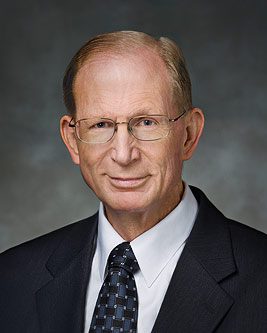

I first met Bruce when we were neighbors on the third floor of BYU’s Hinckley Hall during our freshman year at the University. His roommate was another very tall freshman, who went by the name of Clayton Christensen. Clayton himself has gone on to some rather notable accomplishments.

Bruce was a far more disciplined and focused student than I was. (So, for that matter, was Clayton.)

By reason of our living quarters, we were members of the same BYU student ward. However, while Bruce was called to serve as the Gospel Doctrine teacher I was given no substantial calling at all.

I was somewhat puzzled by this. I only divined the apparent reason at the end of the following academic year. I returned to the same ward (and the same bishop) for a second year before my mission—I had gone to BYU comparatively young—and was called as a priesthood quorum instructor. At the end of that second year, the bishop came into our quorum meeting and made some excesssively complimentary remarks about me as a teacher. “And to think,” he concluded, “that Brother Peterson was completely inactive only last year!”

Of course, I hadn’t been inactive at all. And sometimes Bruce had asked me to substitute for him in his Gospel Doctrine class.

We got along well. During the summer before his mission, I visited with him briefly at his parents’ home in Albuquerque.

Bruce was called to serve a mission in central Germany. Substantially later, I left for a mission to German-speaking Switzerland.

He eventually went off to Harvard for a doctorate in political science and international relations, with an emphasis on what was then called the Soviet Union.

Again somewhat later, I went to Jerusalem and then to Cairo for work in Arabic and Middle Eastern studies.

Our next significant contact was a moving one, for me at least.

One summer, my wife and I were headed from Egypt to California for the summer. We stopped off in Switzerland where, among other things, we attended a session in the temple at Zollikofen, near Bern. By this time, I had been shocked and somewhat discouraged to hear of the apostasies of a couple of bright undergraduate friends. Almost instantly upon leaving BYU, they had shed their Mormonism with no apparent anguish and had adopted lifestyles that were starkly incompatible with the standards of the Church.

So I was absolutely delighted when we ran into Bruce and Susan Porter there at the temple. (He was working in Munich, at the time, for Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty.) I immediately thought—and, even at this remove in time, I cannot help thinking—of Alma’s meeting with the sons of Mosiah after years of separation: “Alma did rejoice exceedingly to see his brethren; and what added more to his joy, they were still his brethren in the Lord” (Alma 17:2).

Bruce and I were in sporadic contact after that, until the time that, a few years after I had joined the faculty of Asian and Near Eastern Languages at BYU, the University’s Department of Political Science began trying to recruit him. (He was a research fellow at Harvard’s Olin Center for Strategic Studies by this point, having returned to Harvard in 1990.) We spoke several times about the possibility of his moving to Provo; he sought counsel and feedback from other (mutual) friends, too.

He ultimately came to BYU in 1993, I believe, where he was on track to have a very successful academic career.

He was an organized and productive scholar. He once told me that, when he first arrived at Harvard as a student, he noticed that many of his department’s doctoral students were spending more time in graduate school than they really needed to, and that he was determined to finish his degree and get on with his career. So he planned his coursework, worked efficiently, and finished relatively quickly. And, he told me, when his advisory committee said “Congratulations, Dr. Porter!” after his successful dissertation defense, he couldn’t help feeling himself just a bit of a fraud. Obtaining a Ph.D. had been easier than he thought it should have been. The general sense at Harvard, he judged, was that, if you were good enough to get into the program there in the first place, the powers-that-be figured that you probably wouldn’t embarrass them whatever they themselves added or didn’t add. So, because he realized that he could, he sailed right on through (relatively speaking). It was only in 1984, he said, after Cambridge University Press had published his first book (USSR in Third World Conflicts: Soviet Arms and Diplomacy in Local Wars 1945-1980) that he really felt worthy of the title Doctor. He went on to publish Red Armies in Crisis in the Significant Issues Series published by Georgetown’s Center for Strategic and International Studies (1992), as well as a personal favorite of mine, War and the Rise of the State (Simon and Schuster, 1994), prior to being called as a General Authority. (In 2007, Deseret Book published his LDS-oriented volume The King of Kings.)

Another comment about Harvard: Bruce spent a lot of time around Harvard’s “Sovietologists,” as they were then known. And he was amused by what many people outside of the University assumed about them. Time and again, while he was there, officials of the Reagan and first Bush administrations would come to campus and, in an effort to demonstrate their urbanity and sophistication by playing to what they assumed were the local elite academic attitudes, would try to distance themselves from the supposedly simple-minded anti-communism of those two Republican presidencies. On one occasion, a Reagan-era official apologized to his listeners at Harvard for Ronald Reagan’s characterization of the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.” One of the most prominent Soviet experts in the audience immediately demanded to know why the man was apologizing. The Soviet Union, this professor said, is evil, and it’s an empire. Hence, it’s an evil empire. What’s the problem, he wanted to know, with frankly calling it that? The administration official looked around with puzzlement, Bruce told me, blinking and probably wondering where on earth he was. Could this really be Harvard?

Bruce regarded the underlying problem as one of “reverse provincialism.” These visiting Reagan/Bush administration officials were insecure, and they desperately wanted to show that they weren’t provincial rubes. He sensed the same problem at BYU when he visited before deciding to join the faculty. People teaching about Communism and the Soviet Union, he thought, were so eager to imitate what they imagined to be the enlightened and tolerant attitudes at elite schools that they were actually considerably to the left of the relevant Harvard professors.

But Bruce didn’t stay very long at BYU. I was watching general conference in April 1995 when his name was read off as a new member of the Seventy. I was caught entirely by surprise. But then, when I saw him walking—unmistakably 6’7” tall—toward the seats at the front of the Tabernacle, I knew that it wasn’t some other Bruce Porter.

We spoke shortly thereafter. He himself had also been caught by surprise. He had assumed, when he was asked to come and meet President Hinckley at Church headquarters, that he might be called as a mission president. He was shocked at the call that actually did come. And, for a while thereafter, he looked around at the other men in his quorum—substantially older than he was, and usually with much more ecclesiastical experience under their belts—and wondered what he was doing there among their number.

But he was impressed. He told me, a few months after his call, about the strong personalities among his fellow members of the Seventy. There were, sometimes, spirited discussions. But, he said, then someone would cite a scriptural passage that seemed clearly to settle the issue at hand, and everyone would nod in assent. He was struck by the seriousness with which these men sought to discern the will of the Lord and to obey it.

I asked him, over the next few weeks, what sorts of reactions he was receiving from his non-LDS friends at Harvard and elsewhere. They were baffled, he told me. It was as if he’d suddenly announced that he was giving up academia and joining a Buddhist monastery. One friend at Harvard called him to suggest that he simply tell “Mr. Hinckley” that this was a very, very great honor, and that he greatly appreciated it. “Thank you, but No. I have several books that I want to write, and my schedule simply won’t permit me to accept.”

Another story from soon after his call: When he was called to the Seventy, he and his wife hadn’t been long in their Utah Valley home. His work as a General Authority would be in Salt Lake City or, when it wasn’t in Salt Lake City, it would be in some other place even more distant. So they decided to sell their house. One day, he was giving a tour of the home to some prospective buyer. The woman asked a prudent and reasonable question: Why, having been in the house such a short time, were they selling it? He replied that he needed to sell it because he had been called as a General Authority. She laughed. “No, really,” she said. “Why are you selling it?”

Elder Porter suffered for years from kidney disease, including a failed transplant attempt, and spent quite a bit of time (presumably for that reason) assigned in Salt Lake City, where he was the Church’s expert on international affairs and how such matters might impinge upon the work. Early on, though, before his kidney failure, he was sent to live in the area presidency headquartered in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, with a particular responsibility from there for Russia and the territories formerly under direct Russian control. It was an exhausting time. Some members of the Seventy had told him how much they had enjoyed their service in area presidencies. His area, though, covered seven time zones, and he was on the road at least once every few weeks, under conditions that were far below optimal. Many provincial cities of the old Soviet Union, he told me—even cities of several million people—lacked so much as a single decent hotel. And, by “decent,” he didn’t mean “posh.” He meant “heated.” He meant “not requiring its guests to step over drunks and puddles of urine in the entryways.” He recalled one evening when he and Elder Charles Didier stayed awake all night in their trench coats, sitting on a metal heating unit, fearing to fall asleep. (“99.9 percent of the ‘glamor’ of this position,” he told me, “comes during two weekends, one in April and one in October.”)

Elder Porter and I spoke and emailed quite a bit after his call to service as a General Authority. Occasionally, we met for lunch. He was significantly involved with a couple of committees at Church headquarters that also included me.

Once, my wife and I were unexpectedly stranded in Frankfurt en route to Istanbul. We were picking up our luggage for a night in an airport hotel when we saw Susan Porter there at the airport. She graciously invited us to dinner at their apartment in the suburbs. Elder Porter was, if I recall correctly, heading off on assignment early the following morning. They were very kind.

Over the years of his service in the Seventy, we had very serious conversations about issues of Church history, developments at BYU, and other such things. He was deeply interested in the defense of the faith. (One notable reflection of that interest was his contribution to a debate in First Things, a distinguished conservative journal of religion and public affairs: https://www.firstthings.com/article/2008/10/003-is-mormonism-christian.)

In the summer of 2014, to his great satisfaction, his kidney problem seemed under control and he was sent back over to supervise the work in Russia, stationed this time in Moscow itself as the area president. He was delighted to return to the focus of his earliest “ministry”—his word—as a General Authority. He was enormously busy, and he was happily getting his Russian back into good shape. We wrote back and forth, and, on rare occasions when our schedules allowed, met together at conference time. I last heard from him on 13 November 2016, while he was still serving as the area president there. He was extremely interested in something that Salt Lake City had asked me to do. I owed him a report on it, but I kept putting my report off because I’ve been under the weather for the past five or six weeks. I thought I would get to it shortly.

Elder Bruce D. Porter, my dear friend, for whom I had and have enormous respect, suddenly became gravely ill at the beginning of December. He died on Wednesday, 28 December 2016, in Salt Lake City. I will miss him greatly. I’ll miss his wise seriousness, his wit, his kind thoughtfulness, his utterly faithful devotion, and his calm personal support through some quite difficult times. And I’m confident that the leaders of the Church will miss him, too. He was quietly reliable, with penetrating insights and sound judgment. His death is a grievous loss. My wife and I are praying for Susan and her family.

Posted from Carlsbad, California