Minutes program that was first broadcast on Sunday evening. It was entitled The Ritchie Boys. It focused on the former Camp Ritchie, Maryland, an elite military intelligence school during the Second World War, and on four very old survivors from among those who were trained there. All four of them, as it happened, were German refugee Jews, whose language skills and cultural background made them highly useful to the U.S. military.

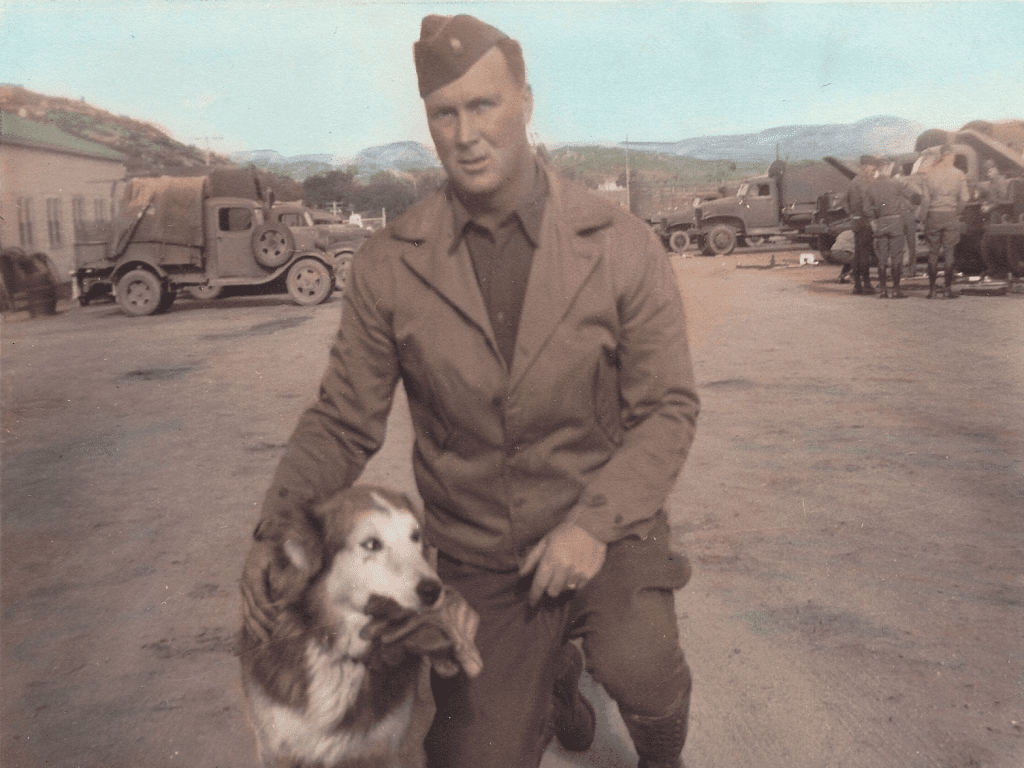

My Dad, too, was a “Ritchie Boy,” but he never made a big deal of it. He mentioned his having been at Camp Ritchie occasionally, but I never appreciated what a remarkable place it was until after he passed away. (My wife and I have visited it since; it’s no longer called “Camp Ritchie.”) I have so many questions that I would like to ask him now!

There were several things in the 60 Minutes program that helped me to make sense of bits and pieces of my father’s life. I know that he was involved in interrogating German prisoners of war. That was a Ritchie Boy specialty. I also know that, just as was mentioned for other Ritchie Boys in the 60 Minutes piece, he guided local people through the liberated camp at Mauthausen. They professed to have never suspected anything and to have known nothing at all about what was happening to the inmates there. Dad wasn’t persuaded. Some of them complained that the Mauthausen inmates whom the United States had liberated had stolen cabbages and other vegetables from their house gardens. The Army didn’t have food enough to feed all of the emaciated and starving captives or personnel enough to deal with them (and had found that, in some cases, if they fed them they killed them). So they gave them a bit of food and told them to go home if they could and to forage where they were able. Complaints from the locals about stolen produce didn’t gain a lot of sympathy from the American soldiers after they had seen the horrors of the extermination camp.

I also knew that my father had taken photographs of Mauthausen immediately after the liberation — terrible photographs, which I still possess — and that he had posted them in front of the then city hall in Linz, Austria, under the banner “Nazi Kultur.” He remembered hearing people passing by, gazing at his photos, and saying “Das habe ich nie gewusst!” (“I never knew that!”)

I had always wondered why he took so many photographs, and whether he had simply had free time to wander about, after liberation, snapping souvenir photos at his own initiative. I now see that posting such photos in prominent places was something that many “Ritchie Boys” did in areas near liberated Nazi death camps. It was part of the Army’s postwar effort at “de-Nazification.” And we still own his personal copy of the German Order of Battle, a large and detailed book-length list of German military units, commanders, weapons, and so forth. Another copy, belonging to one of the interviewees, was shown during the 60 Minutes program. The Ritchie Boys were expected to memorize it. Again, the artifact was much more significant than I had realized.

My father’s principal activity, though, was aerial photo reconnaissance interpretation, which was also mentioned in the CBS program as part of the Ritchie program. He did it while based at High Wycombe, roughly midway between London and Oxford, and then, arriving shortly after D-Day, on the European continent. He served, too, in some capacity for the OSS, the Office of Strategic Services, which was dissolved a month after the end of the war and which was eventually replaced, in a sense, by the Central Intelligence Agency. But he never told me much about his involvement with the OSS, except that one of the things that he was asked to do was to keep an eye out for Nazi or pro-German sympathies among the men of the Eleventh Armored Division. He was obliged to file weekly reports with somebody at OSS, but I’m not sure what they covered.

My Dad was not fluent in German, though he had more than a little bit of the language and was sent by the Army to study German for a time at the University of Chicago. I don’t remember much of what he said about that period, except for one story (which I’ll tell presently) and the fact that he walked every day by the bleachers of Stagg Field, where a major portion of the Manhattan Project was housed, and where Enrico Fermi achieved the first sustained man-made nuclear fission reaction. As I recall, Dad said that they could tell that something important was going on, but that it was impossible to see what it was. Now here’s the story:

At the beginning of each class, the instructor would summon the members of the class to attention by calling out “Meine Herren!” (literally, “My Lords!” or “My Masters!” but, really, just “Gentlemen!”). In the back of the room sat an Army officer who knew no German and wasn’t a student but whose task was, simply, to make sure that the men on his list showed up for class and didn’t play hooky. After a week or two and several repetitions of “Meine Herren!” he stood up rather angrily one day to demand “Where the hell is Monahan?” He heard the German Meine Herren as Monahan, and plainly assumed that there was some soldier named Monahan who wasn’t on his list but who was skipping class.

Although my father lacked native or even fluent German, he had been raised in a predominantly Scandinavian-immigrant community in North Dakota, born to a Danish-American father who had come over as a baby and to a Norwegian-born mother who had arrived in the United States at, I think, the age of eighteen. Accordingly, he knew some Norwegian and was comfortable with Scandinavian ways. I wonder whether that fact played a role in his selection for Camp Ritchie, along with his high IQ, whatever it was. (I recall his telling me that he was dispatched to Ritchie shortly after taking an Army IQ test.) Perhaps, under slightly different circumstances, he might have been assigned to Norway. As it was, he was eventually delegated to Patton’s Third Army.

The CBS program focused on German-born Jewish refugees among the Ritchie Boys. At least three of the four that they interviewed, all of them in their late nineties by the time of their interviews, had gone into more or less academic careers: One of them had served as the dean of the Culinary School of America. One had taught Romance languages and literature at both Yale and Princeton, and the third had attended an Ivy League school and then worked as a professor somewhere for several decades.

I can understand easily enough, I think, why Hugh Nibley was chosen for Camp Ritchie. (He, too, was a Ritchie Boy.) Hugh was manifestly a person of extraordinarily high intelligence. He already had his Ph.D. by 1938. And, having served a mission in Germany, he was fluent in the language. My Dad, though, grew up on an isolated North Dakota farm — after visiting there this past summer, I have a much better feeling for just how isolated it was! — and, constrained by the Depression and without any money, had only earned an associate’s degree from Pierce College in Los Angeles after a year or so at the North Dakota School of Forestry. Thereafter, he had to make his living as a construction worker and had done a stint with Roosevelt’s New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps. Then, during the year or so before Pearl Harbor, he had joined the Army, where he was assigned to, of all things, the horse cavalry — yes, the horse cavalry still existed at that point — patrolling the border between the United States and Mexico from a base located near El Centro, California. 60 Minutes described Camp Ritchie as a group of “intellectuals.” I begin to appreciate what a tribute to my father it was that, given his humble background, the Army deemed him worthy of a place among such talented and well-credentialed men.

How I miss him.