(Wikimedia Commons public domain image)

The following is basically a close paraphrase or a gloss (for my note-taking purposes) of “A Beginner’s Guide to the ‘Fine-Tuning’ Argument” by Max Baker-Hytch of the University of Oxford. As always with such notes, I make no claim of originality for what follows but share them because, while I’m taking notes for my own eventual use elsewhere, I think others might find them of potential interest. I do not claim entries on this blog as publications of mine:

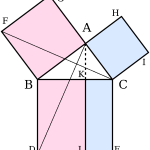

Over the past few decades — I, at least, certainly didn’t notice such claims when I was in high school — a number of physicists, philosophers, and others have begun to maintain that many aspects of the physical cosmos appear to be ‘fine-tuned’ for life, which is to say that various aspects of the basic structure of the universe and of the fundamental laws that govern it are balanced, as it were, on a knife’s edge. If any of them had been different by even the tiniest amount, the universe would have been incapable of giving rise to or sustaining life. In several cases, these “fine-tuned” features of the universe are such that, had they differed only very slightly from what they actually are, the universe would not have given rise to stars or even galaxies, let alone to complex and conscious creatures like . . . well, us.

Many specific examples of fine-tuning are available for consideration. I’ll mention two of them here, briefly:

It’s been estimated by physicists that, if the strength of gravity were to differ by just one part in 1060 — 1060 being a 1 followed by sixty (60) zeros, making one part in 1060 an almost inconceivably small number — there would be no stars and no galaxies. If it were a tiny bit stronger than it is, all matter would have collapsed back in on itself; it if were a tiny bit weaker, matter would have dispersed too quickly for galaxies or stars to be able to form.

Another example is what’s known as the “cosmological constant.” What is it? The cosmological constant is a number representing a factor that governs how fast space itself expands or contracts. Again, if it were a tiny bit too strong the universe would have collapsed back upon itself; if it were, by contrast, to be a tiny bit too weak, well, the universe would have expanded so quickly that galaxies and stars would be unable to form. It’s estimated that the chance of the cosmological constant having a value that would permit life is roughly 1 in 1053. (That’s a one followed by fifty-three zeros. So 1 over 1053 is, again, a very, very small number.)

Still, while many scientists and philosophers concur that the universe manifests “fine-tuning,” that agreement doesn’t extend to the meaning of the apparent fact. Some, for example, argue that it is an indication that a supremely intelligent and powerful being is responsible for our universe. (Overall, many scientists seem to me to be much more expressly friendly to theism than I recall from my youth.) Others, by contrast, contend that it is, simply, a “brute fact.” It just is, they argue, and no explanation for it is either necessary or possible.

One fairly witty way of denying that any explanation is needed for apparent “fine-tuning” runs roughly as follows:

If the universe hadn’t been fine-tuned for life, we wouldn’t be here to notice that fact. There’s no other kind of universe that we could have observed other than a fine-tuned universe! And, so, we shouldn’t be surprised to find ourselves in such a universe. If a puddle were somehow to exclaim in wonderment how the depression in the asphalt happens, as if by design, to fit his contours perfectly, we would laugh. Wouldn’t we?

The Canadian philosopher John Leslie has famously responded to this objection with a cute analogy that has become fairly popular: Suppose that you were condemned to be executed by firing squad. Fifty of the best marksmen in the land assemble, each of them armed with a rife and live ammunition. On command, they take aim and fire. To your amazement, though, after the crack of the rifles you’re still standing. You’re still alive, uninjured.

Once the immediate exhilaration and relief had passed, wouldn’t you be at least slightly curious about why you were still living, still unhit? Would you have much patience if someone were to approach you, saying, “Actually, you shouldn’t be surprised or curious. After all, if the firing squad hadn’t missed you wouldn’t be standing here to wonder about it.” On the understanding that every member of the firing squad intended to kill you, and that every single one of them was individually capable of doing so, your survival seems to have been extremely improbable and something for which you might understandably want an explanation. Leslie’s analogy is meant to represent the universe, of course: It appears to be true that the only kind of universe we could observe is a universe that is fine-tuned for our survival, but the existence of such a fine-tuned universe is very, very improbable on the hypothesis of sheer chance. Simple curiosity seems to suggest that we should be looking for another hypothesis to explain our being here.

What other hypotheses are on offer?

Some theists (and their fellow-travelers) have argued that the fine-tuning of the universe isn’t the result of mere chance but, instead, represents the deliberate choice or choices of an incredibly powerful rational mind, one to which the title God could reasonably be applied.

But there is another hypothesis that has been proposed, perhaps primarily if not solely to ward off the possible theistic implications of cosmic “fine-tuning” The hypothesis of a “multiverse” postulates that the universe that we know isn’t the only universe that exists. Instead, the hypothesis suggests, there is a vast ensemble of universes with differing initial conditions and different fundamental physical laws. Given enough such universes, so the hypothesis runs, one of them at least is bound to exhibit initial conditions and physical laws that enable the emergence of life.

So how well does the multiverse hypothesis actually work? Does it better account for “fine-tuning” than theism does? The debate continues to rage on this subject.

The theistic philosopher Robin Collins has devoted considerable attention to the question, and he suggests that the notion of a multiverse poses a serious dilemma: Either the multiverse is “unrestricted” (that is, it is essentially infinite and contains every logically possible universe) or it is “restricted” (which is to say that it contains only some of the logically possible universes).

If the latter, if the multiverse is restricted, then the question remains why the multiverse contains only this set of universes rather than some other set. But this choice simply kicks the “fine-tuning” can down the road a bit. The puzzle still remains as to why one of the finite number of universes available on the “restricted” view is apparently fine-tuned for life.

If, on the other hand, the multiverse is “unrestricted,” containing an infinite number of universes, this seems to pose potentially fatal problems for the very concept of scientific explanation itself. Why? Because, if the hypothesis of an unrestricted multiverse is true, then every logically possible event will actually happen somewhere in the boundless, infinitely capacious multiverse.

Suppose, Collins proposes, you roll a die a hundred times and, with every roll, it lands on six. If that were to happen in Las Vegas or Atlantic City, the casino proprietors and the observers standing around the table would all quite justifiably suspect that the die was rigged. In the unrestricted multiverse, though, everything that is logically possible actually does occur, and that includes a die legitimately landing on six a hundred times in a row. Or a thousand times in a row. Or a million times. Whenever something astounding happens, there won’t be any reason to ask “why.” So fifty sharpshooters missed you at very close range? No big deal. Everything that is logically possible — and there’s nothing strictly illogical about being missed by a fifty-member firing squad — actually happens in our unrestricted multiverse. So don’t worry. Be happy. Move along; there’s nothing to see here. And that would probably put an end to scientific investigation. No reasons are needed, so why should anybody seek them? Eat, drink, and be merry!

The fine-tuning argument does have at least one significant limitation from a theistic point of view, though: It doesn’t help us to choose between variant views of God. It certainly doesn’t establish the existence of the Judeo-Christian or Abrahamic God, the God of the Bible or the God of the Qur’an. It is consistent with most versions of theism, in the sense that it seems to provide grounds for belief in a supremely powerful and enormously intelligent designer. But no more. Thus, while it doesn’t establish any specific conception of deity, it can, potentially, serve as a component part of a broader cumulative argument for Christian theism.

Space Telescope

(NASA, ESA, Joel Kastner public domain image; processing by Alyssa Pagan)

Some of us — myself very much included — continue to bask in the glow of receiving the Kirtland Temple and other buildings and artifacts back into the custody of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and to contemplate their significance.

Here’s an idea to consider: “Utah Rivers Council encourages water conservation with subsidized rain barrels: The recycled-plastic barrels normally cost more than $150, but are available to residents of partnering municipalities for $55 and to all Utah residents for $83”

(Wikimedia Commons public domain photo)

The Book of Mormon in Context Lesson 12: “This Is the Way”: 2 Nephi 31-33

During the 25 February 2024 Come, Follow Me segment of the Interpreter Radio Show, Steve Densley, John Thompson, and special guest Kerry Muhlestein discussed Book of Mormon lesson 12, “This Is the Way,” on 2 Nephi 31-33.

A recording of their discussion has now been edited to remove commercial breaks and placed online for your listening pleasure at no charge. The other segments of the 25 February 2024 radio program can be accessed at https://interpreterfoundation.org/interpreter-radio-show-february-25-2024.

The Interpreter Radio Show can be heard on Sunday evenings each week from 7 to 9 PM (MDT), on K-TALK, AM 1640, or you can listen live on the Internet at ktalkmedia.com.

Editor’s Note: Four years ago, Jonn Claybaugh began writing the Study and Teaching Helps series of articles for Interpreter. We now have these wonderful and useful posts for all four years of Come, Follow Me lessons. Beginning this year we will be reposting these articles, with dates, lesson numbers, and titles updated for the current year’s lessons. Jonn has graciously agreed to write new study aids for those lessons that do not directly correspond to 2020 lessons.

I found this abomination in the Christopher Hitchens Memorial “How Religion Poisons Everything” File™, and feel obliged to inflict it upon you, as well: “How Do We Fix Poverty? ‘[We’ve] Got to Work Together,’ Humanitarian Services Director Says: Sharon Eubank participates in panel at the UN Commission on the Status of Women”